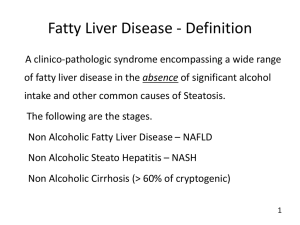

The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver

advertisement