Socioeconomic Status and Academic Achievement

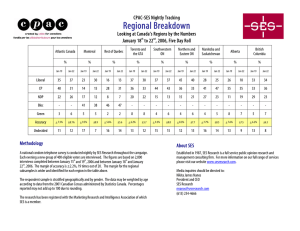

advertisement