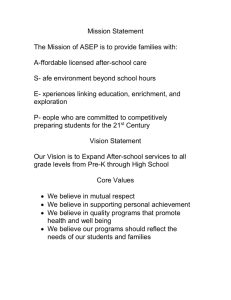

A Different Kind of Child Development Institution

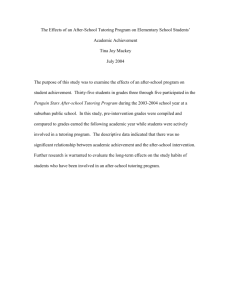

advertisement