Food and Agricultural Education in the United States

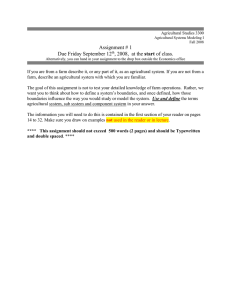

advertisement