Smoking Restrictions in the Workplace

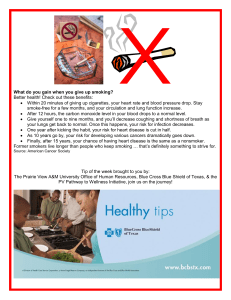

advertisement