BamBrogan v Hyperloop 14 July 2016

advertisement

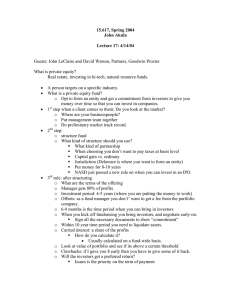

BamBrogan v Hyperloop 14 July 2016 1 BamBrogan v Hyperloop 14 July 2016 Brogan BamBrogan is pissed after Hyperloop One chief counsel Afshin Pishevar put a noose on his chair. By his own admission, he resigned after a series of actions he alleges top management made to disadvantage employees and investors. Not a boring stockholder suit BamBrogan’s complaint would have been another boring legal brief about Series A & B stock and stockholder dilution were it not for allegations of Russian investors capable of violence, a girlfriend making $40,000 a month, and nooses left on chairs. For most of us, this will be a voyeuristic look into a dysfunctional startup. This story promises to be the OJ story of the tech world. But what are the interests of the players? The management of Hyperloop One is most directly affected. They will have to defend the suit. A loss would unseat them and perhaps land them in jail. Employees of the company will spend hours at the water cooler discussing the case, accomplishing little while this story plays out. In the best scenario, they could end with more control and a shot at the pot of gold at the end of the tube. The State of California has an interest in enforcing its employment laws. The investors have an interest to see that their invested funds were managed to maximize the likelihood of a profitable outcome. Finally, this fight could be the end of the Hyperloop dream Investors Investors in Hyperloop One have every reason to expect that management has expended whatever portion of the $100 million they have contributed to the venture in a way that maximizes the likelihood of Hyperloop’s success and the economic benefit they derive. The suit makes serious allegations in several areas. It describes cash outlays for services at above market rates for results of questionable value. Whether these costs were material or of value is a matter for the jury to decide. The allegations of self-dealing are easier to prove. That the company chose to give its investment banking business for a fee to a company controlled by a board-member’s brother, when another firm offered to do it free in expectation of future business is perhaps bad judgement. An examination of Fideras.com, the investment banker’s website, shows a connection to another firm, Zanbato Inc, founded by Joe Lonsdale. The Fideras website, now only a splash page with a secure login, is, technically a subdomain of Zanbato. You can verify this by going to the Fideras login dialog and clicking Privacy Policy. • • The suit points out that Hyperloop One engaged the services of The Pramana Collective for public relations. Later, Pishevar started seeing Meredith Kendall of the Pramana Collective socially. BamBrogan asserts that more or less simultaneously, the monthly rate paid to Pramana was increased from $15,000 per month to $40,000. Further, BamBrogan asserts, the commercial relation with Pramana was terminated after his engagement to Kendall faltered. Kendall left Pramana in May 2015, according to her LinkedIn page. Don’t bother looking for Pramana’s website; there is none. 2 Pishevar and Kendall at the Build Gala 7 March 2015 In another allegation, BamBrogan asserts that management of the company interrupted engineers’ work to conduct tours of the facility. This is a matter of style, opinion, and priorities. If it is true that one guest was a “Los Angeles nightclub doorman” unrelated to fund raising, that would be over the top. The suit also asserts that company facilities were used for parties, interrupting engineering work. Investors Investors in a deal like Hyperloop go in with their eyes wide open. They expect most ventures to fall apart. They also expect to negotiate terms and voting privileges that typically favor the founders and earlier investors. In all cases, however, they expect their money to be used for the purpose of building a profitable company. They have a legal right to expect that management protects 3 their interest with the same or greater degree of care as their own. It’s called fiduciary duty. Investors are tolerant of small shenanigans; it’s a price of doing business. As long as the investment is showing promise, they tolerate management’s quirks. When things start falling apart, investors start taking a deeper interest and may install a new management to salvage the investment. In most cases, when the handwriting is on the wall; investors seek to close the company with the least additional loss. Hyperloop is not a typical faltering venture. The underlying technical concepts are proven. The Scarborough RT commuter rail in Toronto has used magnetic levitation and linear motors since 1985. The company has a competitor, Hyperloop Transportation Technologies (HTT), giving credence to the concept. SpaceX is constructing a Hyperloop test track in preparation for a competition of thirty academic teams building prototype capsules. Hyperloop One is demonstrably ahead of HTT. It is unlikely that investors would pull the plug now, having committed $100 million and being in first place in the technology race. Investors may, however, be displeased with management’s performance. The Russian contingent lead by Summa Group has already established its position in reaction to the lawsuit. It has cast its lot with management, calling the lawsuit an “internal matter.” Where other investors including GE Ventures and SNCF (the French national railway) take sides remains to be seen. The investors will watch carefully the court’s reaction to BamBrogan’s claim of breach of fiduciary responsibility (the seventh cause of action). They are likely situated similarly to the employees with stock options – money or time invested, but little voting power. Employees The employees of Hyperloop One fall into four categories: the four plaintiffs BamBrogan, Sauer, Pendergast, and Mulholland, seven additional who signed the letter to management, as many as fifty who cooperated with management, and the rest who are probably hoping to keep a job. 4 The majority of employees at Hyperloop One didn’t see the goings on with the public relations agency or the investment bank, both of which are in the Bay Area. They were unlikely to know much about the various classes of stock, which they would probably own only for a few hours when they exercised their stock options at some sunny day in the future. They are today concerned about their jobs which are in jeopardy. The lawsuit alleged that as many as fifty employees aided management by “engaging in unlawful conduct … that caused harm to Plaintiffs.” These folks are in a most tenuous position. They may be called upon to defend themselves in court. Whether the company pays their legal bill is unknown. If BamBrogan is eventually restored to power, they may not be well favored. The seven who signed the letter to management but did not sue seem to have made their peace with the company. Josh Giegel was promoted to chief technical officer, given a seat on the board of directors, and in a curious twist, named as a co-founder of the company. The four plaintiffs can’t be much worse off. In the worst case, that they lose, they will be out attorney’s fees. The first round of press analysis has branded the lawsuit crazy, insane, and delusional. BamBrogan will be hard pressed to find a job with Lonsdale’s description of him as “unstable,” and “gone haywire” following him. If they prevail, the four would be reinstated at Hyperloop One. How that would work if the current board and management stay in place is hard to say. To win the case, the four will have to prove breach, in which case they will probably be working for a new team. Then there’s the matter of money. The insurance company writing the directors’ insurance is likely to be unhappy. If fraud is proven, however, the D&O policy will likely exclude it. How much the four would ask for in general, special, and consequential damages will be part of the public saga. State of California The State of California has a lot invested in the outcome of this case. California is home to many startups. The state will want to see that investors and employees see justice in this very visible case, else other states might be a better home for 5 startups. Whether the fiduciary duty claim is more appropriately handled in Delaware Chancery Court, I cannot say. 1102.5. (a) An employer, or any person acting on behalf of the employer, shall not make, adopt, or enforce any rule, regulation, or policy preventing an employee from disclosing information to a government or law enforcement agency, to a person with authority over the employee, or to another employee who has authority to investigate, discover, or correct the violation or noncompliance, or from providing information to, or testifying before, any public body conducting an investigation, hearing, or inquiry, if the employee has reasonable cause to believe that the information discloses a violation of state or federal statute, or a violation of or noncompliance with a local, state, or federal rule or regulation, regardless of whether disclosing the information is part of the employee's job duties. (b) An employer, or any person acting on behalf of the employer, shall not retaliate against an employee for disclosing information, or because the employer believes that the employee disclosed or may disclose information, to a government or law enforcement agency, to a person with authority over the employee or another employee who has the authority to investigate, discover, or correct the violation or noncompliance, or for providing information to, or testifying before, any public body conducting an investigation, hearing, or inquiry, if the employee has reasonable cause to believe that the information discloses a violation of state or federal statute, or a violation of or noncompliance with a local, state, or federal rule or regulation, regardless of whether disclosing the information is part of the employee's job duties. In order for the retaliation and wrongful termination causes (first and second) to stick, the plaintiffs will need to prove the breach of fiduciary duty claim (seventh cause). 6 That’s going to be a high hurdle, and one that Orin Snyder will fight. He’s a feisty one. He will seek to drown Cotchett, Pitre & McCarthy, LLP in depositions and discredit its witnesses on the stand. BamBrogan claims that CEO Rob Lloyd already threatened to “bleed the employees dry with frivolous lawsuits.” Whether BamBrogan, Sauer, Pendergast, and Mulholland have the cash between then to pay the legal bills or whether Cotchett, Berger, and Buescher have the energy to pursue the case to conclusion on a contingency basis remains to be seen. Hyperloop One Management A loss in this case would be a severe blow to Shervin Pishevar. It would open him up to action from the company’s investors. That could separate him from Hyperloop One. He most certainly has other resources to fall back on. His ability to sponsor other startups would be crippled. The same goes for Joe Lonsdale. It is unclear what outcome is likely for Rob Lloyd. He had to be named in the suit; he is after all CEO of Hyperloop. It seems however that he and BamBrogan had at least a working relation during Lloyd’s early tenure (from June 2015). BamBrogan described Lloyd conceding Afshin Pishevar as “untouchable”, which indicates a certain level of trust between the two. Lloyd gave up a shot at CEO of Cisco. Whether he could land on his feet at another company is a matter for speculation. Hyperloop One and its top three executives will have to fight this one. They took the first step, hiring New York lawyer Erin Snyder. That portends a nasty fight. The Biggest Loser Perhaps the biggest loser in this fight will be the public, whose imagination has been captured by the dream of a new mode of transport that could move people from downtown LA to San Francisco in thirty-six minutes. 7