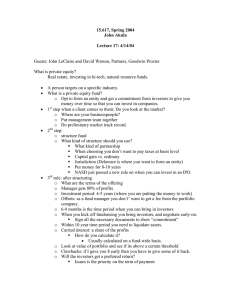

nothing ventured, nothing gained

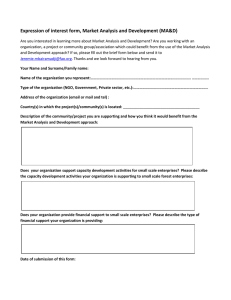

advertisement