Macroelectronics: Perspectives on Technology and Applications

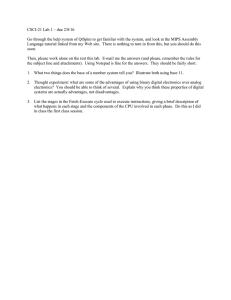

advertisement