Reprinted from

II March 1977, Volume 195, pp. 1002-1004

Species Identification in the North American Cowbird:

Appropriate Responses to Abnormal Song

Andrew P. King and Meredith J. West

Copyright© 1977 by the A merican Association fOT the Advancement oj Science

•

Species Identification in the North American Cowbird:

Appropriate Responses to Abnormal Song

Abstract. Female cowbirds raised in auditory isolation from males responded to

the songs of male cowbirds with copulatory postures. The songs of males reared in

isolation were more effective in eliciting the posture than the songs of normally

reared males. The females did not respond to the songs of other species. These re­

sults indicate one mechanism of species identification for this parasitic species.

M0-

courtship and is accompanied by a bow­

lothrus ater, is reported to parasitize

more than

200 species (1). Thus, unlike

ing display. We collected data from a

small group of males that suggested that

most vertebrates, young cowbirds are

male peer experience was sufficient to

not

con­

produce normal adult courtship song.

specific parents during their earliest inter­

However, males reared in isolation from

actions with adults or peers. Although

both male peers and adults, developed

much remains to be learned about the de­

songs that differed from the normal ver­

velopmental impact of such stimulation,

sion, particularly in the extent to which

there is growing evidence to demonstrate

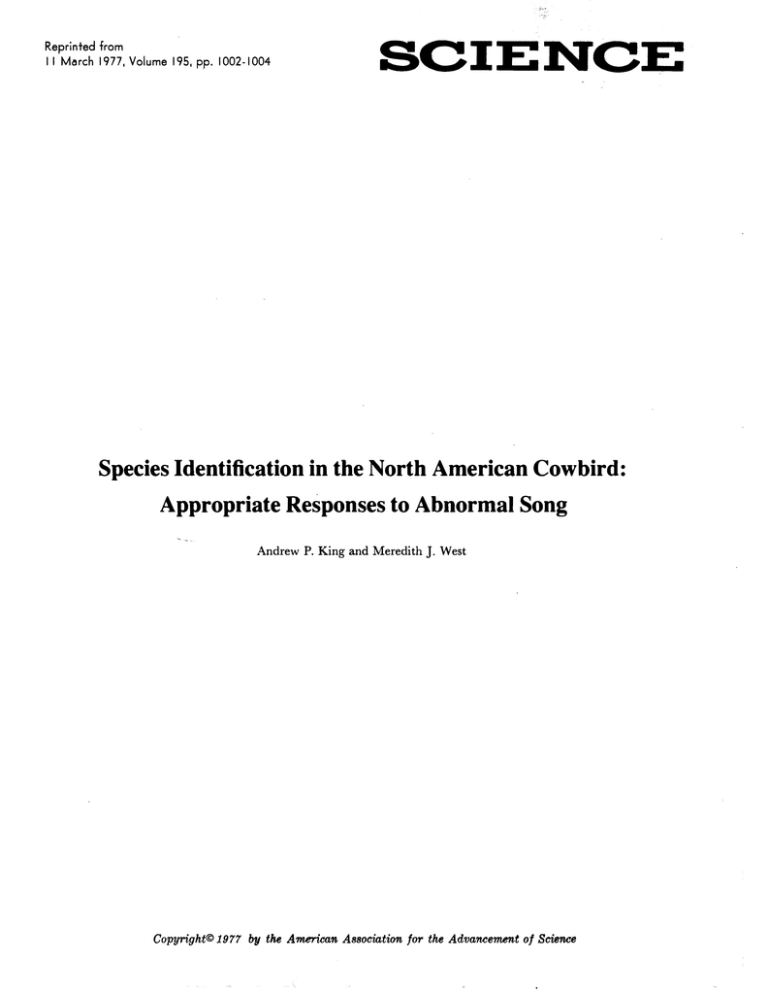

some of the notes are mod�lated (Fig.

The

brown-headed

exposed

to

cowbird,

stimulation

by

its facilitative role in avian species identi­

2).

The following experiments were de­

(2). How, then, does the cow­

signed to elaborate upon these observa­

bird, naturally deprived of such experi­

tions by testing other naive females. The

ence, come to identify other cowbirds?

songs of both normal and isolate males

This question has puzzled students of de­

were included to help clarify the role of

velopment and evolution for many years,

peer experience in song development.

fication

and, until now, only speCUlative solu­

The subjects were six female cowbirds

tions existed (3). We report a series of ex­

raised in auditory and visual isolation

periments detailing a mechanism of spe­

from adult cowbirds. Their prenatal audi­

cies identification that allows us to under­

tory experience was controlled in that

stand how cowbirds have evolved to

eggs were obtained from a captive colo­

overcome the fact that they were not

ny of cowbirds and incubated in isola­

reared by conspecifics.

tion. Their postnatal social contact was

Two findings led to the discovery of

limited to a

1- to 5-day period during

this mechanism. First, we had raised a fe­

which the individual eggs hatched into

male cowbird in the laboratory in com­

barn swallow (Hirundo rustica) nests,

plete auditory and visual isolation from

and the young birds were fed by their

other cowbirds. At 8 months of age, she

hosts. After being returned to the labora­

was exposed to a recording of male cow­

tory, they were hand-reared as a group

bird courtship song. She adopted a pos­

without contact with adult cowbirds.

ture we term the "copulatory response":

They were placed in soundproof cham­

her

wings were lowered and

spread

bers between the ages of 35 and

60 days

apart, her neck and body were arched,

(4). The birds were housed in pairs to al­

and the feathers around the cloacal re­

gion were separated (Fig.

1). A series of

low the opportunities for social inter­

action and auditory experience thought

playbacks confirmed the specificity of

to be essential for the birds to come into

the response: she showed no response to

breeding condition. Chambers

the songs of a red-winged blackbird

each housed two female cowbirds; cham­

1 and 2

(Agelaius phoeniceus) or to the cowbird

ber 3, a female cowbird and a female red­

flight call.

winged blackbird; chamber 4, a female

The second finding related to the de­

cowbird and a male cowbird; chamber 5,

velopment of the male song. Male cow­

a male cowbird and a male cardinal

bird song, which can be transcribed as

(Richmendena

"burble

phase of their photoperiods was gradu-

burble

.

j

tsee," occurs during

cardinalis).

The

light

�'---'.

--

"

cowbird, was transferred to a chamber

housing a female canary 3 weeks before

the

1976 testing. Also, two samples of

16

-

NORMAL

12

8

parts of the abnormal song were used: (i)

the "burble-burble" phrase alone, (ii)

the "tsee" alone, and (iii) a new sample

4

16

of abnormal song from another isolate

12

male.

The abnormal song retained its superi­

or effectiveness, and abnormal, normal,

and

partial-abnormal

songs

were

all

more effective than the controls (Table

Fig. 1. Female cowbird displaying the copula­

tory response.

ABNORMAL

1). The differences among the conditions

were reliable (Friedman two-way analy­

sis of variance, Xr2

=

23.3, P <

.001).

Both samples of abnormal song were

ally extended during the spring months.

equally effective, and one of the partial

The playback period began in May

songs was more effective than the full

(6). Female CB, despite her

1975, when the birds were 9 months old,

normal song

and was conducted in two phases. In the

sexual experience and her lack of re­

first phase, the females were exposed to

sponding in the earlier experiment, re­

recordings of normal cowbird song ob­

sponded as strongly as the sexually naive

tained from a wild-caught male and the

females

8

4

r

•

O�

____

�

.

r \��,�

,.. III �

'�.

__"L�

'

�

'� ��

" I

'

_

II

R

________

_

'"

,

1----112 II< -----I

Fig. 2. These recordings were made on a sono­

graph (Kay) with a wide-band filter and set for

flat response and linear display. The units on

the ordinate are kilohertz. The most striking

difference is the rapid modulation between 2

and 8 khz present in the abnormal but not the

normal song. This type of modulation was not

present in any of a sample of 522 song spectro­

graphs obtained from a captive colony of nor­

mally reared male cowbirds (10).

(7).

control songs of male red-winged black­

Another piece of evidence attests to

tory and sexual experience with males

birds, meadowlarks (Sturnella magna),

the potency of the abnormal song as a

does not diminish the effectiveness of the

and Baltimore orioles (Icterus galbula).

sexual releaser. Two wild female cow­

abnormal song.

There

birds were captured and placed in the lab­

were

four

playbacks

spread

1976. While in

In summary, these data indicate that

throughout each day; the order of pre­

oratory in the winter of

sentation varied each day but was the

these

but

experience with adult cowbirds in order

same for each bird. In the second phase,

could not see, caged male cowbirds and

for species identification to occur. Naive

the procedure was identical except that

male and female free-living cowbirds. Al­

females

... the playback series included the abnor­

'tal song of an isolate male. The re­

though a full series of playbacks was not

song; naive males produce an acoustical­

carried out owing to the birds' nervous­

ly atypical, but highly effective, song.

presence or ab­

ness in captivity, the first time the abnor­

Isolate song, then, appears to have quali­

mal song was played to them, one of the

ties of a "supernormal" releaser. Why

During the first phase, four of the six

females immediately adopted the copUla­

normal song appears less effective is as

female cowbirds responded more often

tory posture. In subsequent exposures,

yet unspecified, but it may reflect the

to normal song than to any of the control

fact that males sing in contexts other

songs (Table

1). One of these, female

she continued to respond to the abnor­

mal song but never to the normal. Thus,

than courting. The songs of males, there­

DB, showed a dual preference for cow­

response to abnormal song was not re­

fore, may contain more complex mes­

bird and meadowlark song. The fifth cow­

stricted to females raised in isolation.

sages indicating not only the species,

bird, female W, did not come into breed­

Furthermore, the response of this female

sex, or breeding condition of the singer,

ing condition and hence did not respond.

and that of female CB suggest that audi-

but agonistic or territorial information as

•

\......sponse measure was the

sence of the copulatory posture

(5).

surroundings,

they

heard,

neither male nor female cowbirds require

respond

adaptively

to

male

The sixth, female CB, was housed with

the male cowbird and also showed no

response. She was observed, however,

to copUlate frequently. The variability

across the females was probably due to

variations in breeding condition, which

was indicated by the numbers of eggs

laid.

During the second phase, four females

demonstrated a clear preference for the

abnormal song (Table

1). For each of the

four birds, the abnormal song produced

the highest rates of response, the normal

song the second highest and the control

songs of the other species the lowest

rates.

/.

In order to pursue this finding in great­

�

'"

detail, the birds were maintained in

\,--tSolation for another year and retested in

\

the spring of

1976. Several procedural

changes were also made. Female CB,

which had been reared with the male

•

.

well. A closer assessment of the function­

another. Little is known about cowbird

al properties of the songs of normally

social behavior, yet data from our labora­

reared males may help to clarify these

tory indicate that cowbirds have highly

speculations. In addition, these data sug­

structured dominance hierarchies and

gest the need to examine in more detail

complex intraspecific behaviors that may

the developmental role of self-stimula­

also facilitate identification or maintain

tion. It may be that the self-generated

social integration among acquainted cow­

sounds of the isolate males channeled

birds

their song development toward an em­

scribed might represent an independent

phasis on the acoustic properties that

system designed to ensure identification

contain the sexual message in cowbird

during the most important context, the

song.

Males reared with other males,

breeding season, and to enhance repro­

however, whether age mates or adults,

ductive opportunities by inducing sex­

may receive acoustically more varied

ually appropriate behavior in the female.

stimulation, may learn to modify their

Thus,

song components as a result of auditory

multiple means to identify one another,

and behavioral feedback from their com­

the presence of a mechanism geared di­

panions (thereby leading to a dilution of

rectly for reproduction may represent a

the purely sexual message), or both. In

critical adaptation for a parasitic species.

any case, these data implicate self-stimu­

ANDREW P. KING

(9).

The mechanism we have de­

although

cowbirds

lation as possibly a very important form

Department of Psychology,

of species-typical experience for cow­

Cornell University,

birds as has been hypothesized

Ithaca, New York

(8).

Final­

5.

may

have

14850

MEREDITH J. WEST*

Iy, although it is tempting to label the

cowbird's response to isolate song as id­

Department of Psychology,

iosyncratic or unrepresentative of other

University of North Carolina,

songbirds, this cannot be done, as little

Chapel Hill

6.

7.

27514

late songs. Such information would be

useful in species that, like the cowbird,

have courtship songs. Songs of a primari­

ly territorial nature may be more difficult

to assess.

Although these results provide one an­

swer to the question of the mechanism

by which cowbirds identify one another,

they do not explain how young or juve­

nile cowbirds first come to recognize one

References and Notes

I. H. Friedmann, U.S. Natl. Mus. Bull. 233,

6,

8.

9.

(1963).

2. G. Gottlieb,

Development 0/ Species Identifica­

tion: An Inquiry into the Prenatal Determinants

o/Perception (Univ. of Chicago Press, Chicago,

1971).

3. D. Lehrman, in Ethology

and Psychiatry, N. F.

White, Ed. (Univ. of Toronto Press, Toronto,

1974) pp. 187-197; E. Mayr, Am. Sci. 62, 650

(1974).

4. Each chamber consisted of two concentric

boxes constructed of elywood and sheetrock.

Wood and acoustic ule baffles between the

boxes were designed to be most effective be­

tween 2 and 16 khz. Suppression was greater

tested with t-tests. Reliable differences were

obtained for the following comparisons: abnor­

mal one or two versus normal song (abnormal

11.04, P < .001; abnormal two:

one: t

t = 9.95; P < .(01); abnormal versus control

songs (abnormal one: t = 8.85, P < .001; abnor­

mal two: t = 19.43, P < .(01); normal versus

control song (t = 6.09, P < .(01); the "burble"

phrase versus the "tsee" phrase (t = 3.17,

P < .05); and either partial song versus the nor­

mal "burble" (t = 4.22, P < .(01). There was

no reliable difference between the two samples

of abnormal song or between the "tsee" phrase

and normal so

. ng.

Female CB's lack of response the previous year

probably resulted from her being housed with a

male cowbird, who repeated his sorog to her

many times each day, thus raising her threshold

for song responsiveness. Furthermore, her com­

panion's song was undoubtedly of superior

acoustic quality, a factor that might also have

diminished her interest in the recorded songs.

G. Gottlieb, Psychol. Bull. 79, 362 (1973).

A. King, paper presented at the meeting of the

Animal Behavior Society, Wilmington, N.t., 22

to 27 May 1975.

D. Eastzer, thesis, Cornell University (1975).

We thank G. Wilcox who designed the isolatior

chambers, R. Chu and D. Eastzer who helped i

the field by collecting eggs and nestlings, R. E��

Johnston for valuable suggestions during the

initial stages of this - project, and P. Cabe, W.

Dilger, D. Miller, P. Ornstein, and H. Rhein­

gold for helpful comments on the manuscript.

We are especially grateful to G. Gottlieb for

both technical and conceptual assistance.

Request for reprints should be sent to M,J. W.

=

comparative information exists regard­

ing the responses of other species to iso­

than 39 db at 1000 hertz, and it increased with

higher frequencies to greater than 50 db between

8 and 16 khz. The interior box was a I. l-m cube,

fabric-lined to reduce sound reflection, lighted

by two 40-watt Vita Lite tubes and continuously

ventilated. White noise was broadcast in the

room housing the chambers.

The songs were recorded with a dynamic mien"

/

phone (Uher 5(7) and tape recorders (Uher-4000). The recordings were played through a

driver (JBL 2420) and hom (JBL 2340). Play­

back levels were determined with a sound pres­

sure meter (General Radio 1933). The same

sound pressure levels (SPL's) \\ere used for

playbacks of the normal and the abnormal

songs. At 0.35 m from the speaker along the

axis, the SPL was 86 ± 1.5 db slow reading and

104 + 1.5 db impulse. Control songs of the other

species were adjusted to the slow reading. The

A-weighted SPL inside the chamber was 50 db

slow reading.

Differences between categories of song were

10.

11.

15 September 1976; revised 15 November 1976

"