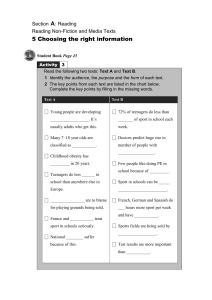

Research on China`s University and College Sport: An Analysis of

advertisement