PDF - Read online

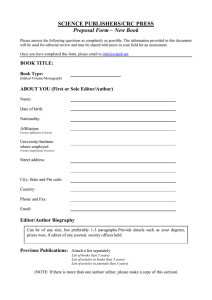

advertisement