An Assessment of Policy Measures to Support Russia`s Real Economy

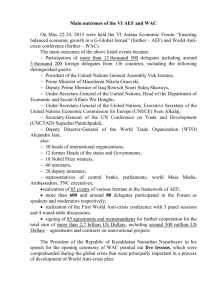

advertisement