The `T5` Design Model: An Instructional Model and Learning

advertisement

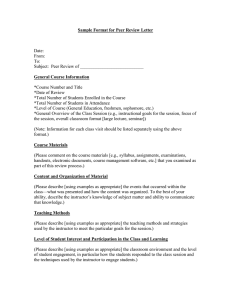

The ‘T5’ Design Model: An Instructional Model and Learning Environment to Support the Integration of Online and Campus-Based Courses Diane Salter, Leslie Richards and Tom Carey, Canada Educational 10.1080/09523980410001680824 remi41304.sgm 0000-0000 Original Taylor 302004 41 Centre DianeSalter dianesalter@lt3.uwaterloo.ca 000002004 and & for Article Francis Learning (print)/0000-0000 Francis MediaLtd Ltd International and Teaching (online) Through Technology (LT3)University of Waterloo200 University Avenue WestWaterlooOntarioCanada N2L 3G1 Abstracts Current educational literature stresses the importance of a task-based approach to instruction, rather than an emphasis on content delivery. However, as institutions attempt to meet the demand for online courses, many offerings still focus on presenting online content resources with minimal opportunity for interactions and active learning. To help faculty with the complex problem of designing pedagogically sound online course components, the University of Waterloo developed an instructional design model, T5, to provide a shared campus-wide vocabulary for active learning online. The model is embedded as a gateway to existing Learning Management Systems (LMS); the model promotes the creation of a learning environment with a collaborative-constructivist approach to online learning. In this paper, we describe the components of this model and how the model promotes an integrated instructional approach, as well as the sharing of resources, between on-campus and distance education course delivery. In addition, we describe how faculty are guided in course development and delivery and the options available to provide faculty with different levels of engagement with the course delivery system. Le modèle de design T5 : un modèle d’enseignement et environnement de formation qui soutient l’integration de cours en ligne et sur le campus La littérature de formation récente accentue l’importance d’un approche basé sur les buts d’enseignement plutôt que de souligner la diffusion du contenu. Bien que les institutions essayent de répondre à la demande de cours en ligne, beaucoup d’offres ce concentrent toujours sur la présentation de ressources de contenu en ligne avec très peu de possibilités d’interaction et de formation active. Pour aider les facultés à créer des composants de cours pédagogiques efficaces en ligne, l’université de Waterloo a développé un modèle d’enseignement T5 qui prévoit un vocabulaire commun sur tout le campus pour la formation active en ligne. Ce modèle sert de portail au système de gérance de formation existant (LMS), et il encourage la création d’un environnement de formation avec un approche collaboratif et constructif de formation en ligne. Dans cet exposé, nous décrivons les composants de ce modèle et comment il fait progresser l’approche intégré d’enseignement ainsi que l’utilisation commune de ressources lors des cours de formation au campus et par correspondance. Nous décrivons également comment les facultés sont instruites concernant le développement et la diffusion des cours et quelles sont les options possibles pour soutenir Das T5 Unterrichtsmodell: Ein Lehrmodell und Lernumfeld zur Unterstützung der Integration von Online- und Hochschulkursen Die gegenwärtige Bildungsliteratur hebt eher die Bedeutung eines aufgabenbasierten Lehransatzes hervor als einen Schwerpunkt auf die Vermittlung von Inhalten zu setzen. Obwohl Institutionen versuchen, der Nachfrage nach Online-Kursen gerecht zu werden, konzentrieren sich viele Angebote immer noch auf die Darstellung von Ressourcen mit Online Inhalten, die nur sehr geringe Möglichkeiten der Interaktion und des aktiven Lernens bieten. Um Fakultäten bei diesem komplexen Problem zu helfen, pädagogisch wirksame Komponenten für Online-Kurse zu entwerfen, hat die Waterloo Universität ein lehrreiches Unterrichtsmodell T5 entwickelt, das einen gemeinschaftlichen, hochschulweiten Wortschatz für aktives Online-Lernen bietet. Dieses Modell dient als Portal zu bestehenden Lern-Management-Systemen (LMS); Es fördert die Bildung eines Lernumfelds mit einem gemeinschaftlich-konstruktiven Ansatz des Online-Lernens. In diesem Bericht beschreiben wir die Komponenten dieses Modells und wie es einen vernetzten Unterrichtsansatz und das gemeinsame Nutzen von Ressourcen für die Kursangebote von Hochschul- und Fernstudium fördert. Zusätzlich zeigen wir auf, wie Fakultäten in die Entwicklung und Vermittlung von Kursen eingewiesen werden und welche Optionen vorhanden sind, um Fakultäten mit unterschiedlich starkem Engagement mit dem Kursvermittlungssystem zu versehen. Educational Media International ISSN 0952-3987 print/ISSN 1469-5790 online © 2004 International Council for Educational Media http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals DOI: 10.1080/09523980410001680824 208 EMI 41:3 – DISTRIBUTED LEARNING PART 1 Introduction Increasing demand to incorporate technology into teaching has challenged both faculty and institutional systems. Faced with increasing enrolments and large class sizes, online resources are increasingly proposed as a way to expand on- and off-campus learning opportunities (Harley, Maher, Henke and Lawrence, 2003). Course redesign to incorporate an asynchronous online learning model has been used by institutions to reduce classroom space requirements (Bishop, 2003) as well as to provide opportunities for enhancing student learning (Bransford et al., 2001; Garrison, 2003). However, as institutions attempt to rapidly meet the demand for online courses, the quality of the online experience varies across, and often within, institutions. Many online courses still focus on presenting content online with minimal opportunity for interactions and active learning. Over the last 4 years an increasing number of faculty are using technology, but primarily for administrative and delivery functions. A survey of Canadian and American colleges and universities found that 69% of faculty used web content for lecture preparation, but only 15% used online group work for discussion to optimize learning outcomes (McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 2003). A good learning environment requires opportunities for interaction and feedback (Chickering and Ehrmann, 1996). Cognitive theorists describe how discussion and feedback promote learning through cognitive dissonance (Piaget, 1954; Festinger, 1964) as students confront and discuss conflicting opinions with peers. Many learning theories, such as constructivism, socially shared cognition and distributed learning theory, support the view that student learning is enhanced through opportunities to work collaboratively. Cognitive researchers today commonly test and refine these theories in classroom settings with important implications for educators (Bransford et al., 2001). The results of a meta-analysis of 122 studies involving 11,317 learners supported the benefit of online interactions to promote learning within a social context. However, historically, the most common use of computers by students is for individual work (Lou et al., 2001). The potential of computer technology to enhance learning outcomes will not be maximized without careful consideration of empirical research on learning and application of these principles to the design of the online learning environment. Evolution in thinking about online course design At a basic level, an online learning system can be seen as an information system. An online component in this view might include a course syllabus, class content material, resources relevant to the course (or direction on how to find content resources), as well as course lecture notes and power points. While the online system may be of some value to the student through the provision of easy access to course information, this limited experience provides no opportunity for the interactions possible in an online learning environment. Three kinds of interactions have been identified as important to learning in an online environment: interaction with content, interaction with instructors and interaction with peers (Moore, 1989). These types of interactions allow educators to move beyond simple replication of lecture delivery via the computer (Garrison, 2003). To facilitate deep learning (Van Weigel, 2002), the design of the online learning environment requires a shift in focus from content-delivery to a task-based instructional approach with opportunities for reflection and collaboration. Pointing the students to web-resources or online lecture notes is not enough. For students to develop an understanding of the course content, the online learning environment requires learning activities (tasks) to engage students with the content (Vella, 2000; Littlejohn, 2003). In a task-based approach, the learning tasks and feedback to the tasks serve as the primary vehicles for learning by engaging the student with the course content to solve the learning tasks. When developing an online course, instructors need to think about the instructional challenges and learning objectives specific to their courses and then introduce tasks to help students meet the learning objectives and overcome the instructional challenges. The following are common instructional challenges described by participants in Learning Design Faculty Series Workshops at the University of Waterloo: ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Students do not prepare for class time; Lab time is wasted teaching basic information; No time to cover topics in depth; No time for discussion in class; Bottlenecks – difficult concept to teach/learn – students need additional resources/practice; Difficulty in motivating student; Difficulty providing feedback to individual students in large classes; The ‘T5’ Design Model ● ● 209 Diversity of the student population in the class – i.e. range from strong background/major to no prior knowledge of this subject – require extra help/resources; and Students do poorly on tests/assignments without learning from the experience. By taking a task-based approach and incorporating interactions to promote student engagement with learning, institutions can move beyond using a Learning Management System (LMS) as an online information system. In this way, the potential of an LMS to add value as a broader reference support system will be realized. Some tasks may be designed as individual activities, allowing students to interact with the content of the course by reflective activities. Other tasks may require interactions with peers in the form of collaborative group work. Student-instructor and instructor-student interactions are possible by the use of online feedback to task submissions from the instructor to students about the tasks. Instructor feedback can be given to individual students or to the entire class. The feedback allows the students to assess their understanding of the course material and overcome instructional challenges prior to formal course evaluations. One key priority of an LMS is the presentation and management of the workflow for students and instructors. For example, assignments usually have several components. In a typical course, a student may have to write a report or prepare a research proposal; steps may involve identifying a topic, identifying sources, critiquing sources, developing a methodology and so on. Although students are provided with lists of expectations, feedback on their understanding of the assignment typically does not happen until the submission is presented for grading. Tasks and feedback during the formative process can help the students manage the workflow, help instructors know if the students are on track and help students perform better on the final assignment. Providing marks for learning tasks, based on completion rather than on correctness, encourages the students to complete tasks. Several courses at the University of Waterloo have been redesigned to incorporate tasks leading up to a formal assignment with marks for task completion incorporated into the total assignment mark. Instructors report that the rate of learning task completion was high and students generated a better quality final assignment, suggesting that tasks and feedback contributed to the improved final product. One example of how this approach was used is an information literacy task incorporated into an essay assignment to provide students with formative feedback regarding proper citation of sources for their assignment. Student feedback about this task was positive. In the course evaluation, many students commented that finally someone had taught them these basic search tools and bibliographical methods, as exemplified in the following student quote: I thought the task was a very good exercise. I often have difficulty finding the proper way to cite sources, but this showed me where to find resources that could help. Thanks! (Student comment on course evaluation feedback form) Another common instructional challenge for faculty is students’ lack of preparation for class time. Often, students attend class without completing the required readings. Therefore, even if an instructor attempts to provide an opportunity for in-class collaboration, the face-to-face discussion is limited; students have not prepared and lack sufficient understanding of the content to participate. The preparation level can be increased if students are required to complete an online task that requires them to engage with and think about the required reading. An example of a learning task requiring group collaboration that overcomes this instructional challenge is the following task used in an arts course (German Thought and Culture). The objective of the instructor was to introduce students to unfamiliar texts and engage in class discussions about the readings. However, most students did not read the assigned readings before class; consequently discussion in class was minimal. The instructor implemented a task that required students to prepare for class time by participating in an online discussion group (three students per group) to discuss a specific set of questions about the readings assigned for each week. The questions were designed by the instructor to encourage initial thinking about the text and highlight special points about the text (rather than ‘knowledge based’, right or wrong answer type of questions), followed by reflective online discussion. Each week, the group chose one member to assume the role of leader; the leader summarized the discussion and posted the response summary. The instructor reviewed the summary postings and could use points raised in the task submissions to incorporate into the following week’s lecture. The online discussion enhanced the quality of the in-class discussion. Again, most students responded positively to the use of tasks in the course, as expressed by the following student comment: I just wanted to say that I really think the pre-class activities are a great idea! By having these I feel motivated to read the essays. As well, the fact that we have to go online and work as a team on the internet, figuring out answers together is also something that I think is a really great idea. (Student comment on course evaluation feedback form) Another instructional challenge is limited instructor time for individual consultations. In an actuarial science course, the instructor designed a practice task that students were required to attempt before seeking additional help. Students attempt and submit the practice task online. Upon completion of the practice task, the student 210 EMI 41:3 – DISTRIBUTED LEARNING PART 1 receives online, pre-set, automatically generated feedback. If their answer is incorrect, they receive online feedback with guidance to help them evaluate and re-try the task. If, after the second attempt, the student is still experiencing difficulty, the student can use the submission tool to show the professor their work and seek individual feedback. However, students must attempt to solve the task and show their efforts to the instructor via the online submission in order to get assistance. This saves instructors’ time, as it is not necessary to respond individually to students’ first attempts at solving the problem. Some students will be able to solve the problem after they receive the generic/automatic feedback. This model of online feedback with guidance is useful in fully online Distance Education courses and in large on-campus classes where instructor time for individual student consultations is limited. Online guidance also helps alleviate the instructional challenges common in classes where the students’ background experience is mixed relative to their prior exposure to the course topics. By completing tasks and receiving online feedback, students can work independently and learn at their own pace. Feedback can be prepared ahead of time by the instructor and automatically generated for students to receive after completion of a task. The feedback allows the student to monitor and assess their level of understanding. Guiding faculty in course development and delivery Many institutions have taken the approach of introducing course management systems and providing technology training to faculty on how to use the learning management system (LMS). This traditional approach of separating technology from teaching application has limited success. Most university professors have limited formal training in how to teach or how to design an effective learning environment (either face-to face or online) and tend to follow the model they have experienced, that is the traditional lecture delivery of course content. Often faculty spend considerable time learning the LMS or individual tools and struggle to make the connection on how best to use the technology in their course. Most ‘off the shelf’ LMS products focus solely on the technology options, such as setting up class discussions or providing quizzes and have no pedagogical framework to help faculty to use the technology to create the learning environment. Commonly used delivery platforms also tend to separate the required online activities by function such as quizzes or discussions rather than integrating the tasks with the related course content (Swan, 2003). At the University of Waterloo, we developed a pedagogical model (T5) to provide a framework for course development and delivery; however, even with the model in place, faculty need help in targeting the instructional challenges in their own course and in designing the appropriate tasks and feedback to incorporate throughout the course. Our goal was to introduce faculty to the T5 model and provide scaffolding to help faculty achieve success in adopting the model. The approach we took was to provide: ● ● ● A simple instructional model (T5) that could be incorporated for an online or in class setting; Faculty workshops (Learning Design Faculty Series) to help faculty: — understand the model, — develop ideas for tasks and feedback to use in their own course to meet specific course objectives, — receive individual and peer feedback during the coaching sessions and in online modules, and — scaffold faculty transition of course re-designs from concept to development; and A pedagogical gateway to existing LMS systems, designed around the T5 model. Components of the T5 model: an integrated instructional approach The T5 model was developed as an approach to instructional design that emphasizes Tasks (learning tasks with deliverables and feedback), Tools (for students to produce the deliverables associated with the tasks), Tutorials (online support/feedback for the tasks, integrated with the tasks), Topics (content resources to support the activities) and Teamwork (role definitions and online supports for collaborative work). Learning tasks require students to engage with the course content to produce a deliverable artifact. The deliverables and feedback to these deliverables are the primary vehicles for learning. The guiding principles, in the design of the T5 model, include flexibility to allow for re-use of the many learning objects, defined as any digital resource that can be re-used to support learning (Wiley, 2000), that have been developed and can be incorporated into the model. The development of learning objects and digital repositories is expanding. As new learning management systems are developed, a consideration of how new technologies can facilitate the sharing of resources is an important element. The goals for the T5 design model include: ● ● Assume/embed re-use of learning objects; Maintain faculty ‘ownership’ of learning design; The ‘T5’ Design Model ● ● ● ● ● ● 211 Scaffold transition from concept to design; Focus on learning activities, supported by content; Provide a model suited to on-campus (classroom based) and online courses; Encourage rethinking of learning process and roles; Increase Results Oriented Instruction (ROI) through learning productivity; and Emphasize performance support, not information system. The concept of this model has been central in guiding faculty to think about how to design and incorporate tasks and feedback into their courses, as described in the task examples in this paper. Faculty workshops: how faculty are introduced to the University of Waterloo online environment (UWone) Many institutions have invested heavily to provide a technology infrastructure to support learning. However, the greatest challenge when introducing technology is in the training of faculty in how to use these technologies (Epper and Bates, 2001). We designed a program for faculty, The Learning Design Faculty Series, that models the task-based instructional approach that faculty will use in their own courses. By participating in the series using the University of Waterloo Online Learning Environment (UWone), faculty learn about the T5 model of student-centred instruction and experience how technology options can provide a deep learning experience concurrently with the preparation of their own course template. Faculty consider technology options to address their specific instructional challenges by participating in a combination of online activities and face-to-face coaching sessions. Support is provided to scaffold faculty transitions from the conceptual design of their course to the actual resource preparation as they develop an online component for the course they teach concurrent with participation in the series. To overcome the challenges commonly described in attracting faculty to participate in workshops, we gave careful consideration to the time commitment faculty would make and the deliverable they would produce during the workshop. We offer none of the commonly offered incentives (such as monetary stipends, free books or food); the reward comes in having the initial content free template for their course set-up and the creation of a few well thought out, course specific, task and feedback ideas that the instructor articulated during the series. Following the workshop, coaching is provided from the faculty liaisons on staff at the Centre for Learning and Teaching Through Technology (LT3) to help implement the task and feedback ideas. An LT3 Liaison is assigned to each faculty (Arts, Science, Environmental Studies, Mathematics, Engineering, Applied Health Sciences) at the University of Waterloo as a point of initial contact for faculty who are interested in technology innovations and also to offer support in developing and implementing the task and feedback ideas generated in the faculty series. Many institutions separate instruction in curriculum design from instruction in innovations in learning technology or distance technology from pedagogy by providing technology options before identifying instructional objectives and challenges. Most instructors have not participated as a student in a course with an online component and therefore have no model, derived from their own past learning experiences, for integrating technology into a course. Although faculty may be interested in learning about teaching and technology options, most have limited time to spend learning complicated technology. To help overcome these challenges, our goals for the delivery method created for the Faculty Series were: ● ● ● To focus on curriculum design issues, integrating the use of technology tools during participation in the series; To provide an authentic setting (learning in the same context the learning will be applied) for the faculty members to learn about the online technology options; and To provide flexible timelines for completing the required components. To provide an authentic learning experience, material is introduced in the same context that the learning will be applied. Faculty participate as students to work through the online modules of the course content and in the coaching sessions. Provided online are the necessary Topics; these include suggested readings, recorded lectures and other support material. The Tools provide the resources to help faculty complete and submit their online Tasks. Feedback and Tutoring is provided online and in the coaching sessions. Concurrently, participating as an instructor, faculty develop an online course template for their course. This helps to engage the participants with the learning support system that they will use to build, deliver and manage their own course. The series usually takes place over a 4-week period as follows: 212 EMI 41:3 – DISTRIBUTED LEARNING PART 1 Week 1: Complete four online modules in preparation for Coaching Session A (3–4 hours online) Module 1: Orientation. Module 2: Introduction to the T5 model. Module 3: Learning theories/learning and teaching with technology. Module 4: Designing learning tasks. Week 2: Module 5: Coaching session A: Attend coaching session (2 hours face-to-face). Week 3: Complete two online modules (3–4 hours online) and refine task ideas discussed in coaching session A in preparation for Coaching session B. Module 6: Designing feedback. Module 7: Expanding time and space. Week 4: Module 8: Coaching session B: Attend coaching session (2 hours face-to-face). During the coaching sessions, participants describe their self-generated instructional goals and challenges and discuss technology options that may help with these challenges. The focus of coaching session A, as well as the related online preparatory modules, is on the design of learning tasks. The focus of coaching session B and the second set of online modules is the type of feedback options faculty can use to provide feedback to their students. In addition, faculty are encouraged to ‘re-think’ the use of classroom time and homework time when incorporating an online component. An important part of the coaching session is the dialogue between participants; this allows them to clarify misconceptions about using online technologies, describe preliminary ideas for tasks, receive feedback to help in developing these ideas and discuss best practices. In coaching sessions, the coach/facilitator ensures that new ideas are fully understood so that they can be incorporated into practice. Faculty sometimes come to the series to learn about how to use technology options to set up a web-site or a discussion, but may have a limited understanding of how, or why, to provide an online learning environment with opportunities for collaboration and reflection. By completing the online modules in the Learning Design Series, instructors are guided to first think about their instructional objectives and challenges. Sometimes faculty enter the series with a focus on learning the technology; however, we have consistently noted that participating in the series evokes re-thinking the design and delivery of their own course material. The following faculty comment describes this shift in thinking: Prior to engaging in this course, I was simply looking for a quick and easy solution to mounting a few handouts, assignments and old exams on a web-site. Students in previous course evaluations had requested this. … When I was first exposed to the T5 learning modules, I felt that I was being led along a path that was quite different from my initial goal. I was forced to examine my teaching at a very fundamental level, essentially dealing with the philosophy of teaching and the underlying principles of learning. This lead to some initial irritation and resistance on my part as I felt my established classroom teaching methods (which until now had been moderately successful) were being threatened. … After the coaching session A, I began to overcome my own resistance and initial aversion to the T5 model. I was able to look at the creative potential of adopting the T5 methodology to core engineering courses and using some of the new e-learning tools being offered within the T5 framework of person-centered learning. I expect these insights to lead to better learning opportunities for my future students. (Personal e-mail, Engineering faculty member, following The Faculty Series, November 2002) The faculty series was first offered in November 2001. Since then, 196 participants, representing all of the University of Waterloo faculties (Arts, Science, Environmental Studies, Engineering, Mathematics and Applied Health Sciences), have participated. Table 1 depicts the numbers of participants, identified by role and department. At the end of the second coaching session, participants complete an evaluation form. Analysis of this feedback shows a high level of satisfaction with the time frame and the practicality of the sessions. The following faculty comment is typical: I found the workshop very informative. I left leaving with ideas and means to try an online component. (Comment on Feedback form following coaching session B, faculty member, Applied Health Sciences, November 2003) Faculty are immediately able to apply their ideas about tasks and feedback into their course design. Support following the workshop (pedagogical guidance from the LT3 liaisons and technical support from a co-op student) is available to help the faculty member implement their task and feedback ideas into a reality. Formal tracking studies are currently underway to monitor how faculty have implemented tasks and feedback into their courses. Faculty are also including questions about the use of tasks and feedback into course evaluations so that student feedback can be recorded. Formal learning impact studies of these activities at the University of Waterloo are underway. We have also adapted and delivered the series internationally, including institutions in Thailand, Hong Kong and Sri Lanka. By incorporating the learning of technology options with sound pedagogical practice, faculty 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 7 1 4 2 3 4 3 3 4 Eng (17) 5 AHS (26) 1 1 2 11 3 8 1 12 15 Arts (55) 1 1 1 4 4 ENVS (11) 1 1 3 1 3 1 Math (10) 1 3 2 1 2 DE (15) 1 7 1 13 Lib (14) 1 1 3 2 2 1 4 7 4 3 Sci (30) 1 1 2 1 1 3 3 LT3 (12) 1 IST (1) 1 2 2 Other (5) Total participants: 196; Teaching role: 156; Teaching support role: 40. Arts = Faculty of Arts; AHS = Faculty of Applied Health Science; Eng = Faculty of Engineering; ENVS = Faculty of Environmental Studies; Math = Faculty of Mathematics; Sci = Faculty of Science; Lib = Library; DE = Department of Distance Education; IST = Information Systems and Technology; LT3 = Centre for Learning and Teaching through Technology. Teaching support (40) Instructional Designer (4) Instructional Developer (10) Instructional Research (2) Instructional Manager (5) Educational Consultant (3) Visiting Instructional Developer (2) LT3 Faculty Liaison (6) Instructional Coordinator (3) Instructional Planner (1) IT Support (4) Teaching role/title (156) Full Professor (21) Professor Emeritus (1) Associate Professor (32) Assistant Professor (29) Adjunct Associate Professor (1) Adjunct Assistant Professor (2) Lecturers (37) PhD Student (3) Instructor (4) Lab Instructor (6) Lab Demonstrator (2) Lab Coordinator (1) TA (teaching) (8) Visiting Professor (5) Research Associate Professor (2) Research Assistant Professor (1) Student Lecturer (1) Number of participants by faculty and title Table 1 Participants in the Learning Design Faculty Series October 2001–November 2003 The ‘T5’ Design Model 213 214 EMI 41:3 – DISTRIBUTED LEARNING PART 1 have been able to reconsider the design and delivery of their courses and move beyond replicating lecture content in an online environment (Salter, Richards and Carey, 2003). Developing a pedagogical gateway: how the course delivery platform supports the model As described earlier in this paper, many institutions have introduced learning management systems and provided technology training on how to use the system. However, ‘off the shelf’ LMS products often focus on the technology options and lack a pedagogical framework to help the faculty use the technology to create a rich learning environment. In addition, LMS products lack support tools for implementing the types of tasks and feedback activities described in this paper. To help faculty with the complex problem of designing an online course, the University of Waterloo created a gateway (UWone) to an existing learning management system (ANGEL/Cyber Learning Labs) as well as access to in-house tools. In-house tools, created at the University of Waterloo, include the Workflow Manager, the Teamwork Tool and the Learning Design Tool. These tools help instructors to create and deliver the types of task and feedback options described in this paper. The Workflow Manager allows instructors to create and manage different types of task submissions and different feedback options to these tasks. The Teamwork Tool allows flexibility in setting up teams and team activities and imbeds the necessary tools for completion of teamwork within the activity. The Learning Design Tool allows instructors to build their course within a contentfree framework based on the T5 model. The gateway (UWone) provides a common framework for thinking and talking about how to design an online component to a course and forms the basis of the University of Waterloo online learning system for both mixed-mode, on campus courses as well as fully online distance education courses. The course development and delivery platform (UWone), based on T5, serves to guide the instructor in both the design of the learning space and the delivery of the course. Using the framework provided by UWone, instructors can easily incorporate Topics, Tasks, Tutoring and Teamwork into the instructional design of the course. As comparable products become available, commercially we will be able to incorporate those components into UWOne and remove ours. Another component currently in development is the Course Mapper. The goal in developing the Course Mapper is to guide faculty as they re-think the design of a full course. Faculty will be able to enter their course syllabus, identifying content and evaluation components and code the content for learning objectives, difficulty level and instructional challenges. The Course Mapper will help faculty to identify appropriate times to incorporate learning tasks into the course to assist students with instructional challenges. We have piloted the Course Mapper process on paper in the re-design of several courses. In addition, we are experimenting with standardscompliant representations for designs of learning tasks (using IMS Learning Design specifications); this will allow faculty to more easily identify existing identify existing Learning Designs (LD) and Learning Objects (LO) that can be incorporated into the course. This will facilitate sharing of resources between universities by the ability to search repositories, such as MERLOT (1997–2003) and CLOE (Co-operative Learning Object Exchange, available online at: http://cloe.on.ca) for re-usable content resources. Sharing of resources between on campus and distance education courses: rethinking the use of time and space The design and learning environment, based on the T5 model, guides the instructor in the design of the learning activities, supports re-use of resources and helps make the instructional design and rationale apparent to the students. Instructors developing online courses with the T5 Design Model have noticed how online resources facilitate student learning. Consequently, by incorporating their online resources into blended oncampus courses, a merging of instructional approaches in online and on-campus courses has occurred, leading to a ‘re-thinking’ of the possible uses of in-class time and out-of-class time. As well, on-campus instructors, who also teach distance education courses, are interested in incorporating the task-based model into their distance courses to provide more interactivity for the distance students. Subsequently, a number of faculty teaching oncampus courses are experimenting with ways to incorporate an online component and change their use of inclass time to reduce the dependency on the typical lecture model. In the typical lecture class model, the instructor generally directs class time for 90–100% of the time. However, a great deal of research shows that the lecture, although widely used, is not an effective way to create deep learning or creative thinking (Van Weigel, 2002) and provides little more than an information transaction (Bligh, 1972). Online tasks provided prior to class allow the students to engage with the content ahead of time; in-class time can then be re-directed to incorporate meaningful discussion with feedback on the pre-class tasks (Novak, 1999). The ‘T5’ Design Model 215 A good example of this change in use of class time is provided by the changes incorporated into a large oncampus accounting course. In this course, student-instructor interaction is facilitated by a 1-minute summary (OMS) task that allowed a ‘re-thinking’ of the use of classroom and homework time. The instructor had successfully used the OMS tasks to receive feedback from students in his fully online course and wanted to incorporate the use of the OMS in his on-campus course. The 1-minute summary was introduced by the instructor as a way to change the in class lecture time to focus on students’ misconceptions and questions about the module of study. Students were directed to review the lectures online and complete a 1-minute summary before face-to-face class time. Questions posed in the OMS required students to demonstrate an understanding of the topic (by preparing a multiple choice question about the content) and to ask questions that they would like the instructor to address in class. The instructor could then use class time to address student concerns as identified in the 1-minute summary. To manage the large class size of 800 students, 10 TAs were assigned a unit of 80 students each. The TAs scanned the student responses (using the Workflow Manager tool described in this paper). Each TA prepared a 1-minute summary to summarize the questions and comments of his/her group of 80 students. The instructor reviewed the 10 1-minute summaries from the TAs in preparation for the face-to face lecture. The instructor was then able to modify his traditional lecture to respond to student misconceptions and questions identified in the 1-minute summaries. An on-campus economics course also piloted ways to change the use of in-class time by incorporating resources originally created for a distance education (DE) course. The on-campus course involved 9 hours of lecture a week (three classes, each 3 hours in length). The instructor found that the CD-ROM created for the DE students provided rich resources for students about the course material and wanted to provide the on-campus students with the same resource. However, recognizing the need to integrate the use of the CD with the oncampus course delivery, rather than as an ‘add-on’ to the work-load, the instructor changed the use of class time as well as students’ use of homework time. To pilot the use of incorporating the CD with the on-campus students, two classes each week followed the traditional lecture format, but the third class was made an ‘optional attendance’ class devoted to responding to questions students had about homework exercises that they had completed using the CD resource. Entry levels to UWone The UWone system is designed to give maximum flexibility and control of the course content and design to the instructor. Although the system is grounded by a pedagogical framework without an understanding of why and how to use the model, this flexibility can lead to misuse and the creation of a confusing learning environment. To avoid overuse of tasks and dissatisfaction among students and instructors, faculty considering technology options are encouraged to participate in the Learning Design Faculty Series. Participation in this series allows instructors to learn how to make full use of the online environment by providing tasks and feedback, using automatically generated feedback to avoid increasing instructor workload, using online conferencing tools, developing quizzes and providing multiple ways for students to interact with the course content resources to meet instructional challenges. Workshops on ‘re-use’ options, to provide faculty with information about re-usable Learning Objects and Learning Design resources, will become increasingly important as repositories for learning objects and ways to share resources expand. As well, ‘Skills Facilitation’ workshops are offered to provide training in how to provide online feedback and facilitate discussion. A ‘Course Mapper Workshop Series’ is in development and has been piloted with individual faculty members who wish to consider the redesign of their full course to incorporate online components. Conclusions/future directions At the University of Waterloo we have made an effort to provide a pedagogical gateway, through the University of Waterloo Online Learning Environment (UWone), to promote the development and delivery of courses with a collaborative-constructivist approach to learning. Early LMS systems did not provide the tools to create the types of tasks and feedback our instructors wanted to create in their courses; this led to the development of in-house tools to meet these needs. However, the providers of vendor supported LMS systems are now entering a dialogue to work collaboratively with institutions to create and develop the next generation of LMS systems with tools to support active learning. The use of UWone has led to a crossover of resources and approaches to course re-design between on-campus and distance education courses. Most university faculty have no prior training in course design or how to teach, 216 EMI 41:3 – DISTRIBUTED LEARNING PART 1 as typified in the following comment: ‘I’ve had no formal training in teaching. I was just supposed to know how to do it, somehow’ (Faculty e-mail comment, 2002). Faculty typically begin their exploration of online technology options with limited ideas about the possibilities for creating an interactive online component. The following comment, completed as a ‘1-minute summary’ task for the orientation module to the Learning Design Series, describes a change in thinking about how to use technology options, following an introduction to UWone: One minute summary question: How are the ideas reviewed in this module relevant to you as you develop an online component to your course? Faculty response: I came to the site (the Learning Design Series course site) thinking that my main goal was to learn how to use the technology. Now I wonder whether there’s more to this – not just knowing how to put together a web page, but to put together the right page to accomplish your (instructional) goals. (October 2003) The institutional trend to incorporate online learning environments as standard practice provides a unique opportunity for faculty to explore options on how to deliver their own course. Based on the model of course delivery faculty know from their own classroom experiences, faculty generally choose the lecture for almost all teaching situations, even if they describe their own best learning experiences as interactive. If we hope to encourage faculty in producing online courses that go beyond a replication of lecture content online, it is essential that institutions provide support in terms of an online learning system with a pedagogical framework, tools to promote active learning online and training to scaffold course development. References Bishop, T (2003) Linking cost effectiveness with institutional goals: best practices in online education. In Bourne, J and Moore, JC (eds) Elements of Quality Online Education: Practice and Direction, 4, Sloan-C Series, pp. 75–86. Bligh, DA (1972) What’s the Use of Lectures? Penguin, Harmondsworth. Bransford, JD, Brown, AL and Cocking, RR (2001) How people learn: brain, mind, experience and school, National Academy Press, Washington, DC. Available online at: http://www.nap.edu, accessed 12 December 2003. Chickering, A and Ehrmann, SC (1996) Implementing the seven principles: technology as a lever, AAHE Bulletin, October, 3–6. Available online at: http://www.tltgroup.org/programs/seven.html, accessed 12 December 2003. Epper, RM and Bates, AW (2001) Teaching Faculty How to Use Technology, Oryx Press, Westport, CT. Festinger, L (1964) Conflict, decision and dissonance, Stanford Studies in Ppsychology, 3, 7, 163. Garrison, DR (2003) Cognitive presence for effective asynchronous online learning: the role of reflective inquiry, self-direction and metacognition. In Bourne, J and Moore, JC (eds) Elements of Quality Online Education: Practice and Direction, 4, Sloan-C Series, 47–58. Harley, D, Maher, M, Henke, JN and Lawrence, S (2003) An analysis of technology enhancements in a large lecture course, Educause Quarterly, 3, 26–33. Littlejohn, A (2003) Reusing Online Resources, Kogan Page, London. Lou, Y, Abrami, PC and d’Apollonia, S (2001) Small group and individual learning with technology: a metaanalysis, Review of Educational Research, 71, 3, 449–521. McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited (2003) Technology & student success in higher education: A research study on faculty perceptions of technology and student success, Toronto: McGraw-Hill. MERLOT (Multimedia Educational Resources for Learning and Online Teaching) (1997–2003) Available online at: http://www.merlot.org accessed 31 January 2004. Moore, MG (1989) Three types of interaction, American Journal of Distance Education, 14, 2, 1–6. Novak, G (1999) Just-in-time teaching: Blending active learning with web technology, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Piaget, J (1954) The child’s construction of reality, Basic Books, New York. Salter, D, Richards, L and Carey, T (2003) A task-based approach to integrate faculty development in pedagogy and technology, Elearn. Swan, K (2003) Learning effectiveness: what the research tells us. In Bourne, J and Moore, JC (eds) Elements of Quality Online Education: Practice and Direction, 4, 13–45. University of Waterloo (2003) The Learning Design Faculty Series. Available online at: http://lt3.uwaterloo.ca/ faculty, accessed 19 December 2003. Van Weigel, B (2002) Deep learning in a digital age, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco. Vella, J (2000) Taking Learning to Task, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco. The ‘T5’ Design Model 217 Wiley, DA (2000) Connecting learning objects to instructional design theory: a definition, a metaphor, and a taxonomy. In Wiley, DA (ed.) The Instructional Use of Learning Objects: Online Version. Available online at: http://reusability.org/read/chapters/wiley.doc, accessed 19 December 2003. Biographical notes Diane Salter is Dean, Centre for Curriculum and Faculty Development, Sheridan College Institute for Technology and Advanced hearing. She was formerly an Assistant Research Professor at the University of Waterloo and is the lead on the Faculty Program at the Centre for Learning and Teaching Through Technology (LT3). Dr Salter is a specialist in learning and teaching in higher education with a background in cognitive science and educational psychology. Leslie Richards is the Senior Advisor, Instructional Technologies in the Centre for Learning & Teaching Through Technology (LT3) at the University of Waterloo. He also is the functional architect for the University of Waterloo’s on-line learning environment. Tom Carey is a Professor of Management Sciences and Associate Vice-President for Learning Resources & Innovation at the University of Waterloo. Dr Carey also has leadership roles in several higher education collaborations for online learning resources. Address for correspondence Dr Diane Salter, Centre for Curriculum and Faculty Development, Sheridan College Institute for Technology and Advanced Learning, 1430 Trafalgar Rd, Oakville, Ontario L6H 2LI, Canada; e-mail: diane.salter@sheridanc.on.ca