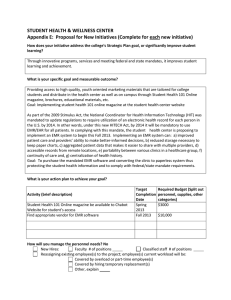

Implementation Plan for EMR and Beyond

advertisement