2013 Annex C Review of Environmental Stewardship

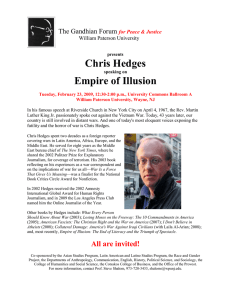

advertisement