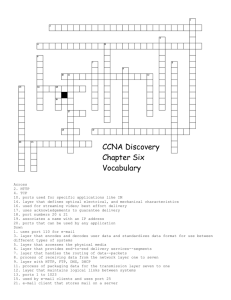

Chapter 1 - S3 amazonaws com

advertisement