New method for measuring low NO concentrations using laser

advertisement

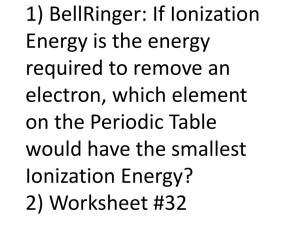

New method for measuring low NO concentrations using laser induced two photon ionization Shan-Hu Lee, Jun Hirokawa, Yoshizumi Kajii, and Hajime Akimotoa) Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology, The University of Tokyo, Komaba 4-6-1, Meguro, Tokyo 153, Japan ~Received 28 January 1997; accepted for publication 27 April 1997! A new method based on laser induced two photon ionization was developed for detection of low levels of NO concentration in the troposphere. A frequency-doubled pulsed dye laser operating at near 226 nm was used to photoionize NO by a (111) resonance enhanced two photon ionization via its A 2 S←X 2 P(0,0) band. NO ions are detected by an electron multiplier. Air gas samples are injected through a pulsed nozzle into a vacuum chamber. Cooling of rovibrational levels during the expansion process allows better selectivity for NO detection from other nitrocompounds. Measurement conditions were optimized as a function of X/D for the nozzle ~X is the distance from the nozzle orifice to the ionization area, and D is the diameter of the nozzle orifice!, laser power, and electron multiplier voltage. For the first time, selectivities for NO measurement, which were obtained from ion intensity ratios of NO and other nitrocompounds such as NO2 at the same concentrations, are discussed. A selectivity of 45 for NO vs NO2 was obtained using a 44 mJ pulse energy and an X/D of 120 for the nozzle. The current detection limit determined for NO was 16 pptv with an integration time of 1 min and a pulse energy of 44 mJ. © 1997 American Institute of Physics. @S0034-6748~97!04807-7# I. INTRODUCTION NO plays an important role in atmospheric chemistry, mainly in the chemistry of ozone. In the troposphere, in particular, the photochemical production of ozone critically depends on the concentration of NO.1 NO is also one of the key species in the formation of HNO3 which is a major component in the acidic precipitation. It is therefore necessary to measure low NO concentrations in order to confirm photochemical theories in the troposphere and to correctly estimate the increase of tropospheric oxidants directly contributed by anthropogenic influences. Intensive research has been conducted to develop the technology for measuring low NO concentrations.2,3 Among these, the most common method of NO detection is based on the chemiluminescent reaction with ozone (CL–O3); 4–7 O31NO→NO* This reaction produces electroni2 1O2. cally excited NO* 2 with an emission intensity proportional to the initial concentration of NO. Another method to detect NO is two photon laser induced fluorescence ~TP-LIF!.8,9 In this method, a 226 nm and a 1.1 mm laser beam were used to sequentially excite the rotationally resolved transition in the D 2 S←A 2 S and A 2 S←X 2 P manifolds, and the fluorescence resulting from the D 2 S→X 2 P transition was detected. Since the fluorescence occurs near 190 nm, a wavelength region free from laser generated background noise, signal-limited ~SL! measurement conditions in NO determination were obtained. Both measurement methods have achieved a detection limit in sub-pptv levels. Other methods include long path absorption and differential optical absorption which determined the relatively higher NO concentrations in urban pollution air.10–12 a! Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; Electronic mail: akimoto@atmchem.rcast.u-tokyo.ac.jp Rev. Sci. Instrum. 68 (7), July 1997 In this work, a new method for measuring low NO concentrations was studied by using laser induced two photon ionization, which is different from above methods, with the purpose of measuring tropospheric NO. A frequencydoubled pulsed dye laser operating near 226 nm was used to photoionize NO by (111) resonance enhanced two phonon multiphonon ionization ~TP-MPI! via its A 2 S←X 2 P(0,0) band. The general concept of ionization spectroscopy is well established.13–16 The ionization method possesses significant advantages over the LIF method in detection efficiency.17–19 In the ionization method, close to 100% of the ions can be collected, while in LIF the detection efficiencies are about 1024 due to the isotropical emission of photons. In addition, collisional quenching and reactions of electronically excited NO with other gases decrease the detection efficiency in LIF. Laser photoionization spectroscopy has been proposed as a method for detecting atmospheric pollutants like aniline, chlorinated ethylene, nitrobenzene, and dimethyl sulfide in ppmv or ppbv levels and is summarized well by Simeonsson et al.17 However, little data pertaining to the quantitative determination of low concentration of NO in the atmosphere are available. Simeonsson et al.17 and Lemier et al.18 have attempted to use this ionization system to develop a detection method for the measurement of NO and also of a number of NO2-containing nitrocompounds ~i.e., NO2, HNO3, nitromethane, DMNA, nitrobenzene, TNT, and RDX! using photofragmentation/photoionization processes. An ArF laser operating at 193 nm was used to fragment the target nitrocompounds and the resultant NO was again photoionized via its D 2 S←X 2 P(0,0) band; for NO detection, NO was directly photoionized. They have also used a 226 nm dye laser for both the fragmentation and ionization via the A 2 S←X 2 P(0,0) band of NO. Using the molecular beam ~MB! technique and time of flight mass spectroscopy ~TOFMS! a better detection limit of 8 ppbv was obtained using the 0034-6748/97/68(7)/2891/7/$10.00 © 1997 American Institute of Physics 2891 Downloaded¬17¬Dec¬2002¬to¬130.253.240.238.¬Redistribution¬subject¬to¬AIP¬license¬or¬copyright,¬see¬http://ojps.aip.org/rsio/rsicr.jsp 226 nm laser with an integration time of 10 s compared to 1.2 ppmv using the 193 nm laser, in spite of the lower laser energy ~100 mJ at 226 nm and 1–1.5 mJ at 193 nm!. This result is apparently due to the fact that the 193 nm excitation is resonant with the transition from weakly populated rotational states in the vibrational ground state in the A←X band of NO. They have further improved the detection limit to 1 ppbv for NO determination at 226 nm with a simplified detection apparatus by using a pair of miniature electrodes for ion detection, since the absolute molecular number detected was enhanced over the molecular beam technique. They suggested that exclusive NO ion production at 226 nm made mass detection by the time of flight mass spectrometer unnecessary for NO ion detection. By using (211) photon ionization of NO via its C 2 P( v 50) state, Guizard et al. have measured NO concentrations in laboratory study.19 The purpose of the present study is to focus on the selective detection of NO with a high sensitivity by minimizing the spectral interference from other nitrogen oxides, particularly NO2, as opposed to focusing on the nonselective detection of all nitrocompounds by using the same photodissociation/ photoionization process reported by Someosson et al. In order to improve the selectivity of NO, a pulsed nozzle was used to expand gas samples in the vacuum chamber. Supersonic expansion provides rotational cooling of the sample which significantly simplifies its spectrum by reducing the congestion from hot band absorption.20,21 Higher selectivity for NO detection is thus allowed by using the nozzle to expand the sample gases. Other nitrogen oxides ~i.e., NO2, HNO3, N2O5! initially contained in the air gas samples are also photofragmented into NO.22,23 However, such photodissociated NO has higher rovibrational levels. By using an appropriate laser wavelength, the lower rovibrational levels of the originally contained NO can be selectively detected. At the same time, if a molecule is rotationally cooled, a higher detection efficiency can be obtained since the cooled molecules are concentrated in the lower rotational levels and can be excited more effectively using a single wavelength of light.19,20 In order to compensate for the decrease in the absolute molecular number density in the nozzle beam, ion collection was performed by using an electron multiplier in a vacuum ionization cell. II. EXPERIMENT Figure 1 presents a schematic drawing of the experimental apparatus used to detect low NO concentrations. A second harmonic of a pulsed Q-switched Nd:YAG laser ~Lambda Physik, LP 150, 5 ns duration! optically pumped a dye laser ~Lambda Physik, Scanmate 2EC!. The dye laser was frequency doubled to provide tunable ultraviolet ~UV! radiation in the region of 225–227 nm ~Coumarin 47!. With a repetition rate of 20 Hz and a pulse width of 0.13 cm21, a maximum energy of 500 mJ was obtained. UV laser power was monitored using a joulemeter ~Gentec, ED-100! as well as a photodiode. The output beam was directed to the ionization sampling cell by prisms and was passed to the central ionization region located below the nozzle and in front of the electron multiplier ~Murata, Ceratron-E, EMS-6081 B!. The laser beam is perpendicular to the molecular beam and to the 2892 Rev. Sci. Instrum., Vol. 68, No. 7, July 1997 FIG. 1. Schematic of the experimental apparatus. electron multiplier head. Operation of the pulsed nozzle and the laser was controlled by a pulse generator ~General Valve, IOTA ONE!. The ionization cell ~20 l volume! was pumped with a turbomolecular pump ~Varian, TP 550 l/s! to keep a background pressure of 131028 Torr. Even when the pulsed nozzle ~General Valve, 0.5 mm diameter, 20 Hz, 250 ms duration time! was operated to inject sampling gases into the ionization cell, a background gas pressure of 1025 Torr could still be maintained. Due to these vacuum conditions, the electron multiplier was able to be used for charge collections with high ion-collection efficiencies ~;107 gain at 2.5 kV!. The electron multiplier was located 2 cm from the laser beam so that all ions generated by the radiation could be collected. To estimate the cooling effect, ionization spectra were taken under various X/D conditions (X/D:40– 200) by changing the distance from the nozzle orifice to the ionization area (X) with a vertical manipulator ~Kitano Seiki, KMUD-34! where D corresponds to the nozzle diameter. The ionization signals measured by the electron multiplier were amplified with a gain of 125, discriminated from the background noise, and further counted by the counting units ~Hamamatsu, C3866 and M3949!. A delay of 1 ms between the laser pulse and the appearance of the ion signal allows effective separation of the ion signal from the scattered laser light pulse. The ion counts which correspond to the original ion signals were integrated for 5 s at 20 Hz and averaged over 100 laser shots. A personal computer was used for storage and data analysis. The background ionization @;5 CPS ~counts per second! at laser power of 44 mJ# was estimated by scanning the laser wavelength in the off-resonance region. The limiting noise is mainly caused by fluctuations in the nonresonant background ionization. Sample gases with different NO and NO2 concentrations were obtained by diluting 10 ppmv NO or 5 ppmv NO2 in pure N2 gases ~all Nihon Sanso, .99.9999% purity for N2!. Figure 2 illustrates the dilution system for NO detection. Four mass flow controllers ~MKS, absolute accuracy of 1%! were used for dilution of the standard gases in two successive steps. At the final step, a NO concentration of 50 pptv was obtained. To eliminate contamination caused by surface adsorption,24 the internal surfaces of the calibration lines and Low NO concentrations Downloaded¬17¬Dec¬2002¬to¬130.253.240.238.¬Redistribution¬subject¬to¬AIP¬license¬or¬copyright,¬see¬http://ojps.aip.org/rsio/rsicr.jsp FIG. 2. Gas supply system for NO MPI measurement. MFC: Mass flow controller; RP: rotary pump; PG: pressure gauge. supply lines were coated with Teflon and were baked up to 130 °C before being calibrated. III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION A. Optimization of the experimental conditions Figure 3 shows a typical NO ionization spectrum obtained when 100 ppbv NO/N2 gas was injected into the ionization cell using 44 mJ laser pulse energy and a X/D of 45. The A 2 S1←X 2 P 1/2 and A 2 S1←X 2 P 3/2 subbands are apparently separated. Each rotational line was assigned as the transition of NO from the X to the A state by using NO molecular constants25–27 and referring to the known NO ionization spectra.28–30 Figure 4 is the expanded portion of the NO ionization spectrum in the region of 226.230–226.410 nm showing the assignment for the rotational transition in the A 2 S1←X 2 P 1/2 subband. In this work, the laser wavelength was chosen to excite the P 21(1/2) line with the A 2 S1←X 2 P 1/2 transition of NO. In order to optimize the experimental conditions, NO ionization was measured by using the signal to noise ratio ~SNR! as a function of laser power, X/D for the nozzle, and electron multiplier voltage. During the measurements, the laser power varies significantly due to the shot-to-shot fluctuations and the difference in dye efficiency during the scanning. Accurate NO concentrations, therefore, could be obtained from the MPI intensities that had been normalized to the laser power. In general, for the two photon ionization FIG. 3. 111 resonance enhanced multiphoton ionization ~REMPI! spectrum of the NO ~0,0! band recorded at 100 ppbv NO/N2 gases. Rev. Sci. Instrum., Vol. 68, No. 7, July 1997 FIG. 4. Small part of the of 111 resonance enhanced spectrum of the NO A S←X 2 P 1/2 ~0,0! band showing results of the assignment for the rotational transition lines. process power dependence follows a purely quadratic behavior ~two photon transition!31 or linear behavior ~saturation of one step!.32–34 The two photon resonant enhanced multiphoton ionization of NO can be described by dn 0 /dt5 s I @ n A ~ t ! 2n 0 ~ t !# 1n A ~ t ! g , ~1! dn A ~ t ! /dt5 s I @ n 0 ~ t ! 2n A ~ t !# 2 s i In A ~ t ! 2n A ~ t ! g , ~2! dn i ~ t ! /dt5 s i In A ~ t ! , ~3! where n 0 (t), n A (t), and n i (t) are the population densities in the ground state, the intermediate A state, and the ionic state, respectively ~n 0 5N 0 and n c 5n i 50 at t50!; I is the photon flux; s (6310219 cm22) and s i @ (7.060.9)310219 22 35 cm ] are the cross sections for the one photon excitation and the one photon ionization process, respectively; and g is the effective rate for the other population loss process for the resonant A state. The time dependent equations are considerably simplified by making the assumption that the laser pulse is approximated by a step function with height I between 0 and t, i.e., during the pulse duration. If the steadystate population in the intermediate level A is assumed, i.e., dn A (t)/d(t)50, the number of ions produced after each laser shot is given by n i ' s I 2 N 0 t s i / ~ s i I1 g ! . ~4! Therefore, if the laser intensity I is strong enough, i.e., s i I @ g , then the ionization power dependence will be linear; on the other hand, if I is weak enough, i.e., s i I! g , then the ionization power dependence will be quadratic. Figure 5 shows the results of laser power dependence obtained from the Q 111 P 21(1/2) line of the NO A 2S←X 2 P 1/2(0,0) band on a logarithmic scale. From a least-square fit, it can be seen that the MPI intensity depends on the laser intensity as S} P 1.75, where S and P correspond to MPI intensity and laser power, respectively. This result indicates that the two photon NO ionization process is a ‘‘partial saturation’’ transition for laser powers of 27–55 mJ. The laser power of 40 mJ used corresponds to a photon flux of 6031024 cm22 s21 with an average laser spot size of 4.5 cm2. This result agrees well with that reported by Jacobs et al.36 They studied 111 resonance enhanced MPI spectra Low NO concentrations 2893 Downloaded¬17¬Dec¬2002¬to¬130.253.240.238.¬Redistribution¬subject¬to¬AIP¬license¬or¬copyright,¬see¬http://ojps.aip.org/rsio/rsicr.jsp FIG. 7. Variation of the NO ion signal intensity, noise, and signal-to-noise ratio ~SNR! with the high voltage setting on the electron multiplier. FIG. 5. Laser power dependence of the NO ion signal for the Q 11 1 P 21(1/2) transition of the NO A 2 S←X 2 P 1/2 ~0,0! band. by using the same NO A 2 S←X 2 P(0,0) system, and also observed a noninteger power dependence for NO ionization, 1,n,2. According to this particular power dependence of NO ionization, it is essential to monitor laser power during NO-field observations. Figure 6 shows the relationship of the NO ion intensity to the X/D for the nozzle. For both the P 211Q 11(1/2) and the P 221Q 11(1/2) branches, NO ion intensities increase with a X/D increase in the region of 35–45, and they then decrease with decreasing X/D. This observation can be explained by the fact that the number of NO molecules in the ionization area varies with the distance of X for the nozzle. In the beginning, the overlapping of the molecular beam and the laser spot increased with the increase of X and, as a result, the number of NO ions increased. After approaching the maximum at a X/D of 45, the molecular density at the laser spot decreases with an increase of X. Figure 7 shows the variation of NO ionization intensity as a function of electron multiplier voltage. At a given volt- age ranging from 2.1 to 3.5 kV, NO ion intensity was enhanced significantly since both the ion collection efficiency and detection gain became higher. On the other hand, the discrimination level setting for signal counting suppressed the noise level so that the noise strength was not increased. As a result, the SNR increases almost linearly with increasing voltage. This indicates that no saturation of charge collections occurred in this voltage region up to 3.5 kV, so it was possible to increase the election multiplier voltage to enhance the sensitivity for NO detection. B. Detection limit for NO determination Figure 8 shows the linearity of the instrument for NO calibration ranging from 100 ppbv to 10 ppmv. This calibration was carried out at high enough concentrations so that the NO ionization intensity is much higher than the zero signal. Variances in the signal intensity caused by laser power variations were normalized by monitoring laser power at the same time. The detection limit can be given approximately by @NO#limit5~S/N!~ 2S bg! 1/2C 21 t 21/2, ~5! where S bg , C, and t correspond to the background signal intensity, the instrumental sensitivity, and the integration time, respectively. In this study, the sensitivity averaged about 10 CPS/ppbv, while the background signal was about 5 CPS. A detection limit of 82 pptv (S/N52) for NO deter- FIG. 6. Relationship of NO ion intensity to X/D for the nozzle. The open circles indicate the P 211Q 11 ~0.5! line and the closed circles the P 22 1Q 11 (1/2) line. 2894 Rev. Sci. Instrum., Vol. 68, No. 7, July 1997 FIG. 8. MPI calibration line for NO measurement. Low NO concentrations Downloaded¬17¬Dec¬2002¬to¬130.253.240.238.¬Redistribution¬subject¬to¬AIP¬license¬or¬copyright,¬see¬http://ojps.aip.org/rsio/rsicr.jsp mination was obtained with an integration time of 1 min using laser power of 44 mJ, electron multiplier voltage of 2.2 kV, and X/D of 45 for the nozzle. As shown in Fig. 7, the SNR for NO detection at an electron multiplier voltage of 3.2 kV becomes more than five times higher than at 2.2 kV. Therefore, a better detection limit of 16 pptv could reasonably be obtained by setting a voltage of 3.2 kV on the ion detector. While the atmospheric air was injecting at 20 Hz with a nozzle opening time of 250 ms, the pressure of the vacuum chamber was 131025 Torr. Under such conditions, we have estimated a molecular density of about 1 31023 Torr in the nozzle beam and an absolute molecule number of 131014 of the sample gases in the ionization volume (5 cm3). Compared to the detection limit of 1 ppbv (S/N53) reported by Someonsson et al. in 1994 when using the same two photon ionization system, the detection limit has been improved by two or three orders of magnitude. This improvement may have been made possible by several factors, namely, the absolute molecular density, the ionization volume, the photon flux, and the ion collection efficiency of the detector. Although molecular density in this work is much lower than that reported by Someonsson et al. ~100 Torr!, our ionization volume is almost five orders larger since the laser beam is not focused. Jacobs et al.,36 who have also studied two photon resonance enhanced multiphoton ionization of NO using a 226 nm laser extensively, suggested that tight focusing of the laser beam could cause severe problems, such as a large gradient of laser intensity in the ionization region. The improved detection limit obtained in this work was achieved mainly by the high ion collection efficiency of the electron multiplier which produces much higher ion collection gain compared to the simple parallel electrodes that Someonsson et al. used. The low detection limit of 16 pptv (S/N52) for NO determination obtained in this study demonstrates that this laser induced two photon ionization method is a powerful technique for measurement of the tropospheric level of NO and ultimately for a better understanding of photochemical ozone formation. With the current experimental setup, however, the detection limit still critically depends on the intensity of background ionization signals, despite the fact that the nonresonant ion signals were minimized significantly by using a high vacuum ionization cell. In order to fully discriminate the NO ions from the background nonresonance ionization signals and to further substantially enhance sensitivity, a new TOF-MS is now being built. It would also be worthwhile to use a larger nozzle diameter in order to increase the molecule density in the ionization region. C. Selectivity for NO detection During the NO laser ionization, other nitrocompounds ~i.e., NO2, N2O5, HNO3! that exist in the atmosphere can also produce NO ions through photofragmentation and photoionization. First, all of these NO2-containing compounds are photolyzed to NO2 ~Ref. 18! via the process of hn R1NO2 RNO2 ——→ 226 nm; Rev. Sci. Instrum., Vol. 68, No. 7, July 1997 ~6! then NO ions are again produced as described below:22 hn NO2→ NO2* ——→ NO~ X 2 P i , v 9 ,J 9 ! 2h n 1O~ 1 D, or 1 3 P !, 2 NO~ X P i , v 9 ,J 9 ! →NO 1e . 2 ~7! ~8! Actually, these nitrocompounds were detected using an UV laser at 226 nm to photofragment and photoionize these nitrocompounds via the A 2 S←X 2 P ~0,0! band of NO.17,18 The results show that the relative sensitivities of other nitrocompounds at 193 nm are in general higher than those at 226 nm since a large fraction of the nascent NO fragment population distribution is more easily resonant with the 193 nm radiation than it is with the 226 nm radiation. Butler et al.37 and Moss et al.38 studied the population distribution of the photofragmentations of nitromethane. Their results indicate that up to 10% of the NO produced by dissociation of the NO2 photofragment may be in v 9 51 in the X 2 P state. Moreover, Morrison et al.22 reported that the NO vibrational state of v 9 51 was accessible in the two photon photodissociation of NO2→NO( v 9 )1O( 1 D) at an excitation wavelength of 450 nm. In order to eliminate interference from the photofragmentation of other nitrocompounds and to enhance selectivity for NO detection, a pulsed nozzle was used in this study. In contrast to the jet cooled NO molecules, photofragmented NO is produced in a wide distribution of rovibrational levels, and hence, selective detection for NO can be obtained. Here, only NO2 was used to study selectivity typical of nitrocompounds contained in the air. A direct comparison of ionization spectra for NO and NO2 was conducted in this study. Two spectra were recorded under exactly the same experimental conditions by introducing gases of 100 ppbv NO/N2 and 5 ppmv NO2 /N2. As a result, it was found that NO has a higher intensity of 55 compared with NO2 detection. This selectivity may be explained in terms of two factors: ~1! NO and NO2 have different ionization efficiencies due to the more complicated photoionization process in NO2 compared to NO, and ~2! the expansion process with the nozzle increases the population in the ground level of rovibrational energy for NO molecules which originally exist in the air, in contrast, NO molecules photodissociated from NO2 are excited rotationally and vibrationally. Since the ionization process for NO2 is three photon process compared to two photon process for NO, it is speculated that ionization of NO2 should have a higher laser power dependence than that of NO. We have also investigated the laser power dependence of the NO ions produced by NO2 photodissociation. In contrast to the result observed in NO ionization, S} P 1.75 as shown in Fig. 5; NO2 ionization showed a stronger power dependence, S} P 2.42, where S and P correspond to MPI intensity and laser power, respectively. Apparently, the ionization of NO2 involves a multiphoton process that makes the ionization of NO2 more strongly dependent on laser power than NO. This indicates that the selectivity depends on laser power. It is also necessary to understand how the selectivity can be improved by using a nozzle rather than by using the flow method to introduce gas Low NO concentrations 2895 Downloaded¬17¬Dec¬2002¬to¬130.253.240.238.¬Redistribution¬subject¬to¬AIP¬license¬or¬copyright,¬see¬http://ojps.aip.org/rsio/rsicr.jsp FIG. 10. Variation of rotational temperature with X/D for the nozzle. The vertical lines show the uncertainties in the calculation of the rotational temperature from the Boltzmann plot. FIG. 9. Comparison of the selectivity of NO vs NO2 for the nozzle and flow at different laser powers. The selectivity corresponds to the ratio of the ionization intensity of NO and NO2 with the same concentrations. samples. Figure 9 shows the ion intensity ratios of NO and NO2 as a function of laser power, introducing sample gases with the nozzle and flow, respectively. The same concentration of NO and NO2 gases was used, and spectra of NO and NO2 were taken under the same experimental conditions. First, it was found that the selectivity increases with decreasing laser power. This result agrees quite well with the results of differing laser power dependence for NO and NO2. Therefore, moderate laser power has to be chosen for a high sensitivity of NO detection and for a useful selectivity over other nitrocompounds. Second, the experimental results show the remarkably increased selectivity using jet expansion compared to use of the flow method. For example, a selectivity of about 50 for NO vs NO2 was obtained by using 44 mJ of pulse energy and a X/D of 120 for the nozzle compared to that of about 3 by using the flow method at the same laser power. Since the selectivity is a function of laser power, this high selectivity of 50 will be conserved even if NO concentrations decrease as low as 16 pptv ~the detection limit for NO determination! at a laser power of 44 mJ. This demonstrates that for a selective measurement of NO a nozzle is an effective tool for introducing gases. In order to better understand the cooling effect of the nozzle, the rotational temperature of NO was calculated from the Boltzmann plot using the NO ionization spectra recorded at different values of X/D and using the known energy level formulas of NO and Hönl–London factors.26 As can be seen in Fig. 10, the calculated rotational temperatures of NO are between 35 and 25 K for X/D between 40 and 70. The temperatures obtained indicate an increase in population of relatively low rovibrational states of the electronic NO ground level. This therefore demonstrates that the high selectivity for NO resulted from the expansion process of the gas jet. In summary, by using a nozzle, interference from the other nitrocompounds can be reduced. Besides the cooling effect, multiphoton dissociation and the ionization process for these NO2-containing compounds are also responsible for the significant selectivity for NO measurement. Although 2896 Rev. Sci. Instrum., Vol. 68, No. 7, July 1997 only NO2 gases were chosen for the selectivity experiment in the present study, it may be expected that interference from other nitrocompounds in ambient air may be smaller than that from NO2 since they are all photodissociated to NO2 first. For example, HNO3 is photodissociated to NO2 primarily as39 hn HNO3→ OH1NO2, and therefore the ionization efficiency can be expected to be much lower than that for NO2. IV. DISCUSSION A new method for the detection of low levels of nitric oxide was developed for measurements of background NO concentrations in the troposphere. The measurement apparatus used a 226 nm pulsed dye laser to ionize NO by resonance enhanced two photon ionization via its A 2 S←X 2 P(0,0) band on a pulsed gas jet. The experimental conditions were optimized for high sensitivity NO detection as a function of laser power, electron multiplier voltage, and X/D. The detection limit of NO was as low as 16 pptv (S/N52). Using the pulsed nozzle to introduce sample gases, improved selectivity over the flow method was obtained. The selectivity depends on laser power. In order to eliminate the background ionization signal to improve the NO measurement sensitivity, a time of flight mass spectrometer is now being built. The improved spectrometer planned for use in the detection of background NO at remote sites in Japan to obtain data for photochemical modeling of the troposphere. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS One of the authors ~S.L.! would like to thank Professor T. Kondow of The University of Tokyo for his continuous encouragement during this work, and she is also grateful to Dr. K. Hukutani and Dr. T. Tsukuta for their scientific and technical advice. This work was partially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science ~JSPS!. Low NO concentrations Downloaded¬17¬Dec¬2002¬to¬130.253.240.238.¬Redistribution¬subject¬to¬AIP¬license¬or¬copyright,¬see¬http://ojps.aip.org/rsio/rsicr.jsp S. C. Liu, D. Kley, and M. McFarland, J. Geophys. Res. 85, 7546 ~1980!. NASA Conference Publication 2292 ~NASA, 1983!. 3 J. E. Sickles, Gaseous Pollutants ~Wiley, New York, 1989!, pp. 51–128. 4 A. L. Torres, J. Geophys. Res. 90, 12 875 ~1985!. 5 M. A. Carroll, M. McFarland, B. A. Ridley, and D. L. Albritton, J. Geophys. Res. 90, 12 853 ~1985!. 6 B. A. Ridley and L. C. Howlett, Rev. Sci. Instrum. 45, 742 ~1974!. 7 Y. Kondo, A. Iwata, and M. J. Takagi, J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 61, 845 ~1983!. 8 J. D. Bradshaw, M. O. Rodgers, S. T. Sandholm, S. Ke Seng, and D. D. Davis, J. Geophys. Res. 90, 12 861 ~1985!. 9 S. T. Sandholm, J. D. Bradshaw, K. S. Dorris, M. O. Rodgers, and D. D. Davis, J. Geophys. Res. 95, 10 155 ~1990!. 10 H. Ender, A. Sunesson, and S. Svanberg, Opt. Lett. 13, 704 ~1988!. 11 R. K. Stevens and T. L. Vossler, Proc. SPIE 1433, 25 ~1991!. 12 H. Hallstadius, L. Une’us, and S. Wallin, Proc. SPIE 1433, 36 ~1991!. 13 P. M. Johnson and C. E. Otis, Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 32, 139 ~1981!. 14 G. S. Hurst, M. H. Nayfeh, and J. P. Young, Phys. Rev. A 15, 2283 ~1977!. 15 J. H. Brophy and C. T. Rettner, Opt. Lett. 4, 337 ~1979!. 16 A. V. Smith, A. W. Johnson, and R. J. M. Anderson, Technical Digest of the Congress of Lasers and Electro-Optics ~Optical Society of America, Washington, DC, 1982!. 17 J. B. Simeonsson, G. W. Lemier, and R. C. Sausa, Anal. Chem. 66, 2272 ~1994!; Appl. Phys. 47, 1907 ~1993!. 18 G. W. Lemier, J. B. Simeonsson, and R. C. Sausa, Anal. Chem. 65, 529 ~1993!. 19 S. Guizard, D. Chapouland, M. Horani, and D. Gauyacq, Appl. Phys. B 48, 471 ~1989!. 20 D. H. Levy, L. Wharton, and R. E. Smalley, Chemical and Biological Applications of Lasers ~Academic, New York, 1977!, Vol. II, Chap. 1. 1 2 Rev. Sci. Instrum., Vol. 68, No. 7, July 1997 21 R. E. Smalley, L. Wharton, and D. H. Levy, J. Chem. Phys. 61, 4363 ~1974!. 22 R. J. S. Morrison, B. H. Rockney, and E. R. Grant, J. Chem. Phys. 75, 2643 ~1981!. 23 I. T. N. Jones and K. D. Bayes, J. Chem. Phys. 59, 4836 ~1973!. 24 Y. Kondo, A. Iwata, M. Takagi, and W. A. Matthews, Rev. Sci. Instrum. 55, 1328 ~1984!. 25 R. Engleman, Jr. and P. E. Rouse, J. Mol. Spectrosc. 37, 37 ~1971!. 26 W. G. Mallard, J. H. Miller, and K. C. Smyth, J. Chem. Phys. 76, 3483 ~1982!. 27 G. Herzberg, Molecular Spectra and Molecular Structure ~Van Nostrand, New York, 1950!, Chap. 5. 28 H. Zarcharias, R. Schmiedl, and K. H. Welge, Appl. Phys. 21, 127 ~1980!. 29 K. Mase, K. S. Mizuno, Y. Achiba, and Y. Murata, Surf. Sci. 242, 444 ~1991!. 30 Y. Luo, Y. D. Cheng, H. Agren, R. Maripuu, W. Seibt, L. Ohlund, P. Ejeklint, B. Carman, K. Z. Xing, Y. Achiba, and K. Siebahn, Chem. Phys. 153, 473 ~1991!. 31 H. Parker, Ultrasensitive Laser Technique ~Academic, New York, 1983!. 32 M. Asscher, W. L. Guthrie, T.-H. Lin, and G. A. Somorjai, Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 76 ~1982!. 33 N. Goldstein, G. Greenblatt, and R. Wiesenfeld, Chem. Phys. Lett. 96, 410 ~1983!. 34 I. C. Winkler, R. Stachnik, J. Steinfeld, and S. Miller, Spectrochim. Acta A 42, 339 ~1986!; J. Chem. Phys. 85, 890 ~1986!. 35 H. Zacharias, R. Schmiell, and K. H. Welge, Appl. Phys. 21, 127 ~1980!. 36 D. C. Jacobs, R. J. Madix, and R. N. Zare, J. Chem. Phys. 85, 5469 ~1986!. 37 L. J. Butler, D. Krajnovich, Y. T. Lee, G. Ondrey, and R. Bersohn, J. Chem. Phys. 79, 1708 ~1983!. 38 D. B. Moss, K. A. Trentelman, and P. L. Houston, J. Chem. Phys. 96, 237 ~1992!. 39 H. Okabe, Photochemistry of Small Molecules ~Wiley, New York, 1978!, Chap. 7. Low NO concentrations 2897 Downloaded¬17¬Dec¬2002¬to¬130.253.240.238.¬Redistribution¬subject¬to¬AIP¬license¬or¬copyright,¬see¬http://ojps.aip.org/rsio/rsicr.jsp