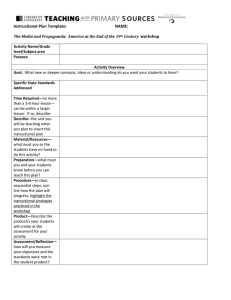

Combining Different Ways of Learning and Teaching in a Dynamic

advertisement