Attacking Breach of Implied Warranty Claims in Magnuson

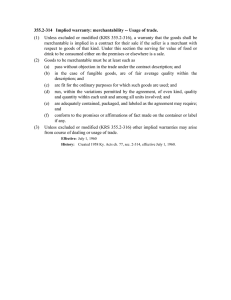

advertisement

Attacking Breach of Implied Warranty Claims in Magnuson-Moss Actions Brought in Privity States Paul E. Wojcicki Kathleen M. McDonough Segal McCambridge Singer & Mahoney, Ltd.* Chicago, Philadelphia, Princeton, Austin, Brighton, New York, Baltimore Introduction In breach of warranty actions brought against motor vehicle manufacturers or distributor/warrantors under the Magnuson-MossBFederal Trade Commission Improvement Act of 1975, 15 U.S.C. ' 2301, et seq. (AMagnuson-Moss Act@), consumers invariably include a breach of the implied warranty of merchantability claim along with their breach of written warranty claim against the remote manufacturer or distributor-warrantor. In theory, at least, a breach of implied warranty claim is easier to prove than is a breach of written warranty claim. Generally, in order to establish a breach of a written warranty, a consumer must show that parts or workmanship in the car proved defective under normal use and were not repaired or replaced under the warranty. Arguably, even if several defects arise, the written warranty is not breached provided that each is repaired or corrected within a reasonable time. On the other hand, to prove a breach of implied warranty of merchantability claim, plaintiff need only show that the vehicle was unfit for its ordinary purpose, that is, it failed to provide a reasonably safe and reliable means of transportation. Accordingly, the warranty may be found to have been breached where there are no recurring problems, but there are a relatively large number of repair attempts during the warranty period. In other words, while a large number of repair attempts, itself, should not be sufficient to impose liability for breach of a written warranty, this factor alone may support a finding that the implied warranty of merchantability has been breached. In Illinois, and several other states, privity is required in order to maintain a cause of action for breach of implied warranty where a plaintiff seeks solely economic damages. That is, the implied warranty arises only between the consumer and his * Mr. Wojcicki and Ms. McDonough are shareholders of the firm. They represent several automobile and motor home manufacturers, importer-distributors, retail dealers, and auto financing companies in Magnuson-Moss actions pending in state and federal courts in Illinois, Indiana, and Michigan. immediate seller, usually the dealer. In the vast majority of cases the consumerplaintiff is not in vertical privity with the manufacturer/warrantor. Federal courts hold that where vertical privity is required to give rise to an implied warranty under state law, it is required under the MagnusonBMoss Act. Federal courts, moreover, reject the notion that by issuing a written warranty, the manufacturer or other warrantor creates privity with the consumer-purchaser. The Illinois Supreme Court has reached the opposite conclusion, reasoning that by giving a written warranty the manufacturer/warrantor creates a Aprivity-like@ relationship between itself and the consumer for purposes of the Magnuson-Moss Act, but not for purposes of state law. But, because MagnusonBMoss is a federal statute, as a matter of policy, state courts should follow federal court decisions construing it. Accordingly, MagnusonBMoss plaintiffs should not be allowed to pursue breach of implied warranty claims in states, like Illinois, that require vertical privity. In Magnuson-Moss Actions, State Law, Including Privity Requirements, Governs the Creation of Implied Warranties The Magnuson-Moss Act defines the term "implied warranty" as "an implied warranty arising under State law . . . in connection with the sale by a supplier of a consumer product." 15 U.S.C. ' 2301(7). Accordingly, under the MagnusonBMoss Act, state law, including privity requirements, governs the creation of implied warranties. Abraham v. Volkswagen of America, Inc., 795 F.2d 238, 249 (2nd Cir. 1986); Walsh v. Ford Motor Co., 588 F.Supp. 1513, 1525 (D.D.C. 1984), affirmed 807 F.2d 1000, 1012 (D.C. Cir.1986); Kowalke v. Bernard Chevrolet, Inc., 2000 WL 656660 (N.D.Ill. Mar. 23, 2000); Jones v. Fleetwood Motor Homes, 1999 WL 999784 (N.D.Ill., Oct 29, 1999); Larry J. Soldinger Associates, Ltd. v. Aston Martin Lagonda of North America, Inc., 1999 WL 756174 (N.D.Ill., Sept. 13, 1999); Feinstein v. Firestone Tire and Rubber Co., 535 F.Supp. 595, 605, n. 13 (S.D.N.Y.1982). If state law requires vertical privity for the creation of an implied warranty, vertical privity is required to maintain a breach of implied warranty claim under MagnusonBMoss. Abraham, 795 F.2d at 242; Walsh, 588 F.Supp. at 1525; Feinstein, 535 F.Supp. at 605, n. 13. In Abraham, owners of Volkswagen Rabbits brought a nationwide class action against Volkswagen under Magnuson-Moss alleging breach of written and implied warranties. Id. 795 F.2d at 241. Volkswagen moved to dismiss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, arguing, inter alia, that plaintiffs could not satisfy the Act=s 100 named-plaintiffs jurisdictional requirement. Id. The district court agreed. It found that breach of implied warranty claims brought under the Act are subject to the privity requirements of the law of the state in which the car was purchased. Id. at 242. Accordingly, the court refused to count the plaintiffs who purchased their vehicles in Illinois, and other vertical privity states, for jurisdictional purposes, finding that those plaintiffs were not in privity with Volkswagen, and thus did not possess a valid implied warranty claim. Id. The Second Circuit affirmed this aspect of the district=s court=s holding, finding that the Act=s Alanguage and legislative history . . . indicate that Congress did not intend to supplant state law with regard to privity in the case of implied warranties.@ Id. at 249 (emphasis added; footnote omitted). Walsh also involved a nationwide class action brought under MagnusonBMoss and alleging claims for, inter alia, breach of the implied warranty of merchantability. Id. 588 F.Supp. at 1517. Ford moved to dismiss the implied warranty claims brought on behalf of the named-plaintiffs who purchased cars in vertical privity states. Id. at 1524. It further argued that plaintiffs who did not possess a valid implied warranty claim could not be counted towards the Act=s 100-named-plaintiff jurisdictional requirement for class actions. Id. The court found that: . . . Congress has specifically provided that implied warranties Aarise@ under State law. 15 U.S.C. ' 2301(7). If, in this action, there are to be any implied warranty claims at all under MagnusonBMoss, they must Aoriginate@ from or Acome into being@ from state law. [Footnote omitted.] Therefore, if a State does not provide for a cause of action for breach of implied warranty where vertical privity is lacking, there cannot be a Federal cause of action for such a breach. Id. at 1525 (emphasis added). The district court further observed that the statutory history and various commentators supported its conclusion that AState privity rules apply when determining the existence of an implied warranty cause of action under MagnusonBMoss.@ Id. For example, a Senate report from the Committee on Commerce, provides: It is not the intent of the Committee to alter in any way the manner in which implied warranties are created under the Uniform Commercial Code. For instance, an implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose which might be created by an installing supplier, is not, in many instances, enforceable by the consumer against the manufacturing supplier. The Committee does not intend to alter existing state law on these subjects. Id., citing Senate Comm. on Commerce, S.Rep. No. 151, 93rd Cong., 1st Sess. 21 (1973) (emphasis added by the court). See also Hearings on Consumer Warranty Protection before the Subcomm. on Commerce & Finance of the House Comm. on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, 93rd Cong., 1st Sess. 91, 94 (March 20, 1973). The Walsh court next turned its attention to the laws of the various states where the vehicles were purchased, including Illinois. It found that in Illinois, vertical privity is required to maintain an action for breach of implied warranty. Id. at 1529. Accordingly, it dismissed the implied warranty claims of the plaintiffs who purchased their vehicles in Illinois since they were not in privity with Ford. Id. at 1530. In Feinstein, plaintiffs in three actions, two of which involved MagnusonBMoss claims, brought claims alleging defects in steel-belted radial tires manufactured by defendant. Plaintiffs moved for certification of a nationwide class. Id. 535 F.Supp. at 597. Among the reasons identified by the district court for denying class certification in the MagnusonBMoss actions was the lack of common questions of law. It found that the Act looks to state law to determine whether an implied warranty is created, and that state implied warranty law differs in many significant areas such as vertical privity requirements. Id. at 605. The court highlighted that, A[i]f state law requires vertical privity to enforce an implied warranty and there is none, then . . . the warranty does not >arise.=@ Id. at 605, n. 13. Illinois and several other states continue to adhere to the vertical privity requirement. See e.g. Rothe v. Maloney Cadillac, Inc., 119 Ill.2d 288, 518 N.E.2d 1028, 1029 (1988) (A[W]ith respect to purely economic loss, the UCC article II implied warranties give a buyer of goods a potential cause of action only against his immediate seller.@); Tomka v. Hoechst Celanese Corp., 528 N.W.2d 103 (Iowa 1995); Auto Owners Ins. Co. v. Chrysler Corp., 129 Mich.App. 38, 341 N.W.2d 223 (1983); Cameron v. American Dental Technologies, Inc., 1995 WL 599871 *6 (E.D.Mich.) (Under Michigan law, Awhere no personal injury is involved, plaintiffs must be in privity with the party against which they are asserting a claim for breach of an implied warranty of merchantability.@); Mt. Holly Ski Area v. U.S. Electrical Motors, 666 F.Supp. 115, 120 (E.D.Mich.1987) (A[I]in order for a plaintiff to recover economic losses on a breach of implied warranty theory under Michigan contract law, privity of contract must exist between the plaintiff and the defendant.@); Davis v. Homasote Co., 281 Or. 383 (1978); see also Henderson v. Chrysler Corp., 191 Mich.App. 337 477 N.W.2d 505 (1991) (privity necessary to maintain a revocation of acceptance claim under the UCC). In the absence of a direct buyer-seller relationship, the implied warranty of merchantability does not arise in the states that require privity. Where the implied warranty does not arise under state law, there exists no implied warranty for a consumer-plaintiff to enforce against the warrantor under the MagnusonBMoss Act. State Court Decisions Holding That Vertical Privity Is Not Required to Maintain an Implied Warranty Claim Under the MagnusonBMoss Act Are Inconsistent with the Federal Decisions And Should Give Way In 1986, the Illinois Supreme Court decided Szajna v. General Motors, 115 Ill. 2d 294, 503 N.E.2d 760, a breach of warranty case brought under the Magnuson-Moss Act and the Illinois UCC. In Szajna, the Court Adecline[d] to abolish the privity requirement in implied-warranty economic-loss cases@ brought under the UCC. Id. 115 Ill.2d at 311, 503 N.E.2d at 767. But, the court further held that as a matter of federal law, where a Magnuson-Moss written warranty is given, the non-privity consumer may also maintain an action for breach of implied warranty against a manufacturer/warrantor. Id. 115 Ill.2d at 315, 503 N.E.2d at 769. Subsequently, in Rothe, the Court explained that in Szajna: We concluded that Magnuson-Moss does more than merely preclude a manufacturer/express warrantor from disclaiming an implied warranty which State law imposes upon him. We concluded that MagnunsonBMoss also actually imposes upon the manufacturer/express warrantor the same implied warranties which, under State law, are imposed only against the buyer=s immediate seller. Rothe, 119 Ill.2d at 209, 518 N.E.2d at 1030. With respect the vertical privity issue, the Supreme Court=s interpretation of MagnusonBMoss is in conflict with the federal court decisions that have addressed the issue, Abraham v. Volkswagen of America, Inc., 795 F.2d 238, 249 (2nd Cir. 1986); Walsh v. Ford Motor Co., 588 F.Supp. 1513, 1525 (D.D.C. 1984); and Feinstein v. Firestone Tire and Rubber Co., 535 F.Supp. 595, 605, n. 13 (S.D.N.Y.1982), as well as the legislative history cited in those cases. Recent federal cases have expressly rejected the Szjana/Rothe analysis of the privity issue. See Kowalke v. Bernard Chevrolet, Inc., 2000 WL 656660 (N.D.Ill. Mar. 23, 2000); Jones v. Fleetwood Motor Homes, 1999 WL 999784 (N.D.Ill., Oct 29, 1999) (NO. 98 C 3061); Larry J. Soldinger Associates, Ltd. v. Aston Martin Lagonda of North America, Inc., 1999 WL 756174 (N.D.Ill., Sept. 13, 1999). The Supreme Court=s decisions in Szajna and Rothe are also inconsistent with its decisions addressing the interpretation of federal law. Recently, in Wilson v. Norfolk & W. Ry. Co., 187 Ill.2d 369, 718 N.E.2d 172 (1999), the court held that Athe decisions of federal courts interpreting a federal statute . . . are controlling upon Illinois courts >in order that the act be given uniform application.=@ Id. 187 Ill.2d at 374, 718 N.E.2d at 175, quoting Busch v. Graphic Color Corp., 169 Ill.2d 325, 332, 662 N.E.2d 397 (1996). It is noteworthy that neither Szajna nor Rothe discuss, distinguish, or even make mention of the Abraham, Walsh, or Feinstein decisions. Accordingly, it is safe to assume, and logical to conclude, that Abraham, Walsh, or Feinstein, in which federal courts interpreted the MagnusonBMoss Warranty Act and its relationship to state law implied warranty claims, were not brought to the court=s attention. Had the Szajna or Rothe courts been aware of Abraham, Walsh, or Feinstein, they would have been required to, and no doubt would have, followed them. The Szajna and Rothe cases are still the law in Illinois. However, a recent trial court decision agreed with the arguments raised here, declined to follow Szajna and Rothe, and dismissed the plaintiff=s breach of implied warranty claim against a distributor-warrantor. A recent unpublished Illinois appellate court decision notes the inconsistency between Szajna=s and Rothe=s analysis of the privity issue and federal decisions which have considered the issue. Griffin v. Mercedes-Benz of North America, Inc. No. 1-99-2580, Order at 22, n. 6 (1st Dist. Aug. 30, 2000). Previously, in Brouillet v. Mitsubishi Motor Sales of America, Inc., the Illinois appellate court, in an unpublished decision, found that the federal court=s analysis of the privity issue Alends further support@ for its decision to affirm the summary judgment entered in favor of the distributor-warrantor on the plaintiff=s breach of implied warranty of merchantability claim. The issue is presently on appeal in two cases pending in the Illinois appellate court, Valenti v. Mitsubishi Motor Sales of America, Inc. and Mitchell-Jackson v. Hyundai Motor America. Conclusion In most cases, a breach of implied warranty of merchantability claim is more difficult to defend than a breach of written warranty claim. Accordingly, obtaining dismissal of an implied warranty claim should make the case easier to defend and increase the likelihood of a defense verdict, or enhance the prospect of a more cost-effective settlement. Under the federal courts= interpretation of the Magnuson-Moss Act, in states that require vertical privity for creation of an implied warranty, a plaintiff is prohibited from maintaining a breach of implied warranty claim against a manufacturer/warrantor with whom he in not in privity. State courts should be encouraged to follow the Illinois Supreme Court=s holding that federal decisions interpreting federal acts, such as Magnuson-Moss, are controlling, and contrary state court decisions should give way to the federal decisions.