A forensic analysis of construction litigation, U.S. Naval Facilities

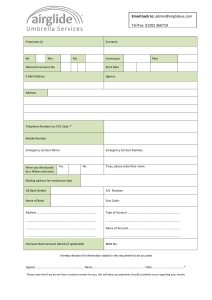

advertisement