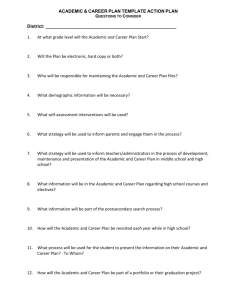

Primary School Assessment Guidelines for Teachers

advertisement