National Strategy for Sustainable Development for the Slovak

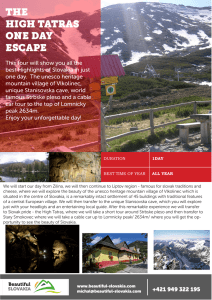

advertisement