1 Format Guidelines for Papers Using Chicago

1

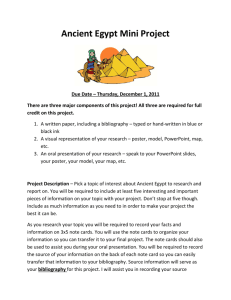

Specific Requirements :

Format Guidelines for Papers

Using Chicago-Turabian Bibliography Style

Chicago-Turabian style of formatting includes a title page, the main text, plus footnotes or endnotes, figures/illustrations, and a bibliography. All documents must be typed using twelvepoint Times New Roman font, with one inch margins on the top, bottom, left, and right.

Order of Parts of the Paper :

Title Page

Epigraph (optional)

Text

Figures/Illustrations

Endnotes (if used)

Bibliography

Title Page :

Your paper should begin with a title page. This page should be centered and in all capital letters. This page is NOT numbered. Place the title of the paper one-third of the way down, centered and in capital letters. Approximately three-quarters of the way down, type your name, the course title with number and section, and the submission date.

Sample title page:

THE INFLUENCE OF RUDOLF STEINER ON JOSEPH

BEUYS:

BEES IN AN ANTHROPOSOPHICAL APPROACH TO ART

Your Name

Art Appreciation 1100/003

December 4, 2010

2

Epigraph (Optional):

You may include an epigraph following the title page. The inclusion of an epigraph is completely optional and not a requirement. An epigraph is a quotation that establishes a theme for the paper. It should only be used if the words uniquely capture the essence of your work. The epigraph is on a separate page before the text. Do NOT put a page number on either the title page or the epigraph. An epigraph has a page number only if there is additional material in the front matter (this class paper should have no such additional material). Sources for epigraphs need not be cited in a note, but do need to be included in the bibliography.

Place the epigraph a third of the way down on the page and treat it like a block quotation; meaning that it is indented five spaces from the left margin . Do not enclose it in quotation marks. On the line after the epigraph give the author’s name, the title of the work (if literary), and (if appropriate) the date of the quotation, preceded by two hyphens or an em dash.

Examples:

What I dream is an art of balance, full of purity and serenity… something like a good armchair.

—Henri Matisse

Some people think the women are the cause of modernism, whatever that is.

— New York Sun , February 13, 1917

Sample epigraph:

What I dream is an art of balance, full of purity and serenity… something like a good armchair.

—Henri Matisse

Text :

The text of the paper includes everything between the front and back matter. It begins with the introduction and ends with the conclusion. Front matter is not considered in the pagination of text (see Pagination below). Text should be double-spaced, with the first line of a paragraph indented five spaces (usually one tab). There are no additional blank lines between paragraphs. Words written in a foreign language should be italicized as well as the titles of specific works of art or books. If you are referring to a work of art you should also refer to the image in the back matter by placing the corresponding figure number next to the title in parentheses.

Example:

Michelangelo’s David (fig. 1) was the inspiration for this body of work.

Pagination (Numbering) :

The first page of text starts with the arabic numeral one (1). The rest of the text and back matter (figures, endnotes and bibliography) are numbered consecutively using Arabic numerals.

Page numbers should be placed at the upper right hand corner of the page, flush right in the header (as on this document). It is not recommended that other identifying information—such as the student’s last name, date, etc.—be included in pagination.

Citation :

Citation is required to signal that you have used a source. This should be done at the end of the quoted or paraphrased sentence or if you are using ideas not your own within that sentence. Citation is done by placing a superscript number placed at the end of the sentence and corresponding to a footnote or endnote.

Examples:

Quote:

“The pope left one thousand scudi in the bank of Messer Antonmaria da Lignano to complete the statue.” 1

Paraphrase:

According to Vasari, Pope Julius II paid Michelangelo one thousand scudi to complete the statue.

2

1 Georgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists , trans. Julia Conaway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella. (Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 1991), 438.

2

Ibid.

3

4

Citing an idea not your own:

Vasari implied that Bramante and Raphael persuaded the pope to take

Michelangelo away from sculpture.

3

-OR-

Bramante and Raphael might have persuaded the pope to take Michelangelo away from sculpture.

4

-NOT-

Bramante and Raphael might have persuaded the pope to take Michelangelo away from sculpture. (This is plagiarism. You did not cite that it was Vasari’s idea).

Block Quotations :

Block quotations are used when a direct quotation is longer than three lines of text. It is single-spaced with one blank line before and after. Don’t use quotation marks but preserve those that are in the original text. Indent the entire quotation five spaces from the left margin and cite the quotation in a footnote or endnote.

Sample text page with a block quotation and footnotes:

1

Even this argument is not without its complexities since the eye, particularly the left eye, was sometimes given special treatment due to its association with myths regarding the falcon god Horus.

Egyptian belief held that Horus struggled with his uncle Seth to avenge the murder of Osiris. During this struggle, Horus lost his left eye which was restored, by the goddess Hathor (Fig. 14), as the wedjat eye.

1

Seth found him [Horus]—removed his two eyes from their sockets, and buried them on the mountain so as to illuminate the earth. His two eyeballs became two bulbs / which grew into lotuses . . . . Then Hathor, Mistress of the Southern Sycamore, set out, and she found Horus lying weeping in the desert. She captured a gazelle and milked it. She said to Horus, “Open your eyes that I may put this milk in.” So he opened his eyes and she put the milk in, putting (some) in the right eye and putting

(some) in the left one. She told him, “Open your eyes!” He opened his eyes, and she looked at them; she found that they were healed.

2

The wedjat eye was a potent symbol of wholeness and well-being, and hence a popular motif in ancient Egyptian art. “The pharaoh was the living manifestation or image of the falcon god Horus

(perhaps from the beginning of the dynastic era).” 3 This close association between Horus and kingship influenced the official image of the king, so much so that the king took on attributes of Horus and vice versa. Because of Horus’ celestial nature, the sun and moon were interpreted as his eyes.

4 Like Horus, the celestial sun god Amun-Ra was associated with myths in regard to the eye. The Eye of Ra, in ancient

Egyptian religion, is a separate deity which combined peaceful and vengeful aspects. These polarities were reconciled in the king and therefore the eye was important to convey his kinship with the deities. In turn, the king’s image influenced other figural art which might have inherited eyes possessing divine qualities.

_________________________

2

Toby Wilkinson, Dictionary of Ancient Egypt , (London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd., 2005), 108 and 259.

William Kelly Simpson, ed., The Literature of Ancient Egypt , London: Yale University Press, 2003, 98-99. From the Contendings of Horus and Seth , preserved on a papyrus dated to the reign of Ramses V. Translated by Edward F. Wente, Jr. This story has sections which are alluded to in Old Kingdom and Middle Kingdom texts, suggesting that the myth was longstanding.

4

Richard H. Wilkinson,

Toby Wilkinson., 108.

The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt , (London: Thames and Hudson, 2003), 54.

3 Ibid., 438-439.

4

Ibid.

5

Footnotes vs. Endnotes :

You must use either footnotes or endnotes. Footnotes are placed at the bottom of the page, where endnotes are placed in the back matter of the paper. Either footnotes or endnotes provide bibliographic information for a source cited. They can also be a place to add additional comments that are not appropriate for the text. It is recommended that you choose one or the other for purposes of clarity. In other words, don’t use both footnotes and endnotes for this paper.

Footnotes :

Footnotes appear on the same page as the text to which they refer. There should be a short rule between the last line of text and the first footnote on each page (a word processor should do this automatically). A number precedes each entry which corresponds to the text it references, and the font size is typically two points smaller than the body of the text. See the previous sample page.

Endnotes :

Endnotes should be listed together on a separate page after the illustrations and before the bibliography. Endnotes are part of the back matter so they are numbered consecutively with the text and illustrations that precede them. Label the list Notes in capitol letters centered on the page. Start each note with a blank line between entries and with the corresponding citation number in the text. See section below for a sample endnotes page.

Shortening Footnotes/Endnotes :

The first time a source is cited, it must include all the bibliographic information. The second time it is cited you may abbreviate the note. This is done if there is a break in entries. For successive entries use Ibid .

Example:

1 Toby Wilkinson, Dictionary of Ancient Egypt , (London: Thames and Hudson,

2

Ltd., 2005), 108 and 259.

Donald B. Redford, ed., The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Vol. 1

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 109

3 Toby Wilkinson. Dictionary of Ancient Egypt , 115.

4 Ibid.

3 Ibid., 111.

Ibid.:

Ibid . is short for the Latin term: Ibidem or “in the same place.” It can be used in footnotes or endnotes in place of repeating all the bibliographic information for a citation. It may only be used if it refers to the data that appears in the immediately previous note.

Examples:

1 Toby Wilkinson, Dictionary of Ancient Egypt , (London: Thames and Hudson,

Ltd., 2005), 108 and 259.

6

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid., 111.

Figures/Illustrations :

Your paper should include illustrations which are part of the back matter. This is the first element of the back matter. It comes immediately after the text and before the endnotes (if used) or bibliography. Label the first page Illustrations , centered at the top and in capitol letters. If you use more than one page, do not repeat the title. Do not use more than two figures per page, and make sure that each is accompanied by the appropriate caption (see Captions below). Be sure to use high resolution images.

Captions :

Captions for illustrations should be numbered consecutively according to how they are referred to in the text (fig. 1, fig. 2, etc.). After the number give the artist’s name, the title, the year completed, medium, dimensions, and who owns the work.

Example:

Fig. 1. Michelangelo, David , 1501, marble, height approximately 14’, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence.

If you copied the figure from a published source, you must identify that source in the caption.

Give the publication information in place of who owns the work.

Examples:

Book:

Fig. 1. Michelangelo, David, 1501, marble, height approximately 14’, in Jane Doe,

History of Michelangelo (New York: Sample Publishing, 1987). 242.

Website:

Fig. 1. Michelangelo, David, 1501, marble, height approximately 14’, Sample Art website, http://samplewebsite.org/mangelo/dav/id000123.htm (accessed June 22, 2010).

Sample illustrations page:

ILLUSTRATIONS

6

Fig. 1.

Michelangelo, David (detail), 1501, marble, height approximately 14’, in Jane Doe, History of Michelangelo

(New York: Sample Publishing, 1987). 242.

Fig. 2.

Michelangelo, David , 1501, marble, height approximately 14’, Sample Art website, http://samplewebsite.org/mangelo/dav/id000123.htm (accessed June 22, 2010).

Endnotes (see Endnotes under Text Citation):

Sample endnotes page:

7

NOTES

1. Clare Ford-Wille, “ Sfumato ,” The Oxford Companion to Western Art

(Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, 2008) [Accessed 04 February

2008], http://www.groveart.com/.

2. Ibid.

3. The infraorbital margin is the inferior half of the orbital rim or the lower border of the orbital opening, formed by the maxilla medially and the zygomatic bone laterally.

4. Pierre Gilbert, “De la mystique amarnienne au sfumato praxitélien,”

Chronique d’Égypte 33 (1958): 18-23. Unpublished translation by Aimée

Serefin, Savannah, Georgia, (2008). Page numbers in this and future notes refer to the published article.

5. Ibid., 19.

6. Romano, 108.

7. Gilbert, unpublished trans. Serefin., 22-23.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid., 20.

10. Rolf Krauss, “ Bek ,” The Oxford Companion to Western Art (Grove

Art Online, Oxford University Press, 2008) [Accessed 02 May 2008], http://www.groveart.com/.

11. Donald B. Redford, ed., The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt,

Vol. 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 109.

12. John Baines, “Ancient Egyptian Concepts and Uses of the Past: 3 rd to 2 nd Millennium Evidence,” Who Needs the Past? Indigenous Values and

Archaeology , R. Layton, ed., (London, 1989), 137, quoted in Redford, 109.

7

8

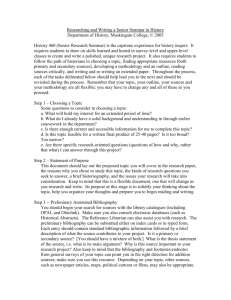

Bibliography :

A bibliography is used to let the reader know what sources you used to write the paper.

The paper must have a bibliography, and these should be properly cited in the text as well. Avoid websites whenever possible. Label the page at the center top bibliography in all capital letters.

The bibliography is part of the back matter and should be numbered consecutively with the text, illustrations, and endnotes. Entries should be alphabetized by the last name of the author. They are single spaced with a blank line in between. Also, use hanging indents. See the sample bibliography page below.

The paper must have a bibliography if it contains:

1. Sources cited in footnotes or endnotes

2. An epigraph (ie. Give the source of the epigraph).

3. Illustrations taken from books, websites, etc.

Sources to list in the bibliography:

1. Any texts you researched to write your paper.

2. Any texts cited in a footnote or endnote.

3. Any source from which you copied an illustration (including websites).

Below are examples on how to format different types of sources in either the note (N) or the bibliography (B). If the type of source you’re looking for is not on this list, please consult the recommended texts listed at the end of this handout.

Book with one author:

N:

1. Cyril Aldred, Akhenaten and Nefertiti , (New York: The Brooklyn Museum in

Association with The Viking Press, 1973), 176.

B:

Aldred, Cyril. Akhenaten and Nefertiti . New York: The Brooklyn Museum in

Association with The Viking Press, 1973.

Book with two authors:

N:

2. Alessandro Bongioanni and Maria Sole Croce, The Treasures of Ancient Egypt:

The Collection of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo , (Vercelli: VMB Publishers,

2003), 504-5.

B:

Bongioanni, Allessandro and Maria Sole Croce, eds. The Treasures of Ancient

Egypt: The Collection of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo . Vercelli, Italy:

VMB Publishers, 2003.

Book with an editor or translator in addition to an author:

N:

3. Heinrich Shäfer, Principles of Egyptian Art , 1919 , trans. John Baines (Oxford:

Griffith Institute, 1986), 291-2.

B:

Shäfer, Heinrich . Principles of Egyptian Art , 1919 . Translated by John Baines.

Oxford: Griffith Institute, 1986.

Editor or translator in place of an author:

N:

4. David P. Silverman, ed., Ancient Egypt, (Oxford: Oxford University Press,

1997), 88.

B:

Silverman, David P., ed. Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Online and other electronic books:

N:

5. Clare Ford-Wille, “ Sfumato ,” The Oxford Companion to Western Art (Grove

Art Online, Oxford University Press, 2008) http://www.groveart.com [accessed

February 4, 2008].

B:

Ford-Wille, Clare. “ Sfumato.

” The Oxford Companion to Western Art . Grove Art

Online: Oxford University Press, 2008. http://www.groveart.com

[accessed February, 4 2008].

Articles published online:

N:

6. Amarna Project, “Central City: The Great Palace,” http://www.amarnaproject.com/pages/amarna_the_place/central_city/index.shtml

[accessed 06 May 2008].

B:

Amarna Project. “Central City: The Great Palace.” http://www.amarnaproject.com/pages/amarna_the_place/central_city/inde x.shtml [accessed May 6, 2008].

9

Journal articles by author’s name:

N:

7. James F. Romano, “A Relief of King Ahmose and Early Eighteenth Dynasty

Archaism,” Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar 5 (1983): 108.

B:

Romano, James F. “A Relief of King Ahmose and Early Eighteenth Dynasty

Archaism.” Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar 5 (1983): 103-115.

Sample bibliography:

8

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aldred, Cyril. Akhenaten and Nefertiti . New York: The Brooklyn Museum in Association with The Viking Press, 1973.

Amarna Project. “Central City: The Great Palace.” http://www.amarnaproject.com/pages/amarna_the_place/central_city/index.shtml

[accessed May 6, 2008].

Baines, John. Visual and Written Culture in Ancient Egypt . Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 2007.

------. “Ancient Egyptian Concepts and Uses of the Past: 3 rd to 2 nd Millennium Evidence.” Who

Needs the Past? Indigenous Values and Archaeology. London, 1989. Quoted in

Donald B. Redford, ed., The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Vol. I .

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

------, and Jaromir Málek. Atlas of Ancient Egypt . Oxford: Equinox, Ltd., 1980.

Bongioanni, Allessandro and Maria Sole Croce, eds. The Treasures of Ancient Egypt: The

Collection of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo . Vercelli, Italy: VMB Publishers,

2003.

Bothmer, Bernard Von. Egyptian Art: Selected writings of Bernard V. Bothmer . Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2004.

Ford-Wille, Clare. “ Sfumato.

” The Oxford Companion to Western Art . Grove Art Online:

Oxford University Press, 2008. [Accessed 04 February 2008], http://www.groveart.com/.

Gahlin, Lucia. Egyptian Religion: The Beliefs of Ancient Egypt Explored and Explained .

London: Southwater, 2002.

10

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Turabian, Kate L. A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations. 7 th ed.

Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2007.

Barnet, Sylvan. A Short Guide to Writing About Art . 9 th ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey:

Pearson/Prentice-Hall, 2008.

The University of Chicago Press, The Chicago Manual of Style . 16 th of Chicago Press. 2010.

ed. Chicago: The University