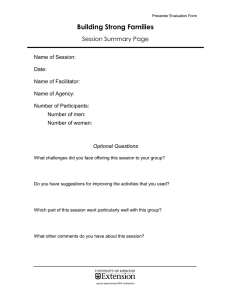

Workshop Administration

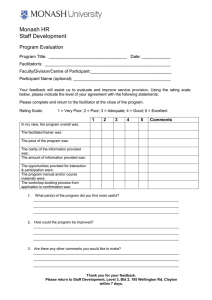

advertisement