Revisiting `Rabbit`: A Fanatical Ambiguity Monger Gets Her Way

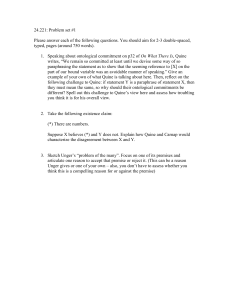

advertisement