Design a simple high-voltage half-bridge switched mode

advertisement

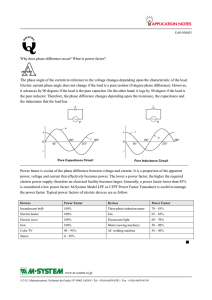

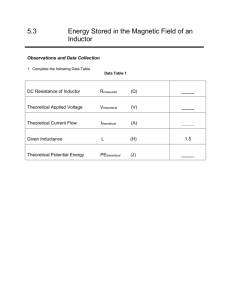

Design a simple high-voltage half-bridge switched mode power supply (SMPS) by Daniel Marks Draft document April 19, 2016 Building a mains-powered SMPS involves high voltages, mains voltages, and high currents that are lethal. You should not attempt to follow the design in this document unless you are thoroughly familiar with the dangers that working with mains voltage and high voltages entails. This document does not inform the reader of all such dangers, and so the reader should have previous experience at working with these risks before attempting to follow what is in this document. The author takes no responsibility for damage to life, property, or any injury, and the experimenter assumes all risk. The purpose of this document is to share and summarize the findings of the author in his experiences of constructing a SMPS. This document is for informational purposes only. The mention of any products or companies in this document are for informational purposes only and do not constitute an endorsement on part of the author. Introduction Modern MOSFETs (Metal oxide semiconductor field effect transistors) and IGBTs (Insulated gate bipolar transistors) are can conduct tens to hundreds of amperes of current and sustain source-drain (MOSFET) or emitter-collector (IGBT) voltages of hundreds to thousands of volts. Because of this, switched-mode power supplies (SMPS) can be built that convert kW of power from AC to DC, and with an efficient power factor. This opens up much opportunity to the hobbyists who wishes to exploit SMPS for experimentation, e.g. for high voltage experiments, Tesla coils, fusion devices, welding, induction heating, etc. This document summarizes some of the issues in constructing a simple SMPS based on a half-bridge topology, including the half-bridge, gate drive, and transformer construction. Most of this discussion also can be applied to building a full-bridge SMPS as well. Mains frequency transformers (50 ot 60 Hz) require very large cores to achieve sufficiently high inductance at this low frequency. The reactance of the secondary must be comparable or greater than that of the load, and as a result the core is typically a very large “E” shape with high magnetic permeability soft iron core laminations. A SMPS is able to use a much smaller transformer because the SMPS operates in the 10 to 300 kHz range of frequencies, and because the reactance of the windings scale with frequency, achieves a comparable reactance with a smaller core. As the eddy current and hysteresis losses of soft iron would be too great that the higher frequencies, typically ferrite core transformers are used, which are much less conductive and therefore do not conduct significant eddy currents, so that hysteresis loss is the major contributor to loss in the ferrite core. Because SMPS transformers are lighter and less expensive than mains frequency transformers, SMPS are replacing mains frequency transformers in most applications, especially those requiring high power. Unfortunately, this means that the mains frequency transformers that are currently used in high voltage experimentation, such as neon sign transformers (NST) and microwave oven transformers (MOT), are going to become increasingly difficult to find. This document was written to help the high voltage hobbyist transition to the same SMPS technology that is becoming dominant for other power electronics applications. The very popular Mazzilli/Royer flyback driver is used widely for this purpose, however, it has a problem directly using mains voltages, and has not scaled to over 1 kW of power. Furthermore, as LCD televisions are becoming dominant, the CRT flyback transformers typically used with the Mazzilli driver will become increasingly scarce as well. The half bridge configuration, which is already used in high current welders and solid state Tesla coils, is a good starting point for those who wish to work with a directly mains-powered high voltage source. Furthermore, winding a flyback transformer, while tedious, is not out of reach of the hobbyist, especially if large enough ferrite cores can be obtained. The high voltage SMPS in this document is unregulated, and is principally designed for charging capacitors for Tesla coils, Jacob's ladders, or other high voltage experimentation. It is current-limited by an inductor, not by duty cycle or frequency modulation like a conventional SMPS would be. It is designed to be as simple to construct as possible but be usable for the same sorts of applications that a MOT and NST would be used for. This means that the same sorts of safeguards that would ordinarily be on a commercial SMPS are not built into the SMPS in this document. There is a primary-side overcurrent detector, however, the secondary side current is limited by an inductor on the primary side, which must be designed to hold the current within limits even if the secondary windings are shorted. The voltage of the secondary can be very high if the secondary windings are open. The making and breaking of arcs is very hard on a power supply and can potentially cause voltage and current spikes that cause the transistors to exceed their safe operating limits, causing them to short out and be destroyed, even with snubbers and protection circuitry. Therefore, again, the experimenter is urged to pay attention to the potentially high voltages and currents involved in this SMPS, and to take precautions as any high voltage, non-current limited source would require. One shock can kill. The half bridge The half bridge is an attractive topology for building a switched-mode power supply. It uses a pair of transistors, one of which connects one side of the load to the positive supply, and the other the negative. The load is switched alternately between the maximum and minimum voltage by switching on one or the other transistor, but never both at the same time. The other side of the load is held at a nearly constant voltage that is nominally at half the supply voltage. This side is connected to a capacitor voltage divider between the positive and negative supply, and the capacitors also act to block DC current flow should the half bridge stop oscillating. The inductance of the transformer primary and any additional inductors and the capacitors for a series resonant LC circuit. The half bridge is typically operated at a frequency well above the resonance frequency of the LC circuit so that the inductance limits the current in the load. +V Load Gate drive signal Current limiting inductor +V Transformer Each transistor alternately switches one side of the load to +V and ground Split capacitors hold the other side of the load at a V/2 nominal voltage. Basic half-bridge circuit A full bridge is similar to a half-bridge, except that both sides of the load are connected to transistor pairs, and both sides of the load are alternately switched between the positive and negative supplies, with one side being connected to positive when the other is connected to negative, and vice versa. Because of this, a full bridge can deliver a voltage equal to the supply voltage across the load, while a half bridge only delivers a voltage equal to half the supply voltage. As a result, a full bridge can deliver double the power to the load for the same transistor current. The primary disadvantage of the full bridge is that it requires four transistors rather than two. The Royer or push-pull topology is popular because the Mazzili variant is able to self-oscillate, achieving zero-voltage-switching (ZVS) and therefore low switching losses. Its primary disadvantage is that if oscillation should cease, the load, which is a parallel LC resonator rather than a series circuit, presents a short-circuit. The series inductor with the load, which limits current while oscillating, is a short circuit when oscillation ceases. Therefore protection is required to shut the circuit down if a short circuit occurs and current levels are exceeded. Another disadvantage is that as each of the transistors delivers power through a separate winding, the voltage produced by the magnetization of the transformer works against the other transistor, so that the voltage stresses on each transistor is doubled. Furthermore, volt-second imbalance can occur if the two transistors are on for unequal times, saturating the core. Nevertheless, it has proved an attractive transformer driver for under 1 kW loads because it is easy to build and works reliably using transistors such as the IRFP260. A flyback converter, while easy to build, produces large stresses on the switching element, and is low efficiency. Furthermore, it magnetizes the transformer in only one direction, so that the total flux excursion is half of the Royer, half, or full bridge, so it does not deliver as much power per cycle. Therefore it is usually unsuitable for power supplies delivering more than 200 W because of the high power dissipation in the switching element. The two-switch forward converter has some advantages over the half-bridge, including no possibility of shoot-through, less voltage stress on the switches, resetting of the flux in the transformer each cycle if the duty cycle is less than 50%, and better recycling of the energy stored in the transformer. However, it delivers power on up to only one half of the cycle and magnetizes the core only one way rather than using the full flux deviation of the core, so that a more substantial transformer is required to deliver the same amount of power as a half bridge. Nevertheless, these are advantages that make it a viable alternative to a half bridge in many cases. Designing the half bridge and the transformer The essential features of the transformer can be designed using a few equations. Generally, a toroidal ferrite formed from two U-shaped pieces is used, made of a material such as Ferroxcube 3C85 or 3C90, Epcos N85, N95, or N96, or many others that will work. Surplus Sales of Nebraska (www.surplussales.com) often has inexpensive surplus ferrite cores for transformers, from which the author obtained ferrite cores. Information Unlimited (www.amazing1.com) also has prebuilt flyback transformers or ferrite cores. Television flyback transformers are also available from many sources including Goldmine Electronics (www.goldmine-elec.com) which may be useful to experiment with, however, the diodes in most television flyback transformers fail after conducting more than 300 W of power, as these were never intended for high power applications, and so the current limiting inductance should be designed for the lower power. The important feature is that the ferrite core must have a large enough cross-section for the desired power, and support switching frequencies up to 200 kHz. The toroid is split into two U-shaped halves, so that the secondary windings can be wound onto a bobbin, and then the toroid pieces slipped into the bobbin and joined into a magnetic circuit. Use a Ushaped toroid split into two halves with straight sections so that the bobbin that can be inserted between the two halves when ready. To start, you must know: · · · · · · · · The cross-sectional area A in m2 of the straight sections of the ferrite toroid that are slipped inside the bobbin. The length of the magnetic circuit Le which is the distance around the perimeter of the toroid. The saturation field Bsat of the ferrite (usually 0.2 Tesla is a good guess). The relative permeability me of the core material at the onset of saturation, usually 1500 is a good guess for many ferrite materials. The minimum working frequency of the switching converter f. The rectified voltage VR that is applied to the toroid. The desired secondary voltage VS. The desired power P. If using rectified mains without a voltage doubler , the rectified voltage VR can be determined from the mains voltage by VM. The factor coverts RMS mains voltage to the peak voltage, and the half factor accounts for the fact that a half-bridge divides the source voltage in half. If a voltage doubler is used on the mains voltage, then use . To estimate the minimum number of turns on the primary NP using Faraday's law before the saturation magnetization is reached: so that and volts per turn is . The number of secondary turns NS is given by the ratio The peak current to achieve the power P is given by To calculate the needed inductance of the primary LP (with the secondary open circuit) The inductance of the transformer may be reduced by increasing the gap size between the two halves. If on the other hand the inductance is too small to limit the current, additional primary windings need to be added, with a corresponding increase in the number of secondary turns. Alternatively, the frequency of oscillation may be increased to maintain the peak field in the core to within saturation limits. As the frequency is increased, the amount of power dissipated by the power transistors (IGBT/MOSFET) increases, and the hysteresis loss of the ferrite increases. Therefore this approach can be used only a limited amount. Many ferrite transformer materials are practically limited to 200 kHz operating frequency such as Ferroxcube 3C85 and 3C90. Older materials such as 3C85 also have higher hysteresis losses. The hysteresis losses heat up the ferrite core, and if the ferrite core reaches the Curie temperature, typically between 200ºC and 300ºC, the ferrite loses its ability to be magnetized, so the ferrite core must be maintained well below this temperature, usually below 120ºC. Materials such as Ferroxcube 3F3/3F4/3F5 can be used at a higher frequency, but cost significantly more. In general, the range of operating frequencies is between 20 to 100 kHz. Load voltage Load current Magnetic field Bsat VR IP 0 1/2f 1/f time -IP -Bsat -VR Idealized graph of the voltage, current, and magnetic field during a half bridge cycle The above calculations assume that there is perfect coupling between the primary and the secondary, that is, all of the flux lines in the primary winding also circulate through the secondary winding. However, often there is significant leakage of flux lines in a high voltage transformer. In a low voltage transformer, the primary and secondary coils are concentric so that there is the maximum coupling between the two. However, a high voltage coil requires strong galvanic isolation between the primary and the secondary wires so that there is no arcing between them, and the core itself which is slightly conductive. Therefore the primary and secondary are wound on opposite sides of the core with a significant gap between them. Unfortunately this results in significant flux leakage. The flux leakage results in leakage inductance. This is effectively an extra inductor in series with the primary coil of the transformer. Part of the voltage drop across the primary coil occurs at the leakage inductance, which limits the voltage and current at the part of the primary coil that actually couples field lines and therefore current to the secondary side of the coil. An ideal transformer without leakage inductance would have no primary coil inductance when its secondary is shorted, however, in a real transformer an inductance is still present if the secondary is shorted, which can be measured for example by using a LCR meter, as opposed to the total of leakage plus coupling inductance, which is measured with the secondary windings open circuit. Some leakage inductance can be helpful to limit the current, however, excessive leakage inductance prevents the desired current from being coupled to the secondary winding. The total inductance that limits the current when the secondary is shorted circuited is the leakage inductance of the transformer plus any additional inductance added in series with the transformer primary winding. More secondary windings need to be added to compensate for the flux loss due to the leakage inductance as well. The two halves of the transformer core are typically U-shaped as shown below. The gap is in between the two core halves. The gap width may be adjusted by inserting strips of electrical tape or other insulating, dimensionally stable tape between them. Increasing the gap width decreases the inductance of the transformer primary and therefore increases the current in the load. The halves should be clamped together tightly, but not so tightly that the brittle ferrite material cracks. Placing soft pads between the clamping surface and the ferrite helps avoid cracking. An estimate of the optimal gap size that prevents core saturation but minimizes the number of secondary turns needed is given by: with the magnetomotive force in ampere turns given by: and the effective permeability of the core adding the gap is Because of the skin effect, heavy duty wire should be used for the primary. Litz wire is ideal as it minimizes the skin effect, however, large gauge wire, multiple wound smaller strands of wire, or ribbon wire can suffice. Core halves Gap in core (not to scale) usually less than 1.0 mm thick. Primary wound on one side of core The dotted line is the length of the High voltage secondary wound on bobbin on the secondary side of the core magnetic circuit Le. Diagram of the two halves of the core and how they fit together. Winding the secondary, high-voltage side of the core must be done carefully as the voltage can arc between the wires. Typical windings for high voltage are designed in sections so that the stress of the high voltage is distributed between the sections, either laterally and/or radially, as shown in the following diagrams. First a plastic insulating tube is chosen for the bobbin, for example of PVC, ABS, or PMMA (plexiglas or lucite) materials. This tube should conform as closely as possible to the cross-section of the core, so that there is minimum flux leakage. Tubes can be purchased from hobby stores or Small Parts, Inc., or they can be designed and 3-D printed in ABS for the geometry needed. If water is used to wash support material away from the 3-D printed part, make sure that the part has been allowed to dry thoroughly before winding! The bobbin wall should be thick enough to prevent arcing of the voltage to the ferrite core, which may require wrapping extra dielectric layers around the bobbin. There are two common methods of winding high voltage transformers: side-by-side coils, and layered coils. Side-by-side coils can be used if there is more space available laterally then radially in the transformer core window. However, it uses space laterally for insulation between the sections. Layered coils can be used if there more space available radially than laterally. However, thick layers of insulation are required between the winding layers to prevent arcing between them. The two diagrams below show the two methods. Kinks in wires and points on solder joints should be avoided as these tend to be source of corona discharge which breaks down the dielectric. Depending on the voltage and frequency, the bobbin may need to be potted in epoxy or silicone and/or immersed in mineral oil or transformer oil when operating to prevent corona discharge from destroying the transformer. The benefit of mineral oil or transformer oil is that trapped air can be more easily excluded from the transformer, and that the dielectric is “self healing” to a degree. This is probably the easiest and best alternative available to the hobbyist. Beware of buying or recycling old transformer oil, as this may contain polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) which are toxic and an environmental hazard. An alternative is solid encapsulation. Paraffin has been used for solid encapsulation instead of oils, however, it melts at a rather low temperature which is a significant disadvantage. Clear two-part epoxy encapsulant may be purchased as wood varnish in quart/liter quantities, for example as Envirotex Lite which is available at craft stores, or in larger quantities online. Sand, fumed silica, quartz, or mica filler can be mixed with the epoxy when potting the transformer to help reduce the amount of epoxy needed. White or clear silicone caulk that is not acetic acid based (acetic acid based silicone smells like vinegar) can also be used as a dielectric, especially to seal around wires. Vacuum impregnation of the windings is needed for best results but often not available to the hobbyist. Vacuum impregnation of the windings removes trapped air that causes an effect called “partial discharges” where dielectric breakdown occurs at the dielectric-air interface. If vacuum impregnation is not available, agitation of the part and/or smoothing the polymer into the windings to push out the air can help avoid trapped air bubbles. Lower viscosity epoxy or silicone is often used to facilitiate better penetration of the windings with dielectric. To prevent the epoxy or silicone from curing inside the bobbin tube, an insert can be fashioned from expanded polystyrene (which can be obtained from packing materials) and placed into the tube while potting, which is easy to crumble away after the epoxy sets. If turns are layered on top of each other, the number of volts per turn should be calculated. Depending on the insulation used, there should be no more than approximately 100 to 150 V between any two turns in contact. If the core cross-section is large or the frequency is high, and therefore the number of volts per turn is large, only a few turns across can be used. For example, if 30 AWG wire is used, which is approximately 0.25 mm in diameter, and the transformer is 10 V/turn, then the permissible width of the section is (100V/10V)*0.25 mm=2.5 mm or approximately 1/10 inch. Corona is a discharge effect which slowly deteriorates the dielectric, and produces a purple glow in air. The amount of corona is determined by the ratio between the spacing between the wires and their diameter. For long, parallel wires, corona does not form if the ratio between the wire separation and the wire diameter is kept below 2.92. Therefore maintaining a close spacing of the wires prevents corona from forming. However, dielectric breakdown is still possible for a sufficiently high voltage. Current handling capability and diameters of copper wire for typical secondary wire gauges are: Gauge 24 AWG 26 AWG 28 AWG 30 AWG 32 AWG 34 AWG 36 AWG 38 AWG 40 AWG Current Capacity 0.577 A 0.361 A 0.226 A 0.142 A 0.091 A 0.056 A 0.035 A 0.023 A 0.014 A Diameter 0.51 mm 0.40 mm 0.32 mm 0.25 mm 0.20 mm 0.16 mm 0.13 mm 0.10 mm 0.078 mm Resistance 0.084 Ohms/m 0.133 Ohms/m 0.213 Ohms/m 0.338 Ohms/m 0.538 Ohms/m 0.856 Ohms/m 1.360 Ohms/m 2.163 Ohms/m 3.440 Ohms/m Skin Depth Frequency 68 kHz 107 kHz 170 kHz 270 kHz 430 kHz 690 kHz 1100 kHz 1750 kHz 2900 kHz Strong dielectric materials include polyethylene, polyester (Mylar), and PTFE sheets. PVC has a somewhat lower dielectric strength, but some grades are also useful. The high frequency AC breakdown field is typically far less than the DC breakdown field. The DC breakdown field measurement does not account for the stresses of the dielectric under the strain of repeated charging and discharging, especially with the direction of the electric field reversing each cycle. The DC breakdown field is as high as 500 V/mil or 20 kV/mm for polyethylene or PTFE, however, it is much reduced at tens to hundreds of kHz. A safety factor also must be included as sparks or other sudden discharges outside the transformer can cause temporary voltage spikes inside the secondary windings that can exceed the dielectric strength of the layer. Six mil, or 0.15 mm thick low density polyethylene sheets may be obtained in large rolls as undyed, translucent painters drop-cloth or tarp. However, these typically have small holes or defects so many layers should be used together. Thick sheets of PVC are available cheaply as shower pan liner, shower curtains, or mattress covers or bags. The ideal material is nonmetallized, undyed Mylar sheet, which is often used in transformers. A good safety factor should be to use an amount of insulation that produces three times the dielectric strength needed for DC breakdown. The sections must be narrow so that turns with different voltages greater than 100 volts in difference do not come in contact. This limits sections to 2 to 6 mm in width. Bobbin tube Insulating separators High voltage wires soldered onto magnet wire. Avoid sharp solder points! Notch cut in separator to allow wire to pass through separator on the surface of the tube Side-by-side coils high voltage bobbin. The bobbin is divided into sections by using insulating separators, and the wire wound onto each section before proceeding to the next, so that the voltage across any section is limited. A notch is cut into the section to allow the wire to cross to the next section. The position of the notch alternates between sides of the bobbin. A nylon or polyester thread can be tied over the wire in each section as it is completed, and at the bottom of each section as it is started, to ensure the wire stays in place and does not unravel or contact turns unintentionally. Alternatively, cyanoacrylate glue (super glue) may be used to glue the winds together which sets quickly, holds them in place during winding and prevents unraveling. The width of each section should be sufficient narrow so that turns with very different voltages do not come in contact with each other. It is very important not to run the wire from one section down the windings from the next section, otherwise arcing will occur between the wires of different potentials. The separator should be wide enough to allow the wire to descend from the top of the last winding to the bottom of the next without touching the windings of either the last or next section. High voltage wires soldered onto magnet wire on opposite sides of the tube Extra thick dielectric separator at outside Wound layer Thick dielectric separator Wire crosses from the end of the last layer to the beginning of the next layer through a short slit cut into the end of the separator Bobbin tube Thick dielectric separator Wound layer Layered high voltage bobbin. A coil of wire is wrapped around the bobbin tube for each layer. At the end of each layer, a thick layer of dielectric is placed, enough to stand at least three times the potential difference expected between the layers. The wire is then passed back along the bobbin tube to the beginning of the next layer, and another layer of dielectric is placed on the wire, and the pattern repeats for as many layers as needed. The layers may need to be several millimeters thick depending on the voltages between the layers. Two bobbins wound and wired in series to achieve a higher voltage. Primary coil Because the primary and secondary are in closer proximity, use sheets of insulation around the primary coil as well the secondary. Two bobbin or multibobbin separation. Multiple secondary bobbins can be placed on the core and used separately, or wired in series to achieve a higher voltage. The windings on the two bobbins must be in the same direction or the voltages will cancel, or the polarity of the connection on one of the bobbins should be reversed. Multiple bobbins can also reduce leakage inductance. Saturation of the transformer core When a constant voltage V is applied to the inductor for a time T, the current in the inductor is I=LVT. Because an inductor is really just a solenoid, we can calculate the magnetic field in the inductor from , where N is the number of turns of wire, I is the current in the wire, l is the length of the solenoid, and m is the magnetic permeability of the material inside the solenoid. Therefore put together: Therefore if a constant voltage is applied to the inductor, the current and the magnetic field rises in the inductor rises linearly in time. Eventually, the magnetic field reaches a point known as the saturation field. The permeability of soft magnetic materials depends on both the temperature and the applied magnetic field. When the magnetic field in the material becomes large enough, the magnetic permeability drops precipitously because the material can not be magnetized any further; it has reached the limit of the magnetic field strength it can produce. Because of this, the inductance of the solenoid, which depends on its permeability, drops as well until the magnetic field in the core falls below the saturation field. For most soft ferrite materials used in transformers, this saturation field is 0.3 T to 0.4 T, so it is important that this magnetic field strength is not exceeded. The effect of the sudden drop in the inductance of solenoid when saturation occurs is to allow a large surge of current to flow through the inductor, as the inductance which previously restricted the flow of current has been removed. This further drives the material into saturation, so that the current is likely to be ultimately limited by some other undesirable mechanism, e.g. blowing a fuse, burning a transistor, etc. As the magnetic field is concentrated when the cross-sectional area of the core is small, the cross sectional area of the transformer should be large enough to ensure that for the current required, the magnetic field does not approach or exceed the saturation magnetization. This is why larger transformer cores are needed for a higher power SMPS. Another way that transformers may be driven into saturation is called “volt second” imbalance. The polarity of the applied voltage is reversed periodically across the primary of the transformer. For one half of the cycle, if a voltage of V1 is applied for a time T1, this means a current of I=LT1V1 flows through the primary coil. If for the other half of the cycle, a voltage of V2 is applied for a time T2, the opposite current is forced through the coil, so that the net change in current for an entire cycle is I=LT1V1 -LT2V2. If the product T1V1 =T2V2 does not match, each cycle the current increases in the primary by the imbalance LT1V1 -LT2V2. Eventually, the current builds up to a level that produces a sufficiently strong field in the inductor to cause it to saturate. Therefore it is important to ensure that no direct current can build up in the primary coil. This is typically achieved by placing a DC blocking capacitor in series with the primary coil. It must be small enough so that the current does not accumulate for the transformer to enter saturation, but large enough so that the voltage drop is mostly across the inductor. In a half bridge, the series capacitor, which is on the order of 0.1 to 10 mF, serves to block the DC component of the current, preventing volt-section imbalance. However, the series capacitor does not completely eliminate the possibility of saturation, as detailed in the “staircase saturation” section 6.1 and 6.2 of Switchmode Power Supply Handbook by K. Billings and T. Morey, but their solution requires an active flux balancing technique which is beyond the scope of this design or document. Designing the current limiting inductor The current limiting inductor is needed if the leakage inductance of the transformer is insufficient to limit the current. Some leakage inductance in the transformer can be helpful to limit current, however, excessive leakage inductance limits current and does not allow sufficient power to be transmitted to the secondary. If the power supply is used to charge capacitors, for example in a Tesla coil primary circuit or a Marx generator, the capacitor appears as a short circuit when its begins to charge. Also, if there is arcing of the high voltage (whether intentionally or unintentionally), or a short circuit occurs, without a current limiting inductor there is the risk that the overcurrent circuit does not trip and the current rating of the MOSFETs/IGBTs are exceeded, destroying them. Therefore it is wise to include a current limiting inductor. If a ferrite core is used for the inductor, the minimum number of turns required to not saturate the core of the inductor again is given by where A is the cross-sectional area of the inductor core and Bsat is the saturation field. Generally, more turns than this are needed. The desired inductance needed to limit the current is given by where IL is the desired current limit, which normally would equal IP. If you do not know the inductance, in general it is wise to add many more winds than necessary to increase the inductance, and remove winds from the current limiting inductor as needed. Because the inductance is proportional to the square of the number of winds, as the number of winds becomes small, the inductance decreases sharply. Therefore when the number of winds decreases below 12 or so, remove them one at a time. Often inductor cores specify a quantity called AL, which is the inductance produced by 100 turns on the core. To figure out the inductance of the core in with an arbitrary number of turns N: Some iron powder cores may be unsuitable depending on the switching frequency used, so ferrites are generally preferred. Too high a density of winds may produce undesired interwinding capacitance. Another alternative is to use a large air-core solenoid. The benefit is that air does not saturate. For a flat, multiturn circular coil where r is the radius of the coil, N is the number of turns, and a is the radius of the wire. For a long, thin air solenoid where l is the length of the solenoid. An air solenoid can be formed by winding heavy gauge wire around a PVC pipe. Maximum current and power Given that the peak current is , make sure that your MOSFET/IGBTs are rated for this current. In particular the lower the mains voltage, the higher the peak current is and therefore the larger the power dissipation is in the transistors to achieve a particular power output. Furthermore, the power rating of the MOSFETs/IGBTs should not be exceeded, as even with a heat sink the package of the device has a limited thermal conductivity. MOSFETs are rated by an on resistance , usually from 0.050 W to 0.500 W so that each of the MOSFETs dissipate an amount of power neglecting switching power of . IGBTs have a collector-emitter forward voltage drop 2.5 V, so that the power dissipated is on the order of 1.5 V to . For larger amounts of current, IGBTs dissipate significantly less power than MOSFETs as the power scales linearly rather than as the square of current with MOSFETs. However, IGBTs switch more slowly than MOSFETs, especially when these are turning off. There is an additional power dissipiated during the switching from off to on and vice-versa, as the switch transitions from a low current, high voltage drop during its off state which dissipates little power, and a high current, low voltage drop state which dissipates relatively little power. During the transition, there is a significant voltage drop across the transistor as well as current, which is increasing or decreasing during the transition. This transition time takes on the order of nanoseconds to microseconds and depends on the inductance of the load connected to the transistor. A higher switching frequency results in a larger amount of the power being dissipated during switching which also must be factored into the heat dissipated by the transistors. A gate drive signal that switches between high and low voltages as quickly as possible is needed to ensure that the amount of time the transistor spends in its transition is minimized. As the capacitance of MOSFETs and IGBTs gates is significant, the gate driver may have to deliver hundreds of mA to many amperes briefly during a transition. A zero-voltage-switching (ZVS) gate driver times the switch transition so that the transistors are switched when the voltage across the transistor is zero, minimizing the switching power, but is more complicated to implement than the hard switching half bridge in this document. The open and short circuit reactive average power and peak current are given by Resonance and safe frequency operation At the resonance frequency, the tank circuit formed by the inductors and capacitors presents a zero ohm reactive load, shorting out the half bridge and destroying the transistors. While some designs operate near resonance and change the frequency to regulate the delivery of power to the load, for a simple half bridge it is safer to operate at a frequency far above the resonant frequency so that the current limiting inductor limits the current. The capacitance in series with the load should be high enough to lower the resonance frequency well below the operating frequency. The duty cycle of the half bridge may be varied and the frequency held constant to regulate the load, with the maximum power delivered at 50% duty cycle. If the total capacitance in series with the inductors is C, then the resonance frequencies to avoid are given by Half-bridge driver circuits There are two circuits included as half-bridge drivers. The first is based on the ubiquitous and inexpensive IR2153D half-bridge driver IC. This provides low and high side drive for the MOSFETs/IGBTs, and also oscillates at 50% duty cycle. Conveniently, it also has a built in zener diode to regulate the gate drive voltage, which can also be used (with low current < 10 mA) for other circuits. With the appropriate series resistor, the zener diode allows the IR2153D to be operated directly from mains, obviating the need for a separate power supply. The primary disadvantage it is that is not galvanically isolated from the half-bridge power supply. If the MOSFET/IGBT does short out or blow up, it takes the IR2153D and any other silicon (and sometimes other passive components) with it, often violently. This happens within milliseconds, so fuses or other circuit breakers do not react fast enough to prevent this failure. The second circuit is based on the UCC37321/UCC37322 gate driver ICs. These are used to drive a gate drive transformer, which galvanically isolates the half bridge from the driver circuit. The gate drive transformer is 1:1:1 and wound as a trifilar for best flux coupling, so that the drive pulse is transmitted undistorted. One winding is connected to the UCC37321 and UCC37322 gate drive outputs to alternate the voltage difference, and the other two windings are connected to each of the gates of the transistors. The two windings must be connected with opposite polarities to each of the gates of the transistors, so that they turn on alternately (rather than at the same time and produce shoot through!). A LM339 configured as an oscillator produces the timing signal, however, this is not 50% duty cycle. The output is then divided in half in frequency by a J-K flip flop to generate the 50% duty cycle signal. Each of these circuits is equipped with an overcurrent detector. The overcurrent detector uses a current sense transformer. This transformer consists of a primary winding which is simply the load wire wrapped one turn around the toroid, and a 50 to 100 turn secondary winding. A current sense load placed on the secondary winding is effectively reduced in impedance by the square of the turn ratio on the primary winding side. Therefore it allows a small sense load to be placed in series with the actual load, while maintaining galvanic isolation using the transformer. For example, a 10 W load on the secondary side with a 1:50 turn ratio appears to be 10 W/(50×50) or 0.004 W on the primary side. A full wave bridge rectifier is used to turn either a positive or negative current into a positive voltage on the secondary side. The voltage on the secondary is equal to the current in the primary times the secondary load resistance divided by the turns ratio, minus the diode drop losses. Therefore, minus the diode drop losses, for example 10 A of primary current with a 1:50 turn ratio and a 10 W sense load would produce 2 V on the sense load, which including the diode drop is near 1 V. There is a potentiometer to adjust the threshold at which the current limiting occurs. Note: the overcurrent detector does not detect shoot-through, only excessive load current. The overcurrent detector also doubles as a supply undervoltage detector, which shuts off oscillation if the low voltage DC supply voltage falls below 12 volts. The current limiting circuit consists of two comparators, the first of which compares the current sense voltage to a fixed level. The open collector comparator output suddenly discharges a capacitor when the current sense voltage threshold is exceeded. The voltage on this capacitor is sensed on a second comparator, which if the voltage on the capacitor falls below half the supply voltage, pulls the output of the second comparator low. This second comparator output is connected to an enable line on the gate drives of the IR2153D or UCC37321/UCC37322 to shut off the gates and therefore both of the transistors. A 1 MW resistor slowly recharges the capacitor and allows the oscillation to resume after approximately 1/10 s, so that the circuit does not need to be power cycled to resume operation. However, if the cause of the overcurrent condition is not remedied, the overcurrent condition will reoccur and the cycle of current shutdown and restart will continue. It is crucial to keep the wires short and fat between the collector and emitter of the IGBTs, the power buses, and the load. An increased inductance of these wires increase the transient voltage spikes that occur at the emitters and collectors. The snubber capacitor and resistor combination connected to the collector and emitter of each IGBT should also be as close as possible as well. There are additional capacitors between the positive and negative supply at the IGBTs to stabilize the voltage at the IGBT. Snubber capacitors should be polypropylene, MKP preferred. The capacitor and resistor may be replaced with several in parallel to reduce the inductance of the snubber. The IGBTs were inserted into screw terminal sockets to make them easier to replace. The two IGBTs were mounted on a 3-by-3 inch aluminum plate heatsink with a silicone pad between the IGBTs and the plate to isolate the collector from the heatsink. A fan is blown on the plate to cool it. Schottky diodes are shown in parallel with the gate drive resistors in these circuits. This is to reduce the time required to turn the transistor off. These diodes may not be necessary, but adding the diodes reduces the possibility of shoot through. The diodes should be rated for at least 40 V and 1 A. The circuits are shown with an optional voltage doubler. Two capacitors are needed if a voltage doubler is used, each rated for the mains voltage (plus a 2 times safety margin) of the supply. Without voltage doubling a single capacitor may be used, rated for the mains voltage (plus a 2 times safety margin) and the needed capacitance. A voltage doubler should not be used with a 230 V AC mains supply, unless the IGBTs are rated for 1200 V operation. The IR2153D is not designed to operate with a 1200 V half-bridge voltage, so a gate drive transformer should be used. It is often advantageous to use a voltage doubler with 120 V mains as it reduces the current required to be switched by the IGBTs. These circuits were designed to use a single +15 V DC, 2 A voltage supply as to minimize part count. The IR2153D circuit may be operated using its internal Zener voltage source as well. A switching power supply wall adapter may be used as long as its isolated. Other possibilities To mention some of the other potential refinements: · Using a pulse width modulated SMPS controller such as the TL494 to control the output voltage, or alternatively, design the circuit as a frequency-modulated LLC resonant converter. · Adding output overvoltage protection or supply undervoltage protection. · Compare the design to a two-switch forward converter. Example design spreadsheet: 120 VAC, no voltage doubling, 30 A maximum IGBT current, 1200 W Half Bridge Design Spreadsheet Units Mains Supply Voltage Mains Frequency Design Power Design Frequency 120 V RMS 60 Hz 1200 W 25000 Hz Transformer Core Sat. Field Cross-Sectional Area of Core Desired Secondary Voltage 0.2 Tesla 0.0008165306 m2 20000 VAC 2000 Gauss 8.16530625 cm2 Current Limit Core Sat. Field Cross-Sectional Area of Core 0.2 Tesla 0.0008165306 m2 2000 Gauss 8.16530625 cm2 Tank capacitor Number of Tank Capacitors 0.0000041 F 4 Half Bridge +/- Voltage Peak Current Supply Capacitance Number of Primary Turns Volts per Turn Primary Inductance Primary Inductance Check Primary Reactance Number of Secondary Turns 84.8528137424 V peak 28.2842712475 A peak 0.0008841941 F 5.1959357766 turns 16.3306125 V/turn 0.00003 H 0.00003 H 4.7123889804 Ohms 1224.6938074123 Number of Inductor Turns Minimum Inductance Inductance Check Reactance 5.1959357766 turns 0.00003 H 0.00003 H 4.7123889804 Ohms Total Tank Capacitance 0.0000164 F Resonance Frequency of Tank 5073.6742742157 Hz Resonance Frequency No Load 7175.2589696593 Hz Reactive Power No Load 600 VA Reactive Peak Current No Load 14.1421356237 A Reactive Power Short Circuit 1200 VA Reactive Peak Current Short Circui 28.2842712475 A 4.1 uF 884.1941282883 uF 30 uH 30 uH 30 uH 30 uH 16.4 uF Example design spreadsheet: 120 VAC, voltage doubling, 25 A maximum IGBT current, 1800 W Cross-Sectional Area of Core Mains Supply Voltage Mains Frequency Design Power Design Frequency Units 120 V RMS 60 Hz 1800 W 25000 Hz Transformer Core Sat. Field Cross-Sectional Area of Core Desired Secondary Voltage 0.2 Tesla 0.0008165306 m2 20000 VAC 2000 Gauss 8.16530625 cm2 Current Limit Core Sat. Field Cross-Sectional Area of Core 0.2 Tesla 0.0008165306 m2 2000 Gauss 8.16530625 cm2 Tank capacitor Number of Tank Capacitors Half Bridge +/- Voltage Peak Current Supply Capacitance Number of Primary Turns Volts per Turn Primary Inductance Primary Inductance Check Primary Reactance Number of Secondary Turns 0.0000041 F 4 169.7056274848 V peak 21.2132034356 A peak 0.0003315728 F 4.1 uF 331.5727981081 uF 10.3918715532 turns 16.3306125 V/turn 0.00008 H 0.00008 H 12.5663706144 Ohms 1224.6938074123 80 uH 80 uH Number of Inductor Turns Minimum 10.3918715532 turns Inductance 0.00008 H Inductance Check 0.00008 H Reactance 12.5663706144 Ohms 80 uH 80 uH Total Tank Capacitance 0.0000164 F Resonance Frequency of Tank 3106.9782732285 Hz Resonance Frequency No Load 4393.9308119983 Hz Reactive Power No Load 900 VA Reactive Peak Current No Load 10.6066017178 A Reactive Power Short Circuit 1800 VA Reactive Peak Current Short Circui 21.2132034356 A 16.4 uF Example design spreadsheet: 230 V AC, 50 Hz, no voltage doubling, 30 A maximum IGBT current, 2400 W Half Bridge Design Spreadsheet Mains Supply Voltage Mains Frequency Design Power Design Frequency Units 230 V RMS 50 Hz 2400 W 25000 Hz Transformer Core Sat. Field Cross-Sectional Area of Core Desired Secondary Voltage 0.2 Tesla 0.000816531 m2 20000 VAC 2000 Gauss 8.16530625 cm2 Current Limit Core Sat. Field Cross-Sectional Area of Core 0.2 Tesla 0.000816531 m2 2000 Gauss 8.16530625 cm2 Tank capacitor Number of Tank Capacitors 0.0000041 F 4 4.1 uF Half Bridge +/- Voltage Peak Current Supply Capacitance 162.6345597 V peak 29.51402217 A peak 0.000577651 F Number of Primary Turns Volts per Turn Primary Inductance Primary Inductance Check Primary Reactance Number of Secondary Turns 9.958876905 turns 16.3306125 V/turn 5.51042E-05 H 5.51042E-05 H 8.655742259 Ohms 1224.693807 55.10416667 uH 55.10416667 uH Number of Inductor Turns Inductance Inductance Check Reactance 9.958876905 turns 5.51042E-05 H 5.51042E-05 H 8.655742259 Ohms 55.10416667 uH 55.10416667 uH Total Tank Capacitance Resonance Frequency of Tank Resonance Frequency No Load Reactive Power No Load Reactive Peak Current No Load Reactive Power Short Circuit Reactive Peak Current Short Circuit 0.0000164 F 3743.613375 Hz 5294.268808 Hz 1200 VA 14.75701109 A 2400 VA 29.51402217 A 577.6512112 uF 16.4 uF IR2153D Half Bridge Driver + mains 250V, 25 A slow blow fuse Double pole, double throw switch Inrush current limiting resistor 5 W, 20 A e.g. EPCOS/TDK B57127P509M301 + Switch closed for voltage doubling Optional 20 A AC ammeter measures kW - IRV 15.6 V + - 100 kW 450 mF 25 V 1 100 kW 1 nF Optional 1 mA DC ammeter measures KVA 100 mF 25 V + - 14 IRV CST 15 W 2 W Metal Film 10 W 4W 3.3 nF 12 11 10 9 8 LM339 quad comparator 1 MW 1 2 3 4 5 100 W 1 mF 25 V 6 7 + - IRV 100 kW 1 mF 25 V Current limit set + - 50 mH nominal 3W 10 W CST The wires between RM/RMG, the load, and the collector and emitter of the IGBTs should be short (less than 8 cm) and fat (14 AWG or larger) to minimize inductance, The snubber capacitors/resistors should be located as close to the IGBT emitter and collector as possible as shown. IRV 10 kW IRV 0.1 mF 5× UF4007 1 A Fast Switching Diodes 13 RM 50 turns 26 AWG 3W 3W 3.3 nF/600 V PolyProp snubber 100 W 1k W Current limit inductor. Wind on toroidal ferrite core, 3 to 7 cm2 cross-sectional area. Number of turns depends on permeability of material and crosssection. Normally 7 to 20 turns. Start with a larger number of turns and decrease if unknown inductance. 3.3 nF/600 V PolyProp snubber ` 3 W 10 nF/1000 3 W V PolyProp snubber 1 turn 15 W 2 W Metal Film IRV 10 kW Current sense transformer. Wind on ferrite core, 0.25 cm2 cross-sectional area. Primary is one turn (wrap wire around toroid once). Secondary is 50 turns of 26 AWG + - 4 × 470 nF PolyProp 600 V 8 IR 2 2153D 7 Half 3 Bridge 6 driver 4 5 10 kW 22 kW 10 W 2× IGBT IKW40N65F5FKSA1 650 V, 40 A collector current, snubber diode integrated. Aluminum Heatsink (100 to 200 cm 2 area) and fan cooled. Drain is connected to case, so a thermally conductive, electrically insulating pad must be placed between transistor and heatsink if both transistors placed on the same heatsink! 1 or 2 × 3300 mF 200 to 400 V (depending if 600 V 30 A full- voltage doubling is used and if the mains is 120 VAC or 230 VAC) wave bridge rectifier RM RM 30 kW 4 W for 170 V, 60 kW 4 W for 330 V 170 to 330 V RM (rectified mains) AC input 12 V Zener e.g. 1N4742A 50 mH nominal primary 1000 turns 30 AWG Capacitors 4× 4.1 mF 600 V metallized polypropylene MKP Transformer. Wind on toroidal ferrite core, 3 to 7 cm 2 cross-sectional area. Must be gapped for stable operation (typical gap is 0.5 mm, can use plastic shim). Widening the gap decreases inductance and increases current. IR2153D half-bridge driver. Warning: entire circuit at mains voltage! Do not touch while energized! Electrocution may result! UCC37321/UCC37322 isolated gate drive half-bridge driver + mains 250V, 25 A slow blow fuse Double pole, double throw switch Inrush current limiting resistor 5 W, 20 A e.g. EPCOS/TDK B57127P509M301 + Switch closed for voltage doubling Optional 20 A AC ammeter measures kW - 1 STATE DISABLE + - 1 mF 25 V 2 7 UCC37321 6 3 ` 4 ` 5 1 8 1 mF 25 V Current limit inductor. Wind on toroidal ferrite core, 3 to 7 cm2 cross-sectional area. Number of turns depends on permeability of material and crosssection. Normally 7 to 20 turns. Start with a larger number of turns and decrease if unknown inductance. RMG 4 × 470 nF PolyProp RM 600 V 3.3 nF/600 V PolyProp snubber 1 mF 50 V ceramic 15 W 2 W Metal Film 3.3 W 4W RM 10 nF/1000 3 W V PolyProp 3 W snubber 1 turn 15 W 2 W Metal Film 50 turns 26 AWG 3W 3W CST 3W 10 W 3.3 nF/600 V PolyProp RMG snubber +15 V ` 4× UF4007 1 A Fast Switching Diodes ` 5 The wires between RM/RMG, the load, and the collector and emitter of the IGBTs should be short (less than 8 cm) and fat (14 AWG or larger) to minimize inductance, The snubber capacitors/resistors should be located as close to the IGBT emitter and collector as possible as shown. Gate drive transformer. Use a toroidal ferrite core minimum 0.5 cm 2 cross-sectional area. Wind using a trifliar pattern wiith 12 turns for the primary and the two secondaries. The gate-emitter connections of the two secondaries must be connected with opposite polarities to each IGBT as shown, so that the IGBTs turn on alternately. 50 mH nominal 50 mH nominal primary 1000 turns 30 AWG RMG RMG Capacitors 4× 4.1 mF 600 V metallized polypropylene MKP RMG 2 7 UCC37322 6 3 4 2× IGBT IKW40N65F5FKSA1 650 V, 40 A collector current, snubber diode integrated. Aluminum Heatsink (100 to 200 cm2 area) and fan cooled. Drain is connected to case, so a thermally conductive, electrically insulating pad must be placed between transistor and heatsink if both transistors placed on the same heatsink! Current sense transformer. Wind on ferrite core, 0.25 cm2 cross-sectional area. Primary is one turn (wrap wire around toroid once). Secondary is 50 turns of 26 AWG +15 V 8 + - + - 22 kW 10 W + - 1 or 2 × 3300 mF 200 to 400 V (depending if voltage doubling is used and if the mains is 120 VAC or 230 VAC) 600 V 30 A fullwave bridge rectifier +15 V 100 mF 25 V 170 to 330 V RM (rectified mains) AC input Transformer. Wind on toroidal ferrite core, 3 to 7 cm2 crosssectional area. Must be gapped for stable operation (typical gap is 0.5 mm, can use plastic shim). Widening the gap decreases inductance and increases current. UCC37321/UCC37322 half-bridge driver switch section Warning: parts of the circuit are at mains voltage! Risk of electrocution! NOTE: the drive circuit and the mains are galvanically isolated by the gate drive and current sense transformers. DO NOT tie the grounds together of these circuits! +15 V 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 Frequency divider to balance on/off time CD4027 JK flip flop 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 STATE +15 V +15 V +15 V 10 kW Schmitt trigger relaxation oscillator 50 kW 100 kW 100 kW 100 kW 100 kW 10 kW Optional 1 mA DC ammeter measures KVA +15 V +15 V 470 pF 10 kW 10 kW DISABLE 1k W 14 13 12 1 2 3 +15 V CST 10 W 4W 3.3 nF 1 MW 10 9 8 5 6 7 12 V Zener e.g. 1N4742A LM339 4 +15 V +15 V 100 W 0.1 mF 5× UF4007 1 A Fast Switching Diodes 11 1 mF 25 V + - 100 kW + 1 mF 25 V Current limit set Oscillator and overcurrent detector. Warning: parts of the circuit are at mains voltage! Risk of electrocution! Bibliography Textbooks: K. Billings and T. Morey, “Switchmode power supply handbook,” McGraw-Hill, New York , 2011. M. H. Rashid, Ed., “Power Electronics Handbook Third Edition,” Elsevier, Amsterdam 2011. B. B. Babani, “Coil Design and Construction,” Bernards, Manchester UK, 1960. M. Abdel-Salam, H. Anis, A. El-Morshedy, and R. Radwan, “High Voltage Engineering Theory and Practice,” Marcel Dekker, New York 2000. F. W. Peek, Jr., “Dielectric Phenomena in High Voltage Engineering,” McGraw-Hill, New York, 1920. Articles: N. Sanajit and A. Jangwanitlert, "A series-resonant half-bridge inverter for induction-iron appliances," Power Electronics and Drive Systems (PEDS), 2011 IEEE Ninth International Conference on, Singapore, 2011, pp. 46-50. Y. B. Shukla and S. K. Joshi, “Induction Heating System Using Self Oscillating Driver,” Journal of Electrical Engineering retrieved from http://www.jee.ro/covers/art.php? issue=WB1286956339W4cb56533d02a9 . T. Mitsui and G. Van Schaick, “Ferrite power material for high frequency applications,” Powertechnics Magazine, Feb. 1991. Application notes: L. Wuldart, “Topologies for switched mode power supplies,” ST Microelectronics application note AN513/0393 retrieved from http://www.st.com/web/en/resource/technical/document/application_note/CD00003910.pdf . M. Kamil, “Switch Mode Power Supply (SMPS) Topologies Part I,” Microchip application note AN1114 retrieved from http://ww1.microchip.com/downloads/en/AppNotes/01114A.pdf . A. Bersani, “Switch Mode Power Supply (SMPS) Topologies Part II,” Microchip application note AN12705 retrieved from http://ww1.microchip.com/downloads/en/AppNotes/01207A.pdf . H. Ding, “Design of a Resonant Half-Bridge converter using IRS2795(1,2) Control IC,” International Rectifier application note AN-1160 retrieved from http://www.infineon.com/dgdl/an-1160.pdf . T. Sutto, “2 Switch Forward-Current Mode Converter,” ON Semiconductor application note AN8373/D retrieved from http://www.onsemi.com/pub_link/Collateral/AND8373-D.PDF . R. Severns, “Design of snubbers for power circuits,” EE 456 handout course material, Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology retrieved from https://www.rosehulman.edu/~herniter/NAU_Classes/EE456/handouts/Design%20of%20Snubbers%20for%20Power %20Circuits.pdf . Ridley Engineering, “Flyback Transformer Primary Winding Structures,” Ridley Engineering Design Center, Article 53. retrieved from http://ridleyengineering.com/index.php/dc1/87-53-flybacktransformer-primary-winding-structures.html . Schneider Electric, “Solid-Cast Versus Resin-Encapsulated Transformers,” Data Bulletin 7300DB0402, retrieved from http://static.schneider-electric.us/docs/Electrical%20Distribution/Medium %20Voltage%20Transformers/General%20Documents/7300DB0402.pdf . Texas Instruments, “Magnetics Design 2 – Magnetic Core Characteristics,” SLUP124 retrieved from http://www.ti.com/lit/ml/slup124/slup124.pdf . Texas Instruments, “Magnetics Design 4 – Power Transformer Design,” SLUP126 retrieved from http://www.ti.com/lit/ml/slup126/slup126.pdf . Texas Instruments, “Magnetics Design 5 – Inductor and Flyback,” SLUP127 retrieved from https://www.ti.com/lit/ml/slup127/slup127.pdf . “A single plate induction cooker with the ST7FLITE09Y0,” ST Microelectronics application note AN2383 retrieved from http://www.st.com/st-webui/static/active/en/resource/technical/document/application_note/CD00115561.pdf . “An introduction to LLC resonant half-bridger converter,” ST microelectronics application note AN2644 retrieved from http://www.st.com/web/en/resource/technical/document/application_note/CD00174208.pdf . “Half-Bridge LLC Resonant Converter Design using FSFR-Series Fairchild Power Switch,” Fairchild Semiconductor application note AN-4151, retrieved from https://www.fairchildsemi.com/applicationnotes/AN/AN-4151.pdf . S. Abdel-Rahman, “Resonant LLC Converter: Operation and Design,” Infineon Application Note AN 2012-09, retrieved from http://www.infineon.com/dgdl/Application_Note_Resonant+LLC+Converter+Operation+and+Design_ Infineon.pdf?fileId=db3a30433a047ba0013a4a60e3be64a1 . R. Clark, “Air gapped magnetic cores,” retrieved from: http://info.ee.surrey.ac.uk/Workshop/advice/coils/gap/ . Schematics and on-line projects: S. Ward, “DRSSTC with OCD, Rev 192 2/11/05,” retrieved from http://www.stevehv.4hv.org/DRSSTC3/DRSSTC-OCDsch.JPG . S. Ward, “The Mini SSTC,” retrievd from http://www.stevehv.4hv.org/SSTC5.htm . J. Kraidin, “MOSFET induction heater,” retrieved from http://www.mindchallenger.com/inductionheater/ “IGBT halfbridge 20-200 kHz with overload protection,” retrieved from http://danyk.cz/igbt_3_en.html. R. Hartwell, “A KW Switch Mode Regulated High Voltage Power Supply,” retrieved from http://w5jgv.com/hv-ps1/ . Data Sheets: “LM139/LM239/LM339/LM2901/LM3302 Low Power Low Offset Voltage Quad Comparators,” National Semiconductor March 2004. “L6565 Quasi-Resonant SMPS Controller,” ST Microelectronics January 2003. “IR2153(D)(S)&(PbF) self-oscillating half-bridge driver,” International Rectifier, data sheet no PD60062. “UCC2732x/UCC3732x Single 9-A High-Speed Low-Side Mosfet Driver With Enable,” retrieved from http://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/ucc37321.pdf . “TL494 Pulse-Width-Modulation Control Circuits,” retrieved from http://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/tl494.pdf .