Evidence in Management and Organizational Science

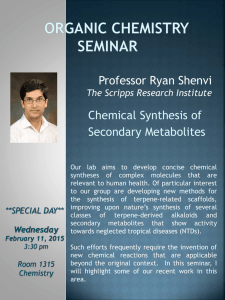

advertisement