Figure 6-2 - Worcester Polytechnic Institute

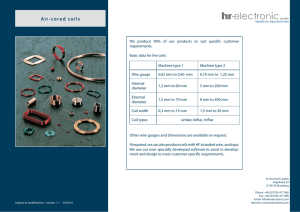

advertisement