Mountain Pine Beetle Influence on Lodgepole Pine Stand Structure

advertisement

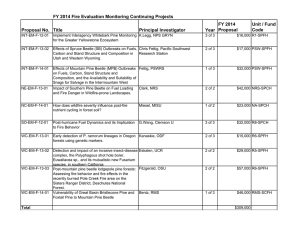

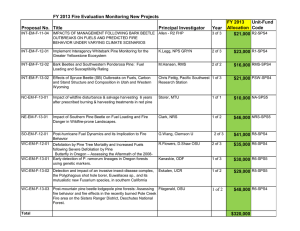

Gene D. Amman Bruce H. Baker MOUNTAINPINE BEETLE INFLUENCE ON LODGEPOLE PINE STANDSTRUCTURE ABSTRACT--EfJorts to control populations o[ mountain pine beetle (DendroctonusponderosaeHopk.) in lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta Dougl.) were evaluated /rom tree diameter distributions within treated and untreated stands. Beetle populations, where in[estation period was complete, declined in approximately the same number o[ years, and lodgepole pine survival in the two types o[ stands was comparable. However, suppressionmeasuresdid slow the rate o[ tree mortality in two stands still under attack. Mixed standso[ up to 36 percent trees o[ other specieswere proportionally as susceptible to beetle in[estation as those having lessthan 10 percent trees o[ other species.Survival increased with elevation, apparently because o[ adverse efJect o[ temperature on beetles. THE AUTHORS are, respectively,research entomologist,Intmtn. Forest and Range Exp. Sta., and entomologist,Div. of Timber Management, Intmtn. Region, U.S. Forest Serv., Ogden, Utah. high rate of reinfestationin stands where control of beetle populationshad been conducted. If beetie control methods are to be evaluated, their effectsmust be analyzedfor an entire infestation,period? Assessmentmust be based on comparisonsof treated and untreated stands. Data must include: (1) ratesof tree mortality and (2) residualvolumes. During late summerand early fall of 1969, blocksof lodgepolepine were sampledwithin the Teton-Targhee area. The pu.•posewas to evaluatebeetie suppression attempts. Residualstand structuresin treated and un•' hemountain ,pine ,beetie (Dendroctonus ponderosae treated areas were analyzedand comparedand, ,when Hopk.), one of the most aggressive of the ,barkbeetles, possible, tree mortality rates were also considered.No k:.ffismost of the large, dominanttrees in a stand of attempt,wasmade to determine.whethercontrol efforts lodgepolepine (Pinus contorta Dougl.) before an inreducedor preventedthe spreadof infestation.Little is festation declines (Fig. 1). Moreover, .infestationsreknown of the flight habitsof the beetle;so .thequestion cur (as in westernWyoming and southeasternIdaho), remainsas to whether•populations ,buildup in one stand and as a result of each suchreoccurrence,la,rgesums are expendedon attemptsto controlthe insect. The mostrecentbeetleoutbreakin westernWyoming began in the late 1950's. Approximately 1.3 million trees on the Teton National National Forest and Grand Teton Park were treated or harvested for mountain pine beetie control .,between1957 and 19682 The effort,waseven greateron the TargheeNational Forest, Idaho; over 1.7 million lodgepolepine were chemically treated or harvestedfrom 1962 throughthe spring of 1969. Methods of evaluatingforestinsectinfestationshave been describedby Knight (11), and controlproced•tres have been reviewed,byBalch (2). However, the literature offersno satisfactorymeans of assessing the effects of bark beetle control. Earlier efforts to evaluate the effectivenessof control jobs usually were based on beetleinfestationratesfor shortperiods(a year or so) insteadof on standstructureduringan entire infestation period(4, 8, 12). Chemicals sprayed on infested trees kill beetles beneath the bark (7, 9, 14), .reducingthe beetle population. However, as Kinghorn (9) noted, the amountof damagedone to a standby survivingbeetles is unknown. Moreover, such treatmentsmay not halt the outbreak. Klein and McGregor (10) reported a •Ethylene dibromide in diesel oil (EDB) trunks. 204 sprayed on tree and then move to others, or whether conditions favor the buildup of populations in a number of stands simultaneously. The 10 areaschosenfor study are typical of beetleinfestedstandsthroughoutthe Teton National Forest and Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming, and the Targhee National Forest, Idaho. Areas in which the infestation had run its course were desked. However, only six met this criterion; the other four were still under attack. Standsof trees on the sampledblocksqualifiedas pure or mixed merchantablelodgepolepine, although loggingwas not alwaysthe managementgoal. Attempts had been made to suppressbeetiepopulationson six of the 10 study ,blocks'while four 'were left untreated. Descriptions of standcomposition, elevationand habitat ty:peon thesestudyblocksarepresented in Table 1. Methods One 4-square-mile,blockwas selectedfor sampling within each study area. The shape of ,theblock varied becauseof vegetationalirregularities.Fifty percent or more of the treeswere to be lodgepolepine, a criterion eThe infestation period for the mountain pine beetle in lodgepole pine generally lasts about eight years. The period begins when about one tree per.acre is infested, peaks when approximately32 trees,peracre are under attack, and is about to end when less than one tree per acre is infested. JOURNAL OF FORESTRY Table 1. Proportion of Trees 4 inches dbh and Larger on Blocks in the Teton-Targhee Area According to Elevation and Habitat Type Engel- Whitebark- Block Name Elevation Habitat Lodg. epole Douglas-Subalpine mann type• pine fir fir spruce limber pines Trees Aspen per acre percent No. lnfestationconcluded Treated Pilgrim Mt. 6,900-7,700 A/P 86.7 2.7 7.6 1.4 1.6 0.0 311.0 Hatchet 7,000-7,800 A/P 90.9 6.9 0.2 0.7 0.0 1.3 274.5 Upper SpreadCreek 7,600-8,400 A/V 91.2 0.0 3.5 5.3 0.0 0.0 272.0 PacificCreek 7,200-8,400 TogwoteePass 8,700-9,300 Horseshoe-Packsaddle 6,600-6,900 A/V A/V A/P 79.0 41.9 64.1 0.0 0.0 14.3 16.8 14.5 15.0 3.3 20.1 0.4 0.9 23.5 0.0 0.0 0.0 6.2 288.5 236.0 233.5 Untreated lnfestation continuing Treated SignalMt. Warm River Pineview 6,800-7,100 5,500-5,800 6,200 P/C P/C P/C 97.0 93.2 98.8 2.8 5.3 0.3 0.2 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.5 0.9 304.5 271.5 286.0 6,000-6,500 A/P 95.7 3.2 0.4 0.7 0.0 0.0 278.5 Untreated Pine Creek XHabitat type: A/P = Abies/Pachistima; A/V = Abies/Vaccinium; P/C = Pseudotsuga/Calamagrostis. Classifiedaccordingto Roe and Amman (1970). Fig. 1. Snags indicate that many dominant lodgepole pine trees have been killed by the mountain pine beetle. In spite of losses, a large proportion of lodgepole pine trees have survived. met on all ,blocksexceptone at high elevation.Twenty fixed, circular, 1/10-acre plots within each block were locatedin a grid patterndescribedby Cole and Amman (3). One-tenth-acreopeningswere avoided.The elevation of each ,plot was recordedand the habitat type deter. mined by means of vegetational associations definedby Roe (13). Measurements were recorded •or art trees that were 4 inches dbh or larger. Individual trees were fisted by speciesand as.beingdeador alive. Dead lodgepolepine trees were classifiedas having been k'filed by the mountainpine beetle or by somecauseother than the mountain pine beetle;i.e., other bark beetles (Ips and Pityogenes), tree competition,or undeterminedcauses. The basalarea of survivingtreesthat avere9 inches dbh or larger was used to measurethe beetle'seffect on the operabilityof a stand.The 9-inch ,basewas chosen because it is the smartest merchantable sawtimber size considered in the loggingof lodgepolepine and because trees that are 9 inches dbh, or more, are most com- monly killed by the mountain pine beetle. Results and Discussion From 62-90 percentof the lodgepolepinesthat had a 4-inch dbh or more and 32-92 percentof the merchantable basal area survived the mountain pine beetle infestation.Survivalof smallrather than large-diameter trees.wasproportionallygreaterin aU areas (Figs. 2 and 3). The six lodgepolepine standsin which infestation was completesustainedattack from four to nine years. The other four standswere sti31irdested,even though outbreaks had begun from four to 14 years earlier (Table 2 ). Percent survival and length of irdestfitionperiod in both treated and untreated .areas at •bout the same elevation •ere similar. Differencesbetween areas appear to be iar•gelyrelated to elevation.Control efforts had slowed the rate of infestation in the two areas still under attack, but evidencesuggeststhat the ilffestation will continue until percent survival in treated areas approximatesthat in untreated areas. Where beetle infestationhad run its course,percentsurvivalof lodgepole pine indicatedthat control effortsusuallydid not save trees. APRIL 1972 205 Survival of Lodgepole Pine The untreatedPacificCreek block had approximately the samepercentsurvivalby individualdiameterclass as the treated Pilgrim Mountain and Hatchet areas (Fig. 2). Percentsurvivalof trees4 inchesdbh or more ranged from 63-69 percent and that of merchantable trees (9 inches dbh or more) from 36-42 percent (Table 3). Upper SpreadCreek, TogwoteePassand HorseshoePacksaddle, the other three blocks in which infestation had ended, showed different survival curves (Fig. 2). In Upper SpreadCreek, percentsurvivalof all lodgepole pines(4 inchesdbh. or more) was 74 percentand the merchantable .basalarea, 61 percent.Somechemical controland extensiveloggingof trees.mostsusceptible to attack or already infestedmay have reducedthe potentialfor beetlepopulationbuildupand resultedin greater survival in residual leave strips. Elevational differences may be important,as well. Percent survival beetlepopulationincreasedand, in 1969, 24 treesper acre were infested.Survival of lodgepolestems4 inches dbh, and larger, has been reducedto 76 percent and survivalof the merchantablebasalarea to 46 percent-not unlike the Pilgrim Mountain, Hatchet and Pacific Creek blocks. The large, current beetle population indicatesthat additionalmortality can be expectedon SignalMountainand that pine survivaleventuallywill be comparableto that in other areas in which the infestationperiodhasended. The relativelyfavorablesurvivalof lodgepolepine in the Pine Creek, Pineview and Warm River blocks reflectsrecentinfestations(Fig. 3). Basal area survival figuresare alsofavorable.However,afterthreeyearsof Fig, 2. Lodgepolepine survivalcurvesfor studyareas in which the mountain pine beetle infestation had ended. I • Togwatee Pass; 2 = Upper Spread Creek; 3 = Pilgrim Mauntain; 4 = Pacific Creek; 5 = Hatchet; and 6 • Horseshoe-Packsaddle. of both stems and basal area was higheston the untreatedTogwotte Pass block. This increasedsurvivalis probablyattributableto elevationrelated climatic conditionsthat adverselyaffect the beetle. a 9c • ec The Horseshoe-Packsaddle area showsa slightlydifferent survivalpatternby diameterclass:the larger dbh trees were reduced proportionallymore than in any othersampledblock.Survivalfor trees4 inchesdbh and over was 68 percent,which comparesfavorably with areas mentioned above, but only 32 percent of the merchantable basal area survived. Horseshoe-Packsaddle had the lowest elevation of blocks in which the infestationperiodwas complete. The remainingblocks supportcurrent infestations. The SignalMountain block is of interestbecauseit is still under attack after 14 years. The infestationwas treatedduring 10 of theseyearsand the mortalityrate slowed. However, when treatment was stopped, the Research Work Unit 2201, unpublished data, U.S. Forest Serv., lntmtn. Forest and Range Exp. Sta., Ogden, Utah. Table ioc 2. Periads af Mauntaln Pine Beetle Infestatlon •. 7o .• eo 13. "' õo • 4o I0 Start I I I I I I I I I [ õ • • • 9 I0 II I• I• 14 I• I•+ (l•t•$) Fig. 3. Lodgepolepine survival curves far study areas where and Mountain. IOC Treatment End Length Start 9C End Length I InJbstation concluded Treated \ I D. RM. Years Block name •_•'• Untreated the mauntain pine beetle infestation was current. I = Pineview; 2 = Warm River; 3 • Pine Creek; and 4 = Signal Treatment Infestation Treated .•:50 ---- • Pilgrim Mt. 1960 1968 9 1961 1967 7 Hatchet 1960 1968 9 1962 1968 7 1961 1968 8 1965 1968 4 1961 1968 None None --- --- None -- -- ?c Upper Spread Creek Untreated Pacific Creek TogwoteePass 1965 1968• 8 4 HorseshoePacksaddle 1968 8 1961 \ f 40 ...I Treoted -•, InJ•stationcontinuing Signal Mt. Warm River Pineview Untreated Pine Creek 1956 Current 1965 1966 Current Current 1966 Current 14 1957 1966 10 5 1966 Current 4 4 1967 Current 3 4 None -- -- % ---- Un•reo•ed Treated IO 5 6 7 8 9 D.B.H. I0 II 12 13 14 15 16+ (Inches) • Subtle increase and decline in infestation was difficult to date. The main infestationperiod was 1965-68. 206 JOURNALOF FORESTRY Fig. 4. Harvesting of lodgepole pine in the Upper Spread Creek area reduced residual stand susceptibility and consequently cut lossesta the mountain pine beetle. infestation, the Pine Creek block has lower numbers of percent in the Warm River stand. These differences in that standwere discontinued four yearsago, and the beefie populationhas increasedsince. This buildup suggests that factorsbelievedto contributeto increases in populations still exist,e.g.,treeshavingthickphloem and largediameter(1, 3). After four yearsof beetleactivity,the low amountof tree mortality on the Pineview block indicatesthat the survivingtrees in the large diameter classesthan the Pineview and War.m River stands after three and four yearsof infestation, .respectivelyß Also,only 56 percent of the ,basalarea in the Pine Creek block was alive, compared to 92 percent i•nthe Pineview block and 77 probably indicate that the infestation rate on the control effort has slowed the rate of infestation. Pineviewand Warm River blockshasbeenslowedby controlattemptsß Ultimate survivalis yet to be deter- percentof the stemsare still alive. Moreover, most tree mortality was attributable to other insects (Ips or mined. Pityogenes) . Duration of Inf0stati0n In areaswheremountainpinebeetlepopulations had subsided, infestations lastedeightto nine years.Togwotee Pass,where infestationlasted only four years, was the singleexceptionß Pilgrim Mountain, Hatchet and Upper SpreadCreek standswere treated, but the other three, Pacific Creek, Horseshoe-Packsaddleand Togwotee Pass, were not--an indication that control attempts did not slow the rate of in.festationin these areas. Control attempts in the Signal Mountain and Pineviewstandsand in the Warm River block apparentlyhavereducedtherateof in.festation. SignalMountainhasbeenunderattackfor 14 yearsß Controlefforts APRIL 1972 Over 90 The effectivenessof a chemical control project in reducingmountainpine beetlepopulationsis related to at least seven operational •actors: (1) steepnessof terrain; (2) ease of access; (3) training of control personnel; (4) experienceof control personnel; (5) radius of treatment applicationaround the stand of protectedtrees; (6) acreageinfested;and (7) initiation of control efforts while infestation is small. Most of these factors ,were optimal within the Pineview area, whichmayaccountfor the apparentsuccess of control. The effects of control on the Warm River infestation rate are not as apparentas in the SignalMountain and Pineviewblocks.However, the rate of tree mortality is slightly less than that in the untreated Pine Creek block. 207 Cost-benefitratios become an important consideration when treatmentperiodsextend over a number of years. For example, on Signal Mountain in Grand Teton National Park, the preservationof aesthetic valueswould be of primary concern.However,in spite of 10 yearsof controlwork (1956-1966), the mountain pine beefiepopulationhas increasedagain and, more than likely, the infestationwill proceeduntil the proportionalsurvivalby diameterclassis similar to that observedin the Pilgrim Mountain, Pacific Creek and Hatchetsamples. Beetleactivityis almostcertainto continueuntil mosttreesof thick phloemare killed. It would appearthat attemptsto suppressbeetlepopulations in national parks or in other areaswhere timber productsare not involved,are of little or no valueand that the eventual survival of lodgepolepine will be about the same whether or not the stand is treated. However, tree cover will persistbecausemany of the smallerlodgepolepinessurviveand other tree species, such as su.balpine fir and Douglas-fir, become more abundantasthey succeedlodgepolepine (13). lodgepolepine 9 inchesdbh and largeris apparentin all sampledblocks where the beetle .populationhas declined (Fig. 5) and seemsto accountfor much of the differencenoted in lodgepolepine survival. Percent survivalof lodgepolepine rangedfrom 37 percentin the lowestblock (averageelevation,6,800 feet) to 74 percentin the highestblock (averageelevation,8,900 feet). A similarrelationship holdsfor basalarea,which rangedfrom 32 percentat the Iomestelevationto 71 percent at the highest. Elevation-relatedtemperature differencesand their effectson beetle biologyprobably are responsible. Current studiesat the Intermountain Forest and Range ExperimentStation at Ogden (see footnote2) indicatethat at higher elevationsthe beetle is out of its .rangefor optimaldevelopment.Its biological activitiesare poorly synchronizedwith seasonal weather changes;so a two-year life cycle and low brood-survivalirequentlyresult. The effect of mixed speciesstands(lodgepolepine was 42 percentof the stemsin the TogwoteePass block) was also considered.However, Flint (5) ob- thresholdand beforethe costof protectionexceedsthe value of protectedvolume.Protection,to be justified, mustbe for a predetermined period of time so that the servedno differencein lodgepolemortality in mixed speciesstands.In addition,Roe and Amman (13) pointed out that the beefie is the primary agent in lodgepolepine removaland so providesfor succession by other tree speciesin standsunaffectedby wildfires. They foundthe beetleactivein standswherelodgepole pinetotaledlessthan40 percentof the stems. The relationship betweenlodgepole pinesurvivaland volume at time of cuttingwill warrant treatment expen- elevation existedwhether or not blocks,weretreated, an ditures. As an example, if 50 ,percentsurvival of lodgepolevolume,or merchantable basalarea, is arbitrarily set as the level at whicha standcan no longerbe loggedprofitably,then sufficient,basalarea remainsin only two of the sampled,blockswhere the infestation has ended. Both of these blocks the treated Upper SpreadCreek and the untreatedTogwoteePass--are at high elevations.Surviving,basalarea.was reducedto less than 50 percentin the other four standswithin eight •.onine yearsafter the start of infestation. indicationthat the land managerprobablywould not have to considerimmediateharvestingof standsabove about 8,000 feet in elevation. These standswould be relativelysafe from severedamageby the mountain pinebeetle. Differences in lodgepole pine survivalassociated with In stands such as Pineview and Warm River where timber products are involved, a thorough economic analysismay be helpfulto the land manager.It should be emphasized that protectedtimber shouldbe utilized before the stand volume falls below Elevational a memhantable Differences The effect of elevationon proportionalsurvival of elevation are consistent with the observations of Gibson (6), who found greaterlodgepolesurvivalat the upper ends of his strips, and with the .work of Roe and Amman (13) in which threehabitat typesin lodgepole pineforestsweredefined,whichgenerallyare relatedto elevationbut varywith slopeandaspect.Risksof losing lodgepolepine to the mountainpine beetlein the three Table 3. LodgepolePine BasalArea (sq. ft./acre) Living and Dead on 10 Blocksin the Teton-TargheeArea for Trees 9 inches dbh and Larger Basal area Killed by mountain Blockname Surviving pinebeetle Killed by othercauses sq.ft. percent sq.ft. In, stationconcluded percent Total sq.ft. percent sq.ft. PilgrimMt. 28 38.1 43 39 62.4 58.7 2 3.2 73 UpperSpreadCreek 54 60.7 29 33.3 5 6.0 88 PacificCreek 43 42.4 57 56.7 1 0.9 101 Togwotee Pass 53 71.3 31.9 18 24.5 3 29 66.8 1 lnfestationcontinuing 4.2 26 45.6 30 14 3 22.0 5.4 54.0 <1 0.4 0.7 2.2 64 49 30 56.0 23 42.4 1 1.6 54 Treated Hatchet 22 36.1 1 1.5 62 Untreated Horseshoe-Packsaddle 14 1.3 74 44 Treated SignalMt. Warm River Pineview 49 45 77.3 92.4 I 1 56 Untreated Pine Creek 208 JOURNALOF FORESTRY and pure standsto mountainpine beetle attacks.However, once a beetle irffestationis concluded, mixed 8O o=Trees • 70 A/ standswill havea highertotalresidualstockingdue to x=Bosol Areo •//- •1 o // the presenceof otherspecies. Conclusions As a resultof thisstudy,the authorsrecommend: ß That managementgoalsbe well definedahead of beetlecontroldecisionsand that land usesbe thoroughly evaluated.When harvest opportunitiesare threatened, chemicalcontrolsthat might slow the rate of infestationmay or may not withstand economicand environmental scrutiny.Where recreationalor aesthetic considerations are the only threatened•esourcevalues, 6o o o, 50 •••• %x•/•/•--Bosol Areo chemical 40 x / ,"• I 6,500 • 7,000 I 7,500 I I 8,000 I I 8,500 s I 9,000 Elevotion (Feet) Fig. 5. Survival of lodgepole pine 9 inches dbh, and larger, from mountain pine beetle attack increased directly with elevation. I = Togwotee Pass (untreated); 2 = Upper Spread Creek (treated); 3 ---- Pacific Creek (untreated); 4 = Pilgrim Mountain (treated); 5 ---- Hatchet (treated); and 6 ---- Horseshoe-Packsaddle (untreated). habitat typeswere lowestin the Abies lasiocarpa/Vacciniumscopariumassociation(high elevations),highest in the A bies lasiocarpa/Pachistimamyrsinitesassociation (mid-elevations), and intermediatein the Pseudotsuga rnenziesii/Calarnagrostis rubescens association (low elevations). Our data follow the same trend for the Abies/Vaccinium and Abies/Pachistima associations. However, we did not have data from a block in the Pseudotsuga/Calamagrostis association,where the infestationperiod had already ended. Basingrisk on habitat type rather than elevationalonewould permit consideration of differencesin slope,aspectand latitude. differencein susceptibility of lodgepolepine in mixed APRIL 1972 Tree cover harvest easier to fulfill. Literature Cited 1. AI•I•AN, GENE D. 1969. Mountain pine beetle emergence in relation to depth of lodgepole pine bark. USDA Forest Serv. Res. Note INT-96, 8 p. 2. BALCH, R. E. 1958. Control of forest insects. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 3:449-4•8. 3. COLE, .WAL?EEE., and GENE D. AI•II•AN. 1969. Mountain pine beetle infestations in relation to lodgepole pine diameterS. USDA Forest S6rv. Res. Note INT-95, 7 p. 4. Flint (5) and Roe and Amman (13) also found no is not reconunended. festation, and would make the recommendation of immediate Mixed Species Mixed speciescompositionhas been considereda meansof reducingtimber lossesto many insects(2). However,our data on the mountainpine beetledo not supportthis supposition.Percentsurvival of lodgepole pine was no greaterin the Horseshoe-Packsaddle block that contained36 percentotherspeciesthan in blocks that had lessthan 10 percentotherspecies.About 68 percentof the lodgepole,pine stemssurvivedon the Horseshoe-Packsaddle block,but only32 percentof the merchantable .basalarealived.AlthoughTogwoteePass containedthe highestproportionof other tree species (58 percent),the increasedsurvivalof lodgepolepine was attributedto the effectof climateon the biologyof the mountain pine beetle. The proportion of other specieswould have to be considerablymore than 36 percentin the alerational zone of optimal beetle developmentfor lodgepolepinein mixedspecies ,foreststo be less susceptibleto mountainpine beetle damage. treatment will persistbecauseof lodgepolepine survival in the smallerclassesand succession by other tree species. ß That a commerciallodgepolepine stand (having many trees of large diameter and thick phloem) be harvestedimmediatelyif a pine beetle in.festationis observed.High elevationstands(over 8,000 feet) are an exception.Harvesting removes the potential for beefie epidemicsand the.need for chemicaltreatment. If harvestingof an infestedstand of lodgepolepine is attempted,it should be timely to prevent tree losses from reachingthe point where the operationbecomes economicallyunsound. ß That creationof lodgepolepine blocksof different agesand separationof blocksof similar age, a management alternativesuggestedby Roe and Amman (13), would prevent large areas of ,pine from becoming susceptible simultaneously to mountainpine beetlein- CRAIGHEAD, F. C., J. M. MILLER, J. C. EVENDEN, and F. P. KEEN. 193/. Control work against bark beetles in western forests and an appraisal of its results. J. Forestry 29:100110/8. 5. FLINT, H. R. 1924. Various aspects of the insect problem in the lodgepole pine region. U.S. Forest Serv. D-1 Appl. Forestry Notes 54, 4 p. 6. GIBSON, A. L. 1943. Status and effect of a mountain pine beetle infestation on lodgepole pine stands. Miraco. Rep., USDA Bur. Entomol., Forest Insect Lab., Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, 34 p. 7. -1943. Penetrating sprays to control the mountran 8. pine beetle. $. Econ. Entomol. 36:396-398. JOHNSON, PHILIP C., and RICHARD F. SCHMITZ. 1965. Dendroctonus •onderosae Hopkins (Coleoptera: Scolytidae), a pest of western white and ponderosa pines in the Northern Rocky Mountains. A Problem Analysis, USDA Forest Serv., Intmtn. Forest and Range Exp. Sta., Ogden., Utah, 87 p. 9. KINGHORN, J. M. 1955. Chemical control of the mountain pine beetle and Douglas-fir beetle. J. Econ. Entomol. 48:501-504. 10. KLEIN, W. H., and M.D. McGREGOR.1966. Forest insect conditions in the Intermountain States during 1965. USDA Forest Serv., Region 4, Div. Timber Manage., Ogden, Utah, 13 p. 11. KNIGHT, FREI) B. 1967. Evaluation of forest insect infestations. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 12:207-228. 12. MILLER, J. M., and F. P. KEEN. 1960. Biology and the western pine beetle. USDA Forest Serv. Misc. 381 p. 13. RoE, ARTIIUR L., and GENE D. AMI•AN. 1970. The pine beetle in lodgepole pine forests. USDA Forest 14. Pap. INT-71, 23 p. WICKMAN, B. E., and R. L. LYON. 1•2. of the mountain pine beetle in lodgepole J. Forestry 60:395-399. control of Pub. 800, mountain Serv. Res. Experimental control pine with Lindano. 209