from uncg.edu - The University of North Carolina at Greensboro

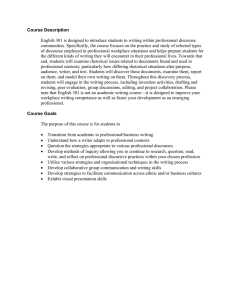

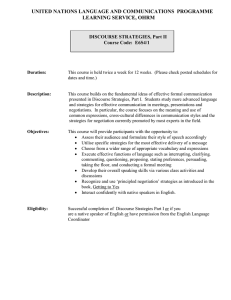

advertisement