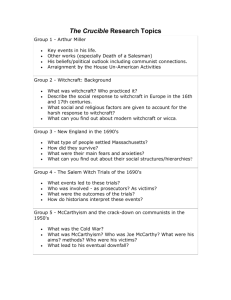

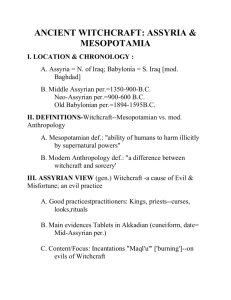

Covert Power: Unmasking the World of Witchcraft e Origins and

advertisement