The Effects of Culturally Sensitive Education in Driving South Asian

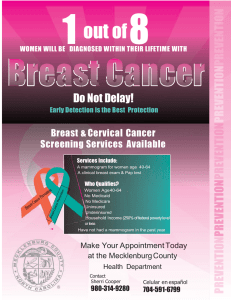

advertisement