Workplace Functional Impairment Due to Mental Disorders

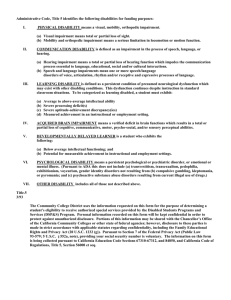

advertisement