Electrolytic Resistance in Evaluating Protective

advertisement

Electrolytic Resistance in Evaluating

Protective Merit of Coatings on Metals

R. CHARLES BACON, JOSEPH J. SMITH, AND FRANK M. RUGG

Bakelite Corporation, Bloomfield, N . J.

*

against the passage of corrosive material from the environment

to the corrodible metal surface.

Since this combination of barrier properties determines the

protective life of the coating, a thorough study of underwater

coatings for metals should be centered on the complete system

metal-coating-aqueous environment. I n this system the ionic

mobility within the coating was believed to be related to the ease

of passage of corrosive constituents through the coating to the

metal. As a result, the electrolytic resistance due t o the cbating

was thought t o be a measure of protection.

To test the validity of this idea experimentally, the coated

metal and aqueous environment were incorporated in an electrochemical cell aa follows:

In the examination of over 300 test systems the electrolytic resistance of organic coatings on immersed metals has

been found to be reliable for following protective behavior

and for predicting coating life, generally, in less than one

fifth the time required by the usual exposure tests based

on visual observation. These results are consistent with

the assumption that the protection offered by underwater

coatings is determined by the ease of passage of corrosive

materials or ions through the coating to the corrodible

metal surface, and that this diffusibility is in turn related

to the electrolytic resistance of the coating. In measuring

coating resistances the standard method for the determination of the internal resistance of batteries was employed, the voltage being measured by means of an electronic potentiometer. As only exceedingly small currents

are drawn and these only during the seconds of measurement, coating failure is not accelerated and significant

polarization is precluded.

metal/coating/aqueous environment/HgCl/Hg

The standard technique for determining the internal resistance

of a battery waa then employed. This method consists in

measuring the open circuit potential, EO,of this cell and then the

potential, E,, obtained when a n appropriate known resistance,

R,, is momentarily connected across the cell terminals. From

these values the internal resistance, R,, can be calculated from the

following equation:

A

NEED of long standing has been a satisfactory laboratory

test for predicting the corrosion protective merit of organic

coatings on submerged metals. In considering t h e development

of such a test, a study of the possible significance of various

measurable properties indicated the likelihood of a correlation

between the electrolytic resistance of the coating and corrosion

protection. To test the validity of this concept, a suitable apparatus was constructed and a series of experiments carried out

in which both coating resistance and extent of visible substrate

corrosion were followed. The purpose of this publication is to

show b y means of representative data the reliablity of electrolytic resistance values as a measure of coating protection and as a

means of predicting protective life.

Wirth (4) appears to be the only obher investigator to report

specifically on the electrolytic resistance of submerged protective coatings. He measured the galvanic currents which

flowed from steel to zinc and t o silver electrodes through films,

both attached to the steel and unattached to any substrate.

From these current values and the cell potentials obtained by

opening the circuit momentarily, the film resistances were calculated. The results were used as an aid in constructing a theory

on the mechanism of coating protection.

RI

=

R,

(2 -

I)

The resistance due to the presence of the coating can be determined by subtracting from resistance Ri the resistance obtained

using a similar cell in which the coating is absent. This latter

correction is often negligible, since the resistance due t o the

coating is usually of a much higher order of magnitude than that

due t o the remainder of the cell.

Only the small currents which flow while obtaining the closed

circuit potentials E, are passed through the test cell. Since the

time involved in obtaining this value is very short (less than

5 seconds) and the measurements are not made frequently, no

Bignificant cell polarization or galvanic breakdown of the coating

occurs.

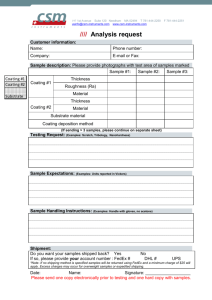

INSTRUMENT USED

A detailed wiring diagram of the instrument used in measuring

open and closed circuit potentials is shown in Figure 1. This

instrument, referred t o as the Protectometer, is divided functionally into three sections: the potentiometer, the cell and

switch circuit, and the null indicator. The null indicator registers

zero when the voltage supplied by the potentiometer is equal,

but opposite in sign, t o the voltage across the test cell. This

indicator is a slightly modified Leeds & Northrup thermionic

amplifier (No. 7673) together with a Leeds & Northrup enclosed

lamp and scale galvanometer (No. 2420~). Since the modification of the amplifier consists primarily in changing the values of

certain resistors, Figure 1 includes approximate values of all

resistances.

The utility of this amplifier depends largely upon its stability

and the low grid current (less than

ampere) of the Westinghouse RH 507 tube. This low grid current permits voltages to

be measured to the closest millivolt in systems having an internal

resistance up to 10,000 megohms. A detailed discussion of the

thermionic amplifier and the behavior of this tube has been

THEORETICAL BASIS

Metallic corrosion, whether an electrochemical or a direct

chemical process, is a surface attack on the metal resulting from

contact with certain constituents of its environment. It is

generally accepted that organic underwater coatings, such as

paints, retard corrosion primarily by reducing the amount of

corrosive material which gains access to the metal surface. Accordingly, a coating should be continuous and should remain,

throughout extended periods of immersion, reasonably impermeable, coherent, and adherent t o the metal. Furthermore, many

underwater primers contain inhibitive pigments which further

retard corrosion, presumably by interposing an impervious passivating film over the metal surface. The combination of these

properties in the coating, then, enables it t o serve as a barrier

161

162

INDUSTRIAL AND ENGINEERING CHEMISTRY

Vol. 40, No. 1

curve designated. “good” in Figure 2 is

typical of such variations.

The cause of the initial rise and subsequent variations in coating resistance

designated as “repairing tendency” is

not known with certainty. However,

since measurements of the resistance of

immersed detached resin films do not

as a general rule show this repairing

tendency, this behavior appears to be

due, a t least in part, to processes occuralv

ring a t the metal-coating interface. The

following mechanism appears to explain

this phenorrenon. The initial decrease

in resistance is due to the permeation

of water and the tiansport of conducting constituents within the coating. As

a result, corrosion product barriers form

Switch Circuit

a t the metal-coating interface and perFigure 1. Schematic Wiring Diagram for Protectonieter

haps in the pores and interstices new

this interface. These barriers-for exK~ (ohmli) = 10,000,Rz = 5 , & = 10-20 depending o n the floating grid bias for the particular

RH 5017 tube used, Ra = 10,000, Rs = 5000, Rs = 10,000, R7 = 15, RE = 20, Rs = 10,000, RID= 150,

ample, gases, oxides, passive filmR I I = 50. Rn = 3500.

El = t w o EverReady air cells, A2600; Ez = one EverReady air cell, A2600.

block the passage of conducting particles

Care must be taken to Pnsure adequate insulation in the selection of switches Sc, s2) Sa, Sd,

to the metal surface, and this leads to the

and S o .

increase in resistance. As the corrosion

proceeds at a retarded rate beyond this

presented by Cherry (1) and Hayes (3). I n order to determine

point, the pressure due to increased amounts of corrosion products

the cell resistance (E,) from Equation 1 it must be possible t o

produces localized ruptures in the film structure. These permit

a less hindered transport of conducting constituents and henre

connect a known resistance (Re)across the cell when desired.

This is accomplished by switches 8 2 , 8 3 , and 8,. The purpose

lead t o a decrease in resistance. The cycle may repeat itself many

of the auxiliary unit i,s to permit the connection of a low resistance

times before the complete breakdown of the film. In conformity

with this mechanism, microscopic examination of unpigmented

source of voltage (+1.5 t o -1.5 volt) in series with the test cell.

coatings having high resistancrs during immersion revealed

This arrangement allows good accuracy ( * 5%) in resistance

black spots under the coating which are presumably manifestadeterminations when the voltage supplied by the test cell is

tions of one type of corrosion-product bariier formation.

less than 0.1 volt. The resistance contributed by this potentiometric auxiliary unit is negligible in comparison to the resistances

normally determined.

EXPERIMENTAL PRQCEDLRE

BEHAVIOR OF COATING RESISTANCE

The resistance technique was developed as an aid in studying

snd evaluating coating compositions being considered for use

on the hulls of seagoing vessels. As a result, the experimental

work has been concentrated on the test system mild steel/coating/

sea water. In order t o avoid contamination of, and junction

potentials with, these test half-cells, a special reference electrode

Hg/HgCl/sea water, was used.

When coating resistance determinations were first undertaken

the values for 1 square centimeter of submerged surface were

f m n d t o be as liigh as 1OLl ohms shortly after the beginning of

the immersion, and as low as lo3ohms after a number of months

of exposure. As a result, it has been more convenient to represent

the data graphically in the form of logarithm of resistance us.

time instead of resistance us. time.

Figure 2 gives representative resistance behaviors for three

classes of coatings, those giving poor, fair, and good protection,

respectively. Most coatings, if continuous, have resistances in

the neighborhood of log R = 9 during the first 5 t o 10 minutes of

immersion, followed by a decrease in resistance which may

vary considerably in steepness and duration. The resistance

of poor coatings continues to decrease and leads to failure during

the first thirty to sixty days of immersion. Fair coatings may

level off or even rise slightly in resistance after the initial decrease.

However, a subsequent decided decrease in resistance heralds

coating failure in approximately six months of exposure. With

good coatings an initial decrease in resistance is followed by an

abrupt rise to approximately the original value. Thereafter

the log R value may remain substantially unchanged or increase

and decrease irregularly in the high resistance region. The

After having observed in preliminary experiments that coatings

which maintained higher electrolytic resistances during immerIO

r;

u

$

P

2

2

B

E

I2

P

6

9

8

7

g3

6

;

B

3

P

5

6

4

I/

s

3

0

30

60,

90

17.0

150

TIME IN DAYS

~i~~~~2.

schematic~~~i~~~~~~ ~

Immersed Metals

~of coatings

h

~~~

~

~

INDUSTRIAL AND ENGINEERING CHEMISTRY

January 1948

Hat i.up. Thc rudn u C I C ihcn sanii-bli

mirig IL dopiin (:hat of 10 to 60 niesh in gril

nud a i l nir prcssurc of 72 pounds per square

Xicroscopic measuieinents (450 x ) revealed

t,Iicsc smdhlasted srirfacc.; had maxixiwn

i p s i o n u uf appruximstely 1.5 mils in di

Immcdiately afl,iv sandblasting, t h e rods

sorubbed with 8% dry hand brush t o I C U I O Y ~

nrntrll pmticlt:~of sand from lhc sirface. I3

r:uating, cach d w i wdt. ivas washed in BCC

atxi w c i g h d

I';xcq?t for 1 inch at tlic Aat top end, eacl

IVHS unifwmly cowled by 3 t o 6

applir:at,io:is using IL p ~ s e l <

c l r m d TBLC of fmni 0.021 t o 0.075 inrlr

sceonrl. I)rying t,ook ~ I B C

with

B the ~ o ~ l . t

suspended, hemisphcrieal t.ip down, in

controlled :it. 25" ('. and 40": relative liiinii

t.ha drying time WAS 1 to 2 hours betwen

mat.ing and 48 hours betweeii tho aypliestb

the first mitt and tiic tmt, irnnicision. Tnenty-fuur hours,

t,lie npplicat.iun of ttie la1boai thc rods were given B find W I

ing. T h e average coating t h i

was calculated from

density of the dry film, tho inw

weight due t o the prcr

of tha Iwotecbive film, arid t2ic R ~ coalcd

L

(50.7sq. an,), aa

ing asrnootb s u b t r a t c surface.

At the beginning of tho work it wss found that a e a k spots

o f t e r r obt,ainrd at, the hemispkwrieal t,ip of thc cloctrodes.

led tu prernat,ure failure at t h e x aicm itrid mid;ieading resiit,

values. To eliminaie this difficulty, the hemispherical ti

each clt.ctroiio was given a thick reirrfuorcing dip coating 01

test mnterinl being used, irnmodiafcly after thr final wig1

This reinfomd mea w a s always the litiit t o sliow m y sigr

eodting failure and thedore \*BY not believed to enter si6

cantly into the resistance behavior of the submerged I

Cortsequently, the &ED of the hcmispherieal tip w m elimin

from thc calculatioii of ttrc resiutsnre value8 (ohms for 0110 sq

ceetimeber o f submerged surfme) used in giving results.

For the test irnmemion each coated rod WN-' suhinerged

tieally to a dept,h of 5 cm. (erpmd area = 17.4 sq. cm.

cluding the hemispherical tip) in a I-pi,int Mason jar mntai

..

:

I

I

I

I

0

IO

20

30

.

..-

.

TIME IN OATS

...

...

I

40

50

I

0

0

I

I

I

i

I

IO

20

30

40

50

T l M F IN "A"?

INDUSTRIAL AND ENGINEERING CHEMISTRY

164

300 ml. of natural sea water. This sea water had a pH of 8

and was filtered before use. A No. 30 cork stopper with a hole

for the coated rod and another for the reference electrode bridge

w w used in each jar. The reference half-cell contained Hg,

HgCI, and sea water in t h e flask, and an agar-sea water gel in

the glass tube bridge. This reference half-cell has a constant

potential of +0.299 volt, assuming the volta'ge of the normal

hydrogen electrode t o be zero.

The coated panels used in the test cells of type B were prepared

by members of the New Jersey Zinc Company Research Division

in Palmerton, Pa. This was done so that the results in the

resistance studies on this paint system could be correlated with

osmotic studies performed a t the New Jersey Zinc Company

laboratories with the same coating combination on identically

prepared panels (3). The primer (U. S. Navy specification

52 P 18) was allowed one week of air drying before application

of the low gloss, alkyd hull paint top coat (made from 52 P 25

base). The test exposure was begun two weeks after the application of the top coat.

Two days before the test exposure was started, a glass cylinder

(5 X 1 3 / 4 inches) open a t both ends was attached to the central

portion of each coated panel by use of a rosin-wax mixture applied in the molten state. Each cylinder contained 100 ml. of

test aqueous environment during the exposure period. The

test environments employed were distilled water and aqueous

solutions of 0.780, 2.31, and 3.77% sodium chloride by weight.

Measurements were obtained by using the specimen steel substrate as one electrode and a platinized platinum electrode as the

other.

At the time of measurement, and during the intervals between

measurements, all the test cells were kept in a constant tcmperature room at 25" C. and 40y0 relative humidity. The results

given for any particular test system were obtained in duplicate.

VARIATIONS IN IMETAL SURFACE PREPARATION

Maintenance of good adhesion between the substrate surface

and the applied coating is obviously desirable in obtaining a

durable protective barrier. I n order to effect good adhesion of

the primer coat, the metal substrate is often given an inorganic

surface conversion treatment-for

example, Parkerizing and

Bonderizing-prior t o primer application. The idea was developed in this laboratory that a conversion-type coating which

12 I

I

1

I

Vol. 40, No. 1

contained an organic binder could provide an improved base for

adhesion of the primer. In order to test the practicality of this

idea, a phosphoric acid-zinc chromate-vinyl resin conversion

coating system was formulated. By use of this wash primer

significant increases in adhesion and protective performance were

effected with a number of vinyl resin marine primers for mild

steel in test exposures. As a result, experiments were undertaken to determine whether resistance values could be used to

detect the improvement in protective performance due to the

presence of this wash primer. A representative set of resistance

results is given in Figure 4.

After the first thirty days of sea water immersion this vinyl

resin-red lead primer, coated on untreated sand-blasted mild

steel, displayed a gradual but steady decrease in resistance.

This represented a more progressive decrease in barrier effectiveness than was indicated by the higher and almost constant resistance values obtained during this period when the wash primer

was used. Even though no visible signs of coating failure could

be detected in either case after fifty-six days of immersion, the

differences in resistance became quite pronounced-that is, by a

factor of 1000-as the system without wash primer approached

the resistance region (log R = 6) indicative of the onset of failure.

The validity of this resistance evaluation was confirmed by visual

observation of the test specimens after six months of exposure.

At this latter time the primer applied over the wash primer

showed no signs of failure, whereas in the case of the primer

applied directly over the sahd-blasted mild steel localized rusting

and some film peeling was readily observable.

A consideration of the resistance-time curves given in Figure

4 also suggested that the difference in protective performance

between these vinyl resin-red lead primers, with and without

wash primer, was traceable t o differences in adhesion well before

this could be confirmed in the subsequent visual examination

of the test specimens. A relatively small difference in barrier

effectiveness was indicated from the very high resistance values

obtained with both of these coatings during the f i s t twentyfive days of immersion. This indicated very little difference

during this period in the low rates of transmission of the corrosive materials through the protective systems because of the

presence of the wash primer. In conformity with this indication

a coating of the wash primer alone, like conventional conversion

coatings, v a s seen to offer very little protection (Figure 4).

Therefore, the significant differences in resistance behavior observed after the f i s t thirty days of immersion appeared to depend

upon differences in the ability of the coatings to prevent the

spread of corrosion along the coating-substrate interface. Such

a spreading of corrosion would bring about a gradual loss in

film integrity and lower the observed resistance. For these

reasons this difference in resistance behavior was interpreted

as being due to the difference in adhesion obtained at the

substrate-caating interface by use of the wash primer.

Differences in protective merit due to an improved adhesion

produced by the wash primer treatment were detected by use of

resistance determinations with other vinyl resin marine primer

formulations on sand-blasted mild steel. I n addition, other

experimental results indicated that differences in protective

performance due to other variations in rr-eta1 surface preparation or in the nature of the substrate metal can be predicted

and followed by resistance determinations.

VARIATIONS IN COATING

TIME IN DAYS

Figure 6. Effect of Variations in Pigment

Composition on Protection

3-AMilpolyvinyl butyral primers, sand-blasted mild steel aubstrates, sea water immersion

It is well recognized that, for a given metal surface and a

given aqueous corrosive environment, differences in the binder

composition and in the pigmentation of the coating can lead to

large differences in the protection obtained. I n this section

results are presented which show how the effects on protection

by these and other variations in the coating can be studied and

rapidly determined from resistance values.

After the first twenty days of immersion the gradual decrease in the resistance of the polyvinyl acetate-chloride

k

s

during a six-month exposure.

The results with polyvinyl butyral coatings presented in Figure

6 illustrate how resistance values may be used t o predict differences in protection due to differences in the nature of the

pigment used. The rapid drop in the resistance of the coating

pigmented with titanium dioxide revealed that this coating was

poorly protective. Considerable substrate rusting and coating

blistering could be observed on this specimen after two weeks

of immersion. The unpigmented and red lead-pigmented polyvinyl butyral coatings maintained approximately the same high

resistance values during the fist month of testing. Thereafter,

the higher resistance values obtained with the red lead coating

revealed the improved protection attained through the incorporation of this pikment into the polyvinyl butyral vehicle.

This improvement stands in contrast t o the detrimental effect

obtained when titanium dioxide was used, After four months

of immersion some localized rusting was observed on the specimen containing the unpigmented coating, but no significant signs

of failure could be observed with the red lead coating after a sixmonth exposure.

Another coating variable which is probably of more importance

than is often realized is film thickness. Interest in the use of

thick marine coatings of the hot plastic type prompted resistance

determinations with different thicknesses of a rosin-amorphous

wax coating composition. The results obtained are presented in

Figure 7 as an illustration of how the effect of coating thickness on

protection may be determined from resistance values.

It is seen that the resistance values for this rosin-wax formulation are consistently higher with increasing coating thicknesses.

The visible protective ratings on these specimens after immersion

periods up t o fifteen months have been found to conform with the

relative order of merit which was predicted from the resistance

values obtained during the first two months of immersion.

The initially low resistance values obtained with the 2-mil

coating suggested the presence of discontinuities, or only very

thin protective films, at the peaks of the sand-blasted substrate

surface. This indication and the subsequent rapid decrease in

resistance during the first day heralded early failure. Considerable localized rusting occurred with this specimen during

the second week of testing. Appreciable localized rusting of the

steel could be observed shortly after three months of exposure

exposure. No significant signs of failure could be observed with

the &mil coating of this rosin-wax composition during fifteen

months of immersion.

The specimens used in this latter experiment were carefully

prepared and were not subjected t o any impacts or abrasions

during the test immersion. The coatings were applied by

successive dippings of preheated sand-blasted mild steel rods in

the molten water-white rosin (25y0)-amber amorphous wax

(75%) mixture at 105" C. Immediately after application of the

coatings the specimens were placed in an oven and allowed t o

cool gradually from 90" C. t o 35" C. during a two- t o three-hour

period. Such a technique had to be used t o avoid the formation

of a very thick (50-100 mils), cracked, porous, and poorly adherent coating which is obtained when an ordinary hot dip procedure is used. Therefore, although good protection is indicated

for the 8-mil coating under the experimental conditions used, the

brittleness of the coating and the difficulty of obtaining continuous adherent films of tnis formulation under service conditions

militate against its use in practice.

The results on .the effect of coating thickness indicate that a

coating formulation which gives at least reasonably good protection at the usual test film thicknesses may give a markedly

improved protection at greater film thioknesses. This brings

out the value of applying thicker primer coatings (greater than

3 mils) than are often used in service and the importance of

considering film thickness as a significant variable in obtaining

comparable results in laboratory and field tests. Good protection cannot be expected with a formulation which is known t o be

poorly protective with thin but continuous coatings-for example,

the polyvinyl acetate-zinc tetraoxychromate system (Figure 5)simply by using thicker coatings.

I n Figure 8 the drop in the resistance of a 2-mil copper oxide

antifouling coating, applied directly t o the steel surface, to below

a log R value of 6 during the first ten days is indicative of poor

protection. Since the resistance values for this coating were as

high as log R = 8 during the first two days, a poor water impermeability waa not indicated. The continued decrease of the

resistance indicated the rapid spread of corrosion along the metal

surface, which was probably accelerated b y the presence of

galvanic cells formed by copper being transported in solution

from the pigment t o the metal surface. It ivould be expected,

166

INDUSTRIAL AND ENGINEERING CHEMISTRY

Vol. 40, No, 1

surface of an organic coating may then

be expected to lead to a decrease in the

protective merit. In Figure 9 resistance

values are seen to reveal this effect with

a polyvinyl butyral-zinc tetraoxychromate primer. The curves show conc MIL^ ur UN I iruuLi NU ~ U RI I u

OVER 4 MILS OF PRIMER

sistently lower resistance values for the

!

system in which oxygen was bubbled into

sea water. Localized substrate rusting

became visible shortly after two weeks

of immersion on this latter specimen,

whereas similar signs of failure did not

appear until after four months of exposure with the specimen immersed in

sea R-ater under static atmospheric cona

L

ditions.

These results not only illus84

v)

trate that resistance determinations are

P

reliable in coating evaluations under

these two different environmental cons 2.

ditions but also show how great may

0

20

40

GO

80

100

120

140

160

be the effect of such variations in oxygen concentration on the protection obTIME IN DAYS

tained.

Recent studies by Kittelberger and

Figure 8. Effect of Copper Oxide Antifouling Coating on Protection

Obtained with ZTO Chromate-Polyvinyl Butyral Primer

Elm (3)showed that the water absorption and blistering of a coating combiSand-blasted mild steel substrates, sea water immersion

nation made up of a zinc chromate primer

(Kavy specification 52 P 18) and a

low-gloss gray alkyd top coat (made from 52 P 25 base) applied to

then, that the presence of a suitable thickness of primer would

give an improved bond a t the metal surface and prevent dissolved

mild steel decreased with increased sodium chloride concentracopper from reaching this surface. Under these conditions the

tion in the aqueous environment. In order t o obtain some idea

of the correlation between the results of such studies and coating

antifouling top coat .could serve as an additional barrier in proresistance determinations, identical test panels and envirgntecting the steel. This appears to be the case, since a high resistments were used in resistance studies (Figure 3 B ) . These

ance is maintained longer when 2 mils of the antifouling top

results afforded informatidn regarding the reliability of coating

coat are applied over 4 mils of a zinc tetraoxychromate-polyresistance determinations for studying and rapidly evaluating

vinyl butyral primer than when either the antifouling coat or the

differences in protective behavior due to differences in environpiimer is used alone (Figure 8).

mental salt concentration.

The coating resistance values presented in Figure 8 are in

The curves obtained in these studies during four and one

conformity with the visually observed protective merits of the

coatings after prolonged sea water immersion. With the 2-mil

half months of immersion are given in Figure 10. During this

test period the resistance values are consistently lower, the lower

antifouling coating alone, rusting of the substrate became

the sodium chloride concentration in the aqueous environment.

readily visible after seven weeks of exposure. After seven months

The marked decrease in the resistance values during the first

the 4 m i l primer coating showed some slight localized failure,

five t o eight days corresponds to the rapid diffusion of water into

whereas the 2-mil antifouling coat-4-mil primer coat system has

the films before coating saturation is approached. Thereafter,

given perfect protection for more than two years.

In addition t o the variables discussed in this section, the

effects on protection of other variations in the coating may be

studied by use of resistance values. Experimental results show

that film discontinuity and the effects of variations in coating

drying schedule can be rapidly detected by resistance determinations. Resistance values have also been used in the laboratory

determinations of the highest permissible and optimum pigment

concentration for marine primers. Obviously this technique

STATIC ATMOSPHEFqlC CONDITIONS

10

lends itself to the prediction of the relative merit of commercial

formulations provided the proper service conditions can be approximated in the laboratory testing.

e

VARIATIONS IN AQUEOUS ENVIRONMENT

The third major source of variables which may affect the protective behavior of an underwater coating on a metal is the nature of

the environment. Two of the more important factors in this regard-namely, the concentrations of dissolved oxygen and of salt in

the aqueous environment-have been selected to demonstrate

the validity of resistance values in studies involving differences

in the corrosive environment.

That oxygen is ordinarily an accelerating constituent in the

corrosion of mild steel immersed in sea water is well recognized.

An increase in the concentration of dissolved oxygen a t the

v)

2

K

Figure 9.

4

6

8

IO

TIME IN DAYS

Effect of Environmental Oxygen Concentration on Protection

2.5-Mil coatings of v i n y l resin-ZTO chromate primer, sandblasted mild steel substrates, sea water immersion

January 1948

INDUSTRIAL AND ENGINEERING CHEMISTRY-

167

m

0

20

40

60

80

100

I20

140

160

TIME OF EXPOSURE IN DAYS

Figure 10. Three-Mi1 Coatings Composed of Navy 52 P 18 Primer and Low

Gloss Alkyd Hull Paint

Exposure in aqueous solutions varying i n NaCl concentration, smooth mild steel panel substrates

the almost constant resistance vilues are due to the maintenance

of film integrity. Since the water absorption of this coating has

been shown to increase with decreasing environmental salt concentration (S),$he results given in Figure 10 indicate that during

this test period the dissolution of water by the coating is a more

important factor in determining protective behavior than the

imbibition of environmental salt by the coating.

The prediction of protective merit from the resistance values

obtained during this test period are in agreement with the visual

protective rating of the specimens after extended exposure.

After ten months of immersion the coating exposed to the distilled

water was appreciably blistered, although no substrate rusting

was observed. At this time slight blistering of the coating and a

small amount of substrate rusting were noted with the specimen

exposed to the 0.78% sodium chloride solution. However,*no

signs of coating failure were observed after the ten-month immersion with the coatings exposed to the 2.31% and 3.7’7y0

sodium chloride solutions.

EXTENSION TO OTHER SYSTEMS

A satisfactory cell for determining resistances of coatings on

metal panels which have been immersed in laboratory tanks or in

the field can be set up as follows: With the panel substrate serving ae one electrode, electrolytic connection is made between

the calomel half-cell and the coated surface by placing four to

eight layers of filter paper (for example, 5.5 cm. in diameter),

which have been saturated with sea water, on the coated panel.

The end of the salt bridge is then brought in contact with this

wetted paper, and the method previously described is used to

determine the resistance of the coating under the filter paper.

A modification of this latter technique should also be applicable

to systems exposed t o the afmosphere or in laboratory weathering

units. In this manner a quantitative meashre of protection at

the time of measurement as well as a prediction of relative merits

from the trends of resistance values with time should be possible.

The choice of substrates is limited only to sufficiently conducting materials. Satisfactory work has been carried out in this

laboratory on aluminum (anodized and unanodized), Alclad,

magnesium, and galvanized steel.

resistance behaviors during immersion have always conformed

with the visual protective ratings assigned to the corresponding

test specimens after prolonged laboratory exposure. These

results indicate that the resistance due t o the presence of the

coating is a measure of protection, and that resistance determinations evidently have considerable value in the laboratory evaluation and fundamental study of underwater coatings on metals.

There are variables other than those already studied which,

under practical conditions, may affect protective behavior-for

example, abrasion, erosion, galvanic coupling, radiation, effect of

inhibitors, and chemical deterioration of the coating. However,

there is no reason to believe that these impose any limitation on

resistance values as valid measures of protection. I n so far as

these factors influence the barrier properties of the coating, they

should be reflected in the resistance values obtained. I n fact,

all results show that the resistance values are sufficiently sensitive in this regard to allow a determination of the relative

importance of such variables for a given set of practical conditions.

Therefore, it appears that laboratory resistance values can be

used in the practical rating of underwater coating formulations

for metal surfaces. However, since the protection obtaineq

may differ appreciably with variations in the substrate, the

coating, and the environment, care must be taken to duplicate

closely the proper service conditions in the laboratory testing if

results are to be applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The assistance of V. H: Turkington, L. R. Whiting, and L.

A. Micco (at present with Ansco Laboratories) in this work is

gratefully acknowledged. This work was initiated under a contract between Bakelite Corporation and the Office of Research

and Development, and completed under a contract between

Bakelite Corporation and the Bureau of Ships, Navy Department, which has approved this publication. The opinions presented here are those of the authors and do not necessarily

reflect the official opinion of the Navy Department or the naval

service a t large.

LITERATURE CITED

CONCLUSIONS

e

This resistance technique has been used, to date, in the investigation of over 300 test systems involving coated metals immersed

in aqueous liquids. As is illustrated in this paper, these tests

covered a wide range of the variables which influence the’protection afforded the metal substrate. I n every case good protection was obtained at resistances greater than log R = 8, and

poor protection was obtained a t resistances lower than log R = 6.

In addition, the predictions of coating protectite merit from the

(1) Cherry, R. H.,

Trans. Electrochem. SOC.,72,33 (1937); Sutherlin,

L.,and Cherry, R. H., Ibid., 78,11-20 (1940).

(2) Hayes, W.A.,Proc. I.B.E., t o be published; paper presented

before Inst. of Radio Engrs.,Jan. 26,1944.

ENG.CHEM.,38,695(3) Kittelberger, W.W.,and Elm, A. C., IND.

9 (1946).

(4) Wirth, J. K.,Chem. Fabrik, 11, 455-7 (1938); Korrosion u .

Mstalschutz, 16,69-76, 331-8 (1940); Angewandte Chemie, 54,

369-73 (1941); Korrosion u. Metalschutz, 18,203-9 (1942).

RBCEXVED

May 8 , 1947.

,