International Delegations and the Values of Federalism

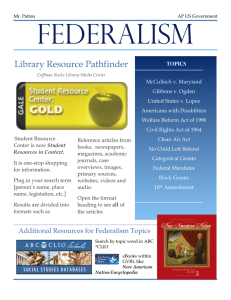

advertisement