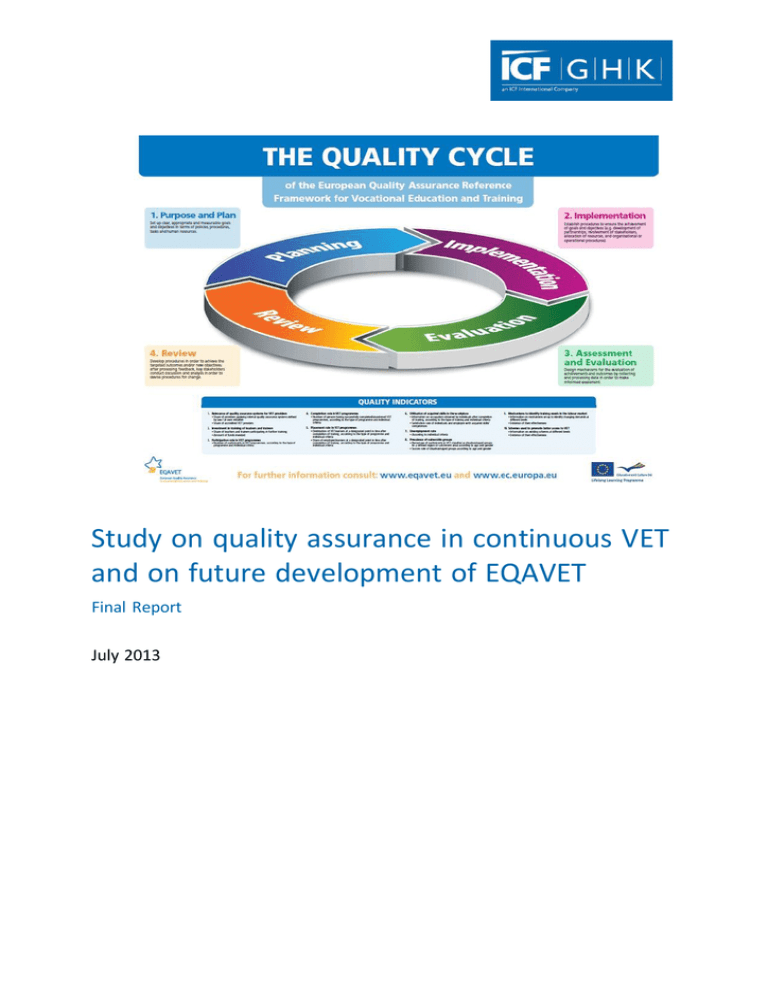

Study on quality assurance in continuous VET and on

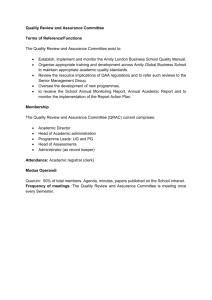

advertisement