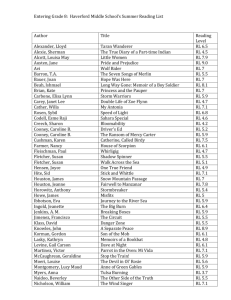

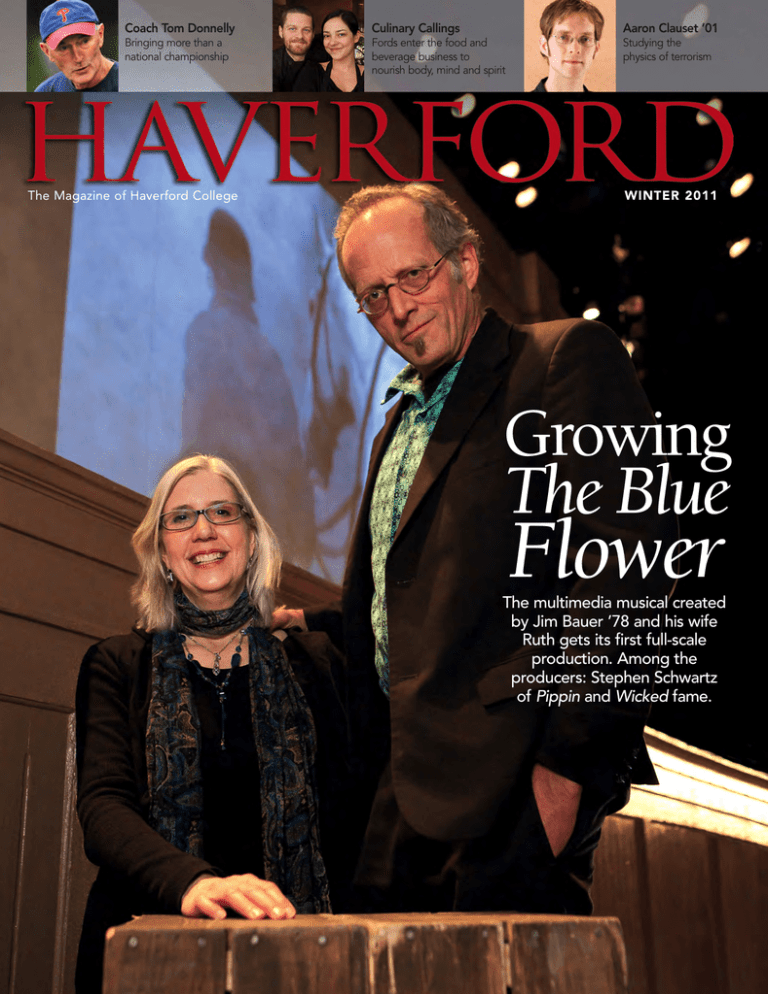

Winter 2011 - Haverford College

advertisement