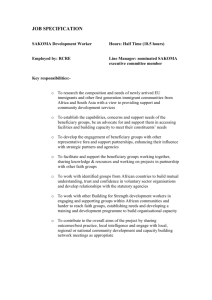

Delivering Training and Technical Assistance

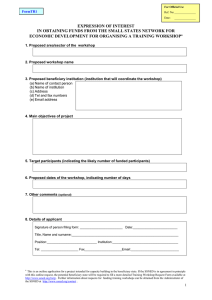

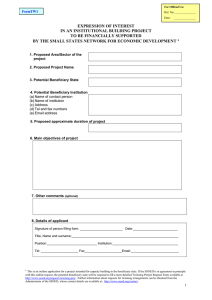

advertisement