Fertility in India - East

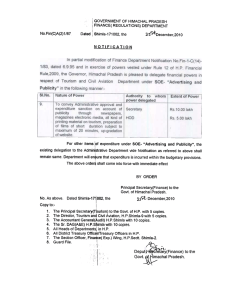

advertisement