The Natural Gas Paradox

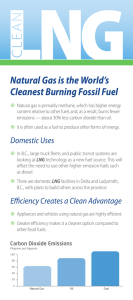

advertisement

Ladies and gentlemen! These are interesting times for the global natural gas industry. Over the past decade, technology and investment have shown us the path to unlocking and utilizing the vast abundance of natural gas trapped beneath our planet’s surface, on land and at sea. These capabilities arrive at a fortuitous moment as we move forward, however slowly, from the legacy energy sources of coal and oil and their numerous shortcomings to a more environmentally-benign and secure global economy. 1 The benefits of new energy technologies are appreciated most keenly by economic planners in the developing world, where a burgeoning middle class continues to drive improvements in living conditions that, in turn, are driving energy demand. There, the economic progress of two centuries of industrialization and urbanization built on coal and oil in the West has been compressed into two decades. In so doing, hundreds of millions of people have flocked to sprawling urban centers and found economic opportunity, creature comforts and the empowerment of personal mobility. Accommodating this massive shift has required expediency using energy supplies that are cheap and readily available. But as high-rise towers have gone up, cars and trucks have rolled off assembly lines and coal-fired power plants and oil refineries have proliferated, their unwelcome and unanticipated consequences have mushroomed in the form of rapid land and water quality deterioration, smog-choked skies and the financial strain of skyrocketing oil import bills. For these government and industry planners and the billions they serve here in Asia, but also South America, Africa and even the Middle East, the natural gas and LNG revolution now in full progress is just short of a miracle: A source of heat, power and transportation that is clean, plentiful and reasonably-priced; An energy source that is readily available on global markets today; and An energy source that has accessible reserves to provide stable and secure supplies well into the future. The International Energy Agency, surveying this scene, pronounced last year that the world economy might be at the cusp of The Golden Age of Gas, if certain impediments don’t persist. What are those impediments? Well, they can largely be found in the government institutions and popular media of the Western industrialized democracies, which have long enjoyed the benefits of natural gas in their energy mix. In the United States, natural gas is labeled as just another dirty hydrocarbon in many quarters, barely preferable to much more polluting coal and oil. In Europe, it is labeled not only dirty, but foreign. Natural gas is not dirty, and Europe has never before had so many alternative sources of supply. These perceptions are the source of misguided policies and commercial confusion in the European gas market today. These often-conflicting policy goals, and the uncertainty they generate, are threatening the orderly and efficient transition to broader utilization of natural gas, and all its numerous benefits, in European society. The crux of conflict in these policies can best be summarized by their contradictory premises: Natural gas is a clean and abundant fuel that can be reliably supplied day-to-day by numerous global competitors; but Natural gas must be eliminated from the European energy mix with all due speed. These policies, and their unfortunate manifestations, are the topics of my remarks today. These are not only very interesting times for the natural gas industry, they are exceedingly complex times as well. We are now moving towards a future which presents us with a range of urgent and critical energy challenges, many of which have yet to be fully understood. This fundamental shift has been brought about by a number of factors, one of which is the disappearance of relatively accessible and inexpensive oil reserves, the kind that helped power many of the economic achievements of the past century. 2 The world still holds large reserves of oil, but the supply of easy, inexpensive oil cannot keep pace with soaring demand in developing economies. The vast majority of what remains is harder to reach and more difficult to extract and process. In simple terms, this means that every barrel produced will be more expensive to the consumer. And keep in mind that this doesn’t even account for the enormous potential hidden costs associated with environmental disasters such as we saw two years ago with the Deepwater Horizon, not to mention the military and diplomatic costs of keeping critical supply lines open and secure. On the demand side, we see unprecedented growth in energy consumption in developing nations such as China and India. In fact, over 90% of demand growth in the next few decades is expected to come from countries like India, China and Brazil, while the market share of developed economies steadily declines. As energy consumption patterns evolve, so too does the role that different fuels play in the world's energy mix. The declining importance of oil, notably in power generation but increasingly even in transportation, is becoming more discernible. As the developing world continues to draw more heavily on world oil reserves, the search for long-term solutions to energy supply security and pricing stability will only intensify. Now contrast the outlook for oil with that of natural gas. Until recently there was broad consensus that global natural gas production was on the same trajectory as oil, just deferred a decade or two. Economies around the world, led by China, were expected to continue requiring greater amounts of energy to fuel their growth. Meanwhile, natural gas production in the West was thought to be in permanent decline, leading to premature assumptions regarding the long-term dependence of developed nations on imported sources of fuel. 3 The world, however, is not running out of gas. The new reality in global energy markets is one of plentiful, economic and diversified supplies of natural gas far into the future. Global proven reserves now stand at their highest on record at 190 Tcm, and last year the global reserves replacement ratio reached 220%. Industry and world leaders are just beginning to recognize and accept this fact. Even the IEA, an agency originally founded as a guarantor against physical disruptions in the global supply of oil, recently released a report supportive of a future “golden age of natural gas.” The report presents a scenario in which the global use of gas rises by more than 50% from 2010 levels to account for more than a quarter of global energy demand by 2035. 4 In fact, the consensus among most consulting firms, energy companies and research agencies is that natural gas will play an increasing role in the future energy mix, far outpacing coal and oil. I truly believe that this age of natural gas is upon us. Recent developments have created considerable opportunities for the increased use of natural gas globally and, as we shall see, in Europe especially. The simple reason for this is the fact that no other energy source today offers the combination of benefits that natural gas can to meet the world’s needs for clean, reliable and inexpensive energy. For these reasons, natural gas should - and will - no longer take a backseat to coal, oil and nuclear. However, throughout most of Europe, this simple fact is being ignored, and short-sighted policies are being implemented that discourage all forms of hydrocarbon use in preference to heavily-subsidized renewable energy, such as we have seen with the EU Roadmap 2050, which aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80%-95% [over 1990 levels] by 2050. In brief, the Roadmap promises a de-carbonized, competitive, and secure energy system for Europe, with lower energy costs and improved supply security. But are these goals realistic given the paths that are being proposed by the European Commission? In my opinion, the answer is unequivocally “no.” The Roadmap offers several scenarios for achieving its greenhouse-gas reduction goal, each incorporating a different degree of reliance on energy efficiency, renewables, nuclear power and carbon capture and storage, or “CCS”. CCS and nuclear generation would have to contribute significantly in most scenarios, with a share of between 19% and 32% of primary energy demand for CCS and up to 18% for nuclear generation. Public support for this level of build-up is unrealistic given the recent moratoria and planned phase-out of nuclear power generation in Germany, Switzerland and elsewhere. Carbon sequestration is still an early-phase technology, and subsequently should not be counted on to achieve EU emissions reductions goals prior to 2030. In this time period, natural gas is a better instrument to achieve EU Roadmap goals. After 2030, CCS may very well be a developed technology that can be used more widely to achieve the EU’s targets. The Fukushima nuclear reactor failures last year have again elevated public concern and political action against nuclear power, leading to government actions to constrain or even eliminate reliance on this major carbon-free source of baseload electric power. Without nuclear and fossil fuel-fired power generation, it is simply not possible to maintain the sufficiently reliable and flexible power grid that forms an essential foundation of both economic output and social comfort that is expected by most Europeans. Further, the Roadmap does not take into account financial constraints within the energy sector (or even within the EU economy) that could limit investment capabilities and reduce government subsidies for renewables; nor does it take into account the fact that reliance on new technologies can result in significant unanticipated costs. It is therefore highly unlikely that the solutions proposed by the Roadmap will result in any tangible cost benefit for the majority of Europeans and in fact may prove to be disastrously expensive. Perhaps as significantly, all five of the Roadmap scenarios assume that large reductions in primary energy demand – up to a 41% decrease over 2005/2006 levels – are needed to meet the EU’s greenhouse-gas reduction targets. While improved energy efficiency is both necessary and expected, achieving this level of reduction in overall energy demand is entirely unrealistic and would have an adverse effect on quality of life. Basing the success of the EU’s greenhouse gas reduction targets on it is a recipe for failure. The fundamental problem with the Roadmap is that it is built on the premise that only carbon reduction really matters, despite the technological challenges and social, economic and geopolitical risks this singular goal may entail. It is quite easy to conclude from this that, while the Roadmap claims to recognize the importance of costeffectiveness and supply security, it does not provide a concrete plan for incorporating these elements into European energy policy. In fact, what we are instead seeing in the European political arena is a complete divergence in energy policy, where the clean energy ‘ideals’ proposed by the EU Roadmap remain the official party line while there is considerable – and growing – internal discord in terms of policy implementation at the individual member state level. We have seen this recently with the moratoria on nuclear development that has been approved in several states in Europe and the differing paths taken by European nations in regard to shale gas development – with France and Bulgaria banning the practice, on the one hand, and Poland and Ukraine embracing it, on the other. What this situation has led to is growing energy policy paralysis and confusion, and an inability to take or even consider more appropriate actions on behalf of energy security and the environment. We can all agree that energy sector transformation is needed to reduce emissions and provide for a more secure and sustainable future. However, the scenarios proposed by the EU do not provide a true plan for doing so and do not fully account for the substantial cost savings and emissions reductions that are possible if natural gas is more widely adopted. The singular goal of drastic carbon emissions reductions by all means necessary is a recipe for long-term decline in living standards and the overall EU economy. It provides no way out of the current debt crisis, and instead expands the demand on national budgets to pay for financially unsustainable investments. At some point, this path will become politically impossible, and the carbon reduction goals will need to be relaxed to better balance the many competing objectives of energy policy. The only question is how much time and money will be wasted pursuing an ill-founded aspiration before political and economic reality shatters that dream. 5 What we need instead is a definitive plan with attainable results, one that offers the guarantee of reliable energy supply at the least cost to consumers and that relies on demonstrated measures for carbon reduction. While this plan would include renewables technologies, energy efficiency and conservation investments, natural gas would also be an essential component of that plan, premised on energy system evolution rather than a massive bet on a supposed revolution. A plan built around coal and oil substitution in the power, residential and transportation sectors using natural gas will enable the EU to quickly and steadily reduce CO2 while maintaining living standards and prospects for economic growth. As importantly, this plan would result in total cost savings of over €1.1 trillion for the EU. 6 For example, through the year 2030, employing a strategy of fuel-switching to natural gas in the power sector would meet projected increases in demand while achieving the required emissions cuts and reducing overall power costs by up to €500 billion. This is because natural gas is expected to remain one of the most cost-competitive alternatives for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. After 2030, it would be logical and economical to use natural gas-fired plants both as a source of baseload generation and to provide the necessary back-up generation for a growing portfolio of intermittent renewable energy sources. It is estimated that continuing this gas-focused scenario from 2030-2050 could avoid up to €400 billion in capital costs while total power costs would remain equal to or slightly better than the pathway projected in the EU Roadmap over this period. 7 Similarly, utilizing natural gas as a substitution for coal and oil in the residential sector would result in significant cost savings and positive environmental results. A gas-focused scenario (meaning ~30% of the fuel mix is comprised of natural gas) could save the EU up to €550 billion by 2050, while resulting in a 30% reduction in total carbon emissions. By focusing more on gas and less on immature or controversial technologies, the proposed plan would be less reliant on winning public or political support for massive investment in nuclear generation and expansion of transmission capacity. Instead, Europe would make use of its existing natural gas distribution network and of mature and flexible technologies that are relatively easy to implement. This would also mean that renewables and CCS can be phased in, with the greater share of investments taking place when the technologies themselves are more mature, leading to a smaller overall investment requirement. In fact, my company analyzed several emissions-reduction plans and concluded that despite the publicity accorded to the EU Roadmap and its dismissive attitude toward natural gas alternatives, the overwhelming consensus is that demand for gas will increase from current levels. This is an encouraging sign that clean-burning, abundant and reliable natural gas can become the fuel of choice in meeting future demand growth. One of the main reasons for this optimism is the growing realization that renewable energy resources are not scalable to a level that will enable Europe (or the world) to meet its carbon emissions reduction goals. Intermittent power supply is already a significant issue in parts of Europe (such as Denmark), and adding a large share of non-intermittent and load-following generation from natural gas will make the power system significantly more robust, contributing to a more reliable energy supply. Gas generation is not only a necessary complement to intermittent wind and solar generation due to its quick start-up time and reliable operations, but it also provides an economical source of baseload power, given that natural gas has the highest reliability compared with other sources and requires minimum capital investment. In contrast, renewable energy sources not only have poorer reliability (especially during the winter peak months) but they also provide a far more expensive means of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. For example, replacing half of the hard coal-fired plants in the EU27 with gas-fired combined cycle gas turbines would save 190 million tonnes of CO2. The costs for achieving this same amount of CO2 savings would be significantly higher – up to €250 billion more – if the EU were to rely on technologies such as nuclear and renewables generation. 8 Natural gas provides significant cost savings and emissions-reduction benefits in several other major sectors in addition to power generation. In the transport sector, which is today almost entirely fueled by petroleum , natural gas and LNG are already commercially-proven technologies. Natural gas is an established road transport fuel in many parts of Europe, with 1.6 million vehicles currently in operation, and LNG is fast becoming a major fuel in marine transport as well. Det Norske Veritas, one of the world's leading ship-classification societies, predicts that the majority of European ship owners will order ships that can operate on LNG by 2020. If this happens, the environmental benefits could be dramatic: an LNG-powered tanker uses 25% less energy and emits one-third less carbon dioxide (“CO2“) than a conventionally-fuelled vessel, while virtually eliminating other air pollutants from the exhaust stream. The decoupling of oil and gas prices further tips the scales in favor of natural gas as a transport fuel, as gas increasingly becomes a more economical (and less volatile) fuel substitute for oil. This advantage is expected to remain for the long term, as few expect crude oil prices to decrease to a level at which natural gas would become uncompetitive. In fact, one study shows that a gasfocused scenario in the transport sector could save the EU up to €73 billion by 2050 relative to the EU Roadmap baseline projections. I would like to be clear that the problem is not the goal of carbon emissions reduction or improving environmental quality. We can all agree that these are not only noble ideals, but targets that must be met. The EU strongly supports renewable technologies, and we do as well. But can anyone say that the appropriate level of care and diligence has been expended in 1) validating the technologies; 2) understanding the development risk associated with such a portfolio change; and 3) ensuring that the necessary government financial support and private capital is available? In my opinion, the answer is no. The problem is the premature, massive deployment of renewable technologies that simply cannot replace fossil fuel and nuclear power in providing firm baseload power, nor offer a substitute for conventional oil resources as a transport fuel. The promise of renewable power and biofuels remains and must be pursued. But the reality of these substitutes today is that they simply cannot perform the tasks required of them at anywhere near the cost or reliability of natural gas. Natural gas can do all that and more with current technology, without precluding the introduction of renewable technologies when they prove commercially viable in the marketplace. And, yet, the entire natural gas industry has been unfairly bundled with dirtier fuels and demonized for its carbon content in an effort by politicians and environmental alarmists to take all fossil fuels off the table as a means of addressing the climate challenges Europeans now face. Rather than this short-sighted view, European energy policy should be transparent and rational. It should be reflective of all relevant market, economic, technological and political drivers, and it should be implemented in close coordination with all relevant stakeholders, both domestic and foreign. A prosperous and secure Europe is a worthy goal, but it will not be achieved by physical and economic isolation from global energy markets. There is now a very clear and present danger that European regulators will pursue an imbalanced energy agenda that ignores the role that the expanded use of natural gas can play in achieving the EU’s main energy objectives: energy security, economic development and environmental protection. The reason for this is the persistent and unwarranted role that geopolitics plays in the EU-Russia energy relationship, where entrenched interests continue to push their self-serving agendas – agendas that create faulty incentives in the marketplace and, consequently, will prove suboptimal for Europe in the long term. It is time to acknowledge that the Cold War is over, and that we need each other for both of us to prosper. The ongoing recession in Europe has only worsened this situation, as the debt crises facing many EU member states continue to polarize and often paralyze the search for effective solutions and acceptable compromise. Unfortunately, the natural gas industry is not the only potential loser in this battle; the real loser is the European consumer, who will not be able to benefit from the cleaner emissions, cheaper price and greater reliability of natural gas. 9 Russia needs Europe to succeed in its efforts to reduce pollution and restructure its energy markets. Our fundamental energy interests are complementary, a function not only of human history but of the realities of geology and geography. Given the very dynamic and evolving nature of global energy markets today, there has never been a more crucial time than now for binding Russia and the EU into a closer relationship, one that values areas of mutual concern while, at the same time, ensuring that the policies of opening and integrating energy markets, protecting the environment and ensuring cost-effectiveness and supply reliability are maintained. The people assembled here in this hall today have the means to greatly increase the probability that Europe and other major energy markets pursue a rational and enlightened course of environmental improvement and economic benefit by promoting the expanded use of natural gas. Gazprom intends to continue this course of action, promoting rational energy policies in Europe and elsewhere and continuing to invest in new production and delivery capacity in order to lead the transition to a natural gas-driven world. A world in which a growing portion of transportation fuel is derived from natural gas, and dirty coal-fired power generation is supplanted by cleaner gas-fired power generation, complemented by a growing share of renewable energy generation. This promises to be a more secure, less volatile world, and a cleaner and less costly one too. It is vital that all of us avoid the temptation to let the policy debate take its own course, independent of our input. I would ask each of you today who recognize the merits of my case to reinforce and amplify this message in your own dealings with policy makers and opinion leaders at home and abroad. Let’s make sure that those in positions of political power and those in the media, each of whom may not be familiar with the facts, do indeed hear them and understand their implications. The sooner the practical implications of superficially attractive objectives are better understood, the sooner we can get ourselves on a path that, I sincerely believe, will benefit the citizens of Europe, Russia and the rest of the world. Thank you for your attention! 10