Hora est! On dissertations

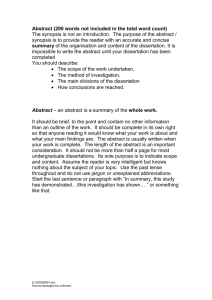

advertisement