Hartford Open Choice Students` School Engagement: The Role of

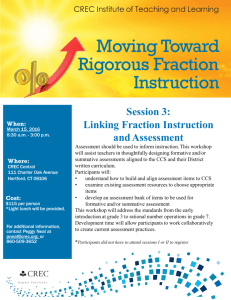

advertisement