Locked and Loaded: Taking Aim at the Growing Use of the American

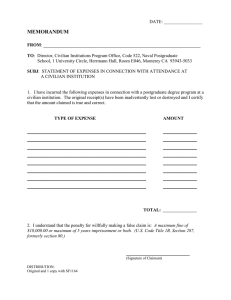

advertisement