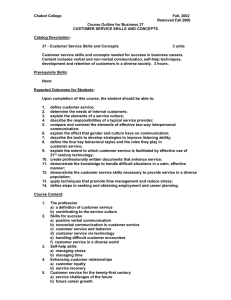

Good practice guidance on the use of self

advertisement