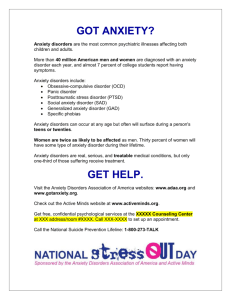

July 2006, Vol 51, Supplement 2

advertisement