182436_Catalogue 2008-09 TEXT.qxp:171056_Catalogue 2007

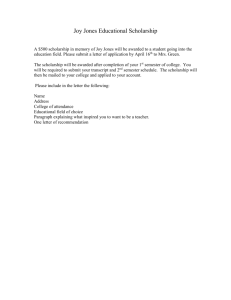

advertisement