Reducing Soft Tissue Injury and Realizing Significant

advertisement

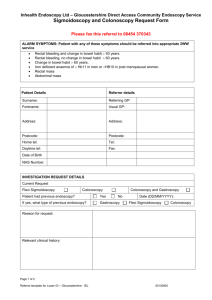

Reducing Soft Tissue Injury and Realizing Significant Cost Savings Through Use of Innovative New Endoscopy Device Jim Slattery RN, CGRN Colonoscopy is a procedure performed in hospitals and freestanding clinics to diagnose and evaluate the heath status of the bowel. The goal of the procedure is to reach an anatomic landmark called the ileocecal valve, thus allowing for complete evaluation and treatment of colonic disease states and detection and removal of pre-cancerous polyps. As part of the procedure, endoscopy personnel are required to press firmly on the abdomen. N-Doe Pillow™ is a unique new device available exclusively through N.M. Beale Company, Inc. It allows for hands free compression of the abdomen during colonoscopy. Abdominal pressure applied by the nurse or assistant provides countertraction to aid in the prevention and management of scope loop formation. (Fig 1) Without this assistance, reaching the target can be exceptionally difficult to achieve by the endoscopist. Techniques for counter pressure have been well described in the literature, and include closed hand, open hand and forearm methods. Each has its advantages and disadvantages. Fig. 1: Looping During Colonoscopy In the closed hand method the fist is used at various points on the abdomen. The ability to feel loop formation with the fingertips is lost and the shoulder and neck muscles provide the force necessary. Extension of the forearm places stress on the triceps and shoulder, while during the open handed method, where the senses of touch are most acute, the wrist is hyperextended. The Problem While one of the above methods, or a combination of them, may be preferable to a particular individual, they all have one thing in common: these repeated stresses on joints, muscles and ligaments result in fatigue and micro-tears resulting in soft tissue injuries (STIs). page 1 Scope and Prevalence of the Problem The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has estimated that there are 14.2 million colonoscopies performed each year in hospitals in the United States for colo-rectal cancer screening and could increase to 22.4 million annually. Freestanding clinics do not have the reporting obligations that hospital based units do. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), another 136 million individuals are in need of screening for colon cancer. STIs are the most common work related injuries, accounting for millions of dollars in lost time at work, pain and reduced quality of life. The hospital industry is the third most expensive of 313 U.S. industries resulting in 900 million dollars in cost of work-related injury and illness in 1993. [Waehrer] Endoscopy personnel become afflicted with acute and chronic injuries to the soft tissues of the hand, arm, shoulder and neck as a result of assisting with colonoscopy. [Drysdale] A number of studies examine the incidence, disabilities and quality of life as a result of soft tissue injuries (STI). The DASH Questionnaire is a scoring method that is widely utilized by orthopedic surgeons to determine disability of the shoulder, arm and hand. The questionnaire, once scored, helps determine the limitations in activity and quality of life. The score range is 0-100. The general population has a DASH score 8.8. The mean DASH score for the Canadian endoscopy study group was 15.8. This finding was confirmed by Drysdale in the US questionnaire. The following facts have been established: 1) 36% of endoscopy nurses have or have had acute or chronic STI. 2) 5 9.9% see a doctor because of pain in the hands, wrists, shoulders and neck. 3) U p to 45% take over-the-counter non-steroidal medications to treat said pain. 4) 3 2.7% of sick time used by the nurses in the study (n=147) was because of STI/pain issues. 5) Mean hands-on pressure is delivered for 6.3 minutes per case. While the above figures are alarming, the extent of STI on endoscopy personnel is not fully known, as it is suspected to be under reported. An endoscopy nurse or assistant may assist with up to 50 colonoscopies per week — the equivalent of holding a push up position for 5 hours! In addition to applying hand and/or forearm pressure, the nurse or assistant is also required to aid the sedated patient to move into different positions as an additional method for loop control, incurring back stress in the process. Sedated patients may be moved 2-3 times per case and moving a sedated patient during colonoscopy can injure back muscles. Clearly, there is a huge need to address the problem. Ideally, the solution would involve less hands-on time, and less repositioning. page 2 The Solution A unique device called the N-Doe Pillow™ has been developed to meet this challenge. It was invented by a 30 year veteran of endoscopy nursing whose own injuries were severe enough that he feared a career change may be necessary. He searched for a tool that would aid him but found no device to address these issues. After experimenting for almost a year, he developed a soft but firm device that uses a combination of the patient’s body weight and leveraging to safely and effectively allow compression in the right areas without requiring pressure form the nurse or assistant’s hands. Using this innovative device, his DASH score improved by 50% in one month. The device was introduced to the public as the N-Doe Pillow.™ Fulcrum Points How It Works Palpation Arch The N-Doe Pillow is designed to provide focal pressure to the abdomen, rather than pressure provided by the endoscopy assistant. Contact Columns After the patient is sedated and positioned, the N-Doe Pillow is used to compress three different zones, singularly or in combination, to control loop by counter traction. The patient’s own body weight helps to keep the device in place. By using the N-Doe Pillow as directed, the nurse or assistant’s hands are free to be used for palpation instead of pressure, and patient position changes are rare. 2 3 1 The N-Doe Pillow is easy to use, affordable and reusable. Three pressure zones on the abdomen are compressed with N-DOE PILLOW™ singularly or in combination, to control loop by counter traction. For a VIDEO demonstration of the N-DOE PILLOW™ visit www.nmbco.com/pillow.html page 3 SOURCES: Anderson, Joseph C., Catherine R. Messina, William Cohn, Edward Gottfried, Scott Ingber, Gary Bernstein, Eugene Coman, and Joseph Polito. “Factors Predictive of Difficult Colonoscopy.” Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 54.5 (2001): 558-62. Print. Arcovedo, Rodolfo, Charles Larsen, and Hector Salazar Reyes. “Patient Factors Associated with a Faster Insertion of the Colonoscope.” Surgical Endoscopy 21.6 (2007): 885-88. Print. “Baby Boomers.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, n.d. Web. 30 Jan. 2014. <http://www.history.com/topics/baby-boomers>. Bell, G. D., R. S. Rowland, M. Rutter, M. Abu-Sada, S. Dogramadzi, and C. Allen. “Colonoscopy Aided by Magnetic 3D Imaging: Assessing the Routine Use of a Stiffening Sigmoid Overtube to Speed up the Procedure.” Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing 37.5 (1999): 605-11. Print. Catalano, Filippo, Roberto Catanzaro, Giuseppe Branciforte, Carmelo F. Bentivegna, Rosanna Cipolla, Alfio Brogna, Lucia O. Sala, Giuseppe Migliore, and Mario Paternuosto. “Colonoscopy Technique with an External Straightener.” Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 51.5 (2000): 600-04. Print. Darby, Barbara, Ana-Maria Gallo, and Willa Fields. “Physical Attributes of Endoscopy Nurses Related to Musculoskeletal Problems.” Gastroenterology Nursing 36.3 (2013): 202-08. Print. “De Quervain’s Tenosynovitis.” Eorthopod.com. Www.northamericanspine.com, n.d. Web. 27 Jan. 2014. <http://www.eorthopod.com/content/de-quervains-tenosynovitis>. Dechêne, Alexander, Christoph Jochum, Lars P. Bechmann, Susanne Windeck, Guido Gerken, Ali Canbay, and Thomas Zöpf. “Magnetic Endoscopic Imaging Saves Abdominal Compression and Patient Pain in Routine Colonoscopies.” Journal of Digestive Diseases 12.5 (2011): 364-70. Print. Drysdale, Susan A. “The Incidence of Upper Extremity Injuries in Endoscopy Nurses Working in the United States.” Gastroenterology Nursing 36.5 (2013): 329-38. Print. Drysdale, Susan. “The Incidence of Upper Extremity Injuries in Canadian Endoscopy Nurses.” Gastroenterology Nursing 34.1 (2011): 26-33. Print. Edgelow, C., and R. Hucke. “The Importance of Positioning During Colonoscopy.” The Importance of Positioning During Colonoscopy. N.p., n.d. Web. 28 Jan. 2014. <http://www.endonurse.com/articles/2007/08/the-importance-of-positioning-during-colonoscopy.aspx>. How Many Endoscopies Are Performed for Colorectal Cancer Screening? Results from CDC’s Survey of Endoscopic Capacity. N.p.: n.p., n.d. Web. Hsieh, Yu-Hsi, Kuo-Chih Tseng, and An-Liang Chou. “Patient Self-Administered Abdominal Pressure to Reduce Loop Formation During Minimally Sedated Colonoscopy.” Digestive Diseases and Sciences 55.5 (2010): 1429-433. Print. &na;. “Safe and Effective Abdominal Pressure During Colonoscopy.” Gastroenterology Nursing 32.1 (2009): 31-32. Print. Prechel, J. A., C. J. Young, T. M. Young-Fadok, and D. E. Fleischer. “The Importance of Abdominal Pressure during Colonoscopy: Techniques to Assist the Physician and to Minimize Injury to the Patient and Assistant.” Gastroenterol Nurs. 28.3 (2005): 232-36. Print. Prechel, James A., and Ray Hucke. “Safe and Effective Abdominal Pressure During Colonoscopy.” Gastroenterology Nursing 32.1 (2009): 27-30. Print. Rathgaber, Scott W., and Theresa M. Wick. “Colonoscopy Completion and Complication Rates in a Community Gastroenterology Practice.” Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 64.4 (2006): 556-62. Abstract. (n.d.): n. pag. Print. Sanaka, Madhusudhan R. “Secrets of Success in a Difficult Colonoscopy.” Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 69.2 (2009): 390-91. Print. Sato, Koichiro, Sumio Fujinuma, and Yoshihiro Sakai. “Evaluation Of The Looping Formation And Pain During Insertion Into The Cecum In Colonoscopy.” Digestive Endoscopy 18.3 (2006): 181-87. Print. Saunders, Brian P., Manabu Fukumoto, Steve Halligan, Craig Jobling, Mohammed E. Moussa, Clive I. Bartram, and Christopher B. Williams. “Why Is Colonoscopy More Difficult in Women?” Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 43.2 (1996): 124-26. Print. Seef, L. C., T. B. Richards, J. A. Shapiro, M. R. Nadel, D. L. Mannanin, L. S. Given, F. B. Dong, and L. D. Winges. “How Many Endoscopies Are Performed for Colorectal Cancer Screening? Results from CDC’s Survey of Endoscopic Capacity.” Trans. M. T. McxKenna. Gastroenterology 127.6 (2004): 1670-677. Print. Shergill, Amandeep K., Kenneth R. Mcquaid, and David Rempel. “Ergonomics and GI Endoscopy.” Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 70.1 (2009): 145-53. Print. Sivak, M. V. “Gastrointestinal Endoscopy: Past and Future.” GUT 55.8 (2006): 1061-064. Print. Smedley, J., H. Inskip, F. Trevelyn, P. Buckle, C. Cooper, and D. Coggon. “Risk Factors for Incident Neck and Shoulder Pain in Hospital Nurses.” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 60.11 (2003): 864-69. Print. N= 587 34% had at least 1 episode of neck/shoulder pain. Associated with patient handling, reaching/pushing/pulling/lifting Trinkoff, Alison M., Barbara Brady, and Karen Nielsen. “Workplace Prevention and Musculoskeletal Injuries in Nurses.” JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration 33.3 (2003): 153-58. Print. Tsutsumi, S., H. Fukushima, and H. Kuwano. “Colonoscopy Using an Abdominal Bandage.” Hepatogastroenterology 54.79 (2007): 1983-984. Print. United States. NIH. Personal Safety for Nurses. By Alison M. Trinkoff, Jeanne M. Geiger-brown, Clair C. Caruso, Jane A. Lipscom, Meg Johantgen, Audry L. Nelson, Barbara A. Sattler, and Victoria L. Selby. NIH, Nov.-Dec. 2001. Web. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2661>. Waye, Jerome D., Siroun A. Yessayan, Blair S. Lewis, and Thomas L. Fabry. “The Technique of Abdominal Pressure in Total Colonoscopy.” Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 37.2 (1991): 147-51. Print. Wolf, W. I. “Colonoscopy: History and Development.” Am J Gastroenterology 84.9 (1989): 1017-025. Print. Zuber-Jerger, Ina, Esther Endlicher, and Cornelia Maria Gelbmann. “Factors Affecting Cecal and Ileal Intubation Time in Colonoscopy.” Medizinische Klinik 103.7 (2008): 477-81. Print. page 4