The California Working Disabled Program

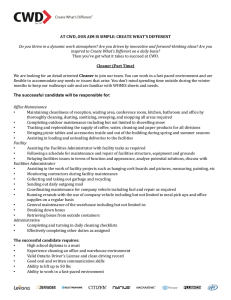

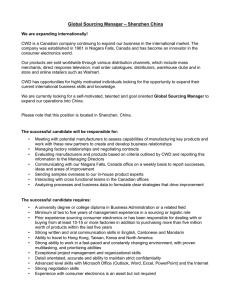

advertisement