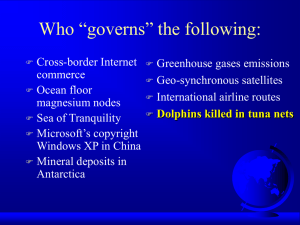

International Regimes for Human Rights

advertisement