Reliable or Fickle?

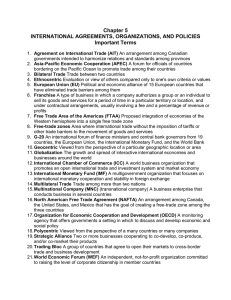

advertisement